Are your bottles cracking during pasteurization or warping during the decoration process? Understanding the thermal physics of your packaging is the difference between a resilient product and a production line disaster.

There is generally an inverse relationship between thermal expansion and the softening point in glass bottles. A "tight" molecular structure that resists expansion (low CTE) typically requires more energy to loosen, resulting in a higher softening point. Conversely, glass with high thermal expansion often has a looser atomic network, leading to a lower softening point.

The Physics of the Glass Network

At FuSenglass, we view glass not as a static solid, but as a frozen network of oxides. The performance of every bottle we manufacture—whether it is a standard soda-lime beer bottle or a high-performance borosilicate vial—is dictated by the strength of the chemical bonds holding this network together. This creates a fundamental link between the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) and the Softening Point.

The CTE measures how much the glass stretches when heated. The Softening Point 1 (technically the "Littleton Point") measures the temperature at which the glass becomes soft enough to deform under its own weight (specifically, when viscosity reaches 10^7.6 Poise).

Think of the glass structure like a suspension bridge.

-

Strong, Rigid Bridge (Low CTE): The cables are tight and made of steel. It doesn’t sway much in the wind (Heat). However, to melt it down or bend it (Softening), you need incredibly high temperatures.

-

Loose, Flexible Bridge (High CTE): The cables are elastic. It stretches easily when heated. Consequently, it also collapses or "softens" at a much lower temperature.

For our clients, this trade-off is critical. If you need a bottle that withstands rapid heating (Thermal Shock), you want a Low CTE. Physics dictates that this bottle will likely be harder to melt and mold, requiring higher furnace temperatures. This is why Borosilicate glass 2 (Low CTE) is more expensive to produce than Soda-Lime glass (High CTE); we have to push our furnaces much harder to reach that higher softening point.

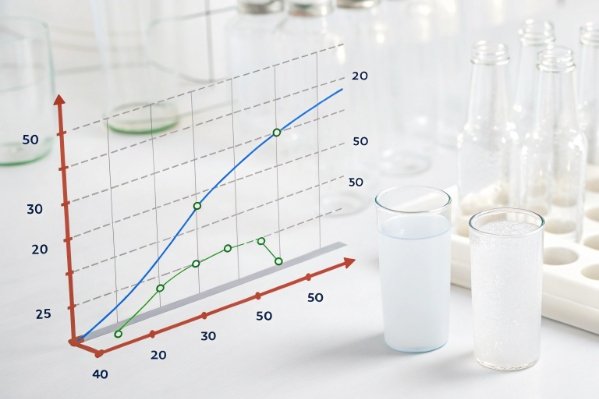

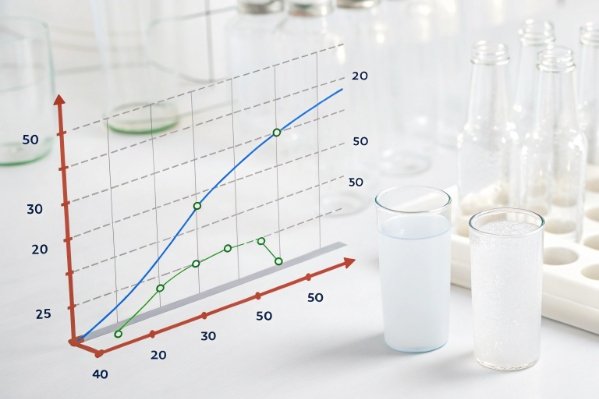

Viscosity-Temperature Relationship

To visualize this, we look at the viscosity curve. Glass doesn’t melt like ice (at a single point); it gradually softens.

| Glass Property | Definition | Typical Soda-Lime Value | Typical Borosilicate Value | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTE (0-300°C) | Expansion per degree Celsius | ~9.0 x 10^-6 /K | ~3.3 x 10^-6 /K | High CTE = Low Softening |

| Softening Point | Temp where glass deforms | ~720°C – 730°C | ~820°C | Low Softening = High CTE |

| Annealing Point | Stress relief temp | ~550°C | ~560°C | Moves with Softening Pt |

| Working Point | Molding temp | ~1050°C | ~1250°C | Harder to process Low CTE |

Do glass compositions with lower CTE usually have higher softening points, and why does that happen?

Why does the glass used for laboratory beakers withstand fire while a wine bottle shatters? The answer lies in the atomic "tightness" of the silica network.

Yes, glass compositions with lower CTE usually have higher softening points because they rely on strong covalent bonds (like Silica and Boron) that resist atomic vibration. These strong bonds prevent the material from expanding when heated (Low CTE) but also require significantly more thermal energy to break apart for flow (High Softening Point).

The "Connectivity" of the Network

The primary reason for this correlation is Network Connectivity.

Glass is made primarily of Silica (SiO2). Silica forms a strong, tetrahedral network.

- Pure Fused Silica: This is the ultimate glass. It is 100% Silica. It has an incredibly low CTE 3 (0.55 x 10^-6/K) because the Si-O bonds are extremely strong. Consequently, its softening point is massive (~1600°C). It is virtually unmeltable in standard furnaces.

To make glass bottles affordable and moldable, we have to "break" this network. We add Fluxes (like Soda Ash – Na2O).

-

The Modifier Effect: The Sodium ions break the strong Si-O-Si bridges and create "non-bridging oxygens." Imagine cutting the steel cables of the bridge and replacing them with rubber bands.

-

Result on CTE: The structure is now looser. When heated, the atoms can vibrate and push apart easily. CTE goes UP.

-

Result on Softening: Because the strong bonds are broken, the glass flows at a much lower temperature. Softening Point goes DOWN.

Therefore, you cannot easily cheat physics. If you want an easy-to-melt bottle (Low Softening), you must accept a high expansion rate (High CTE). If you want a thermally stable bottle (Low CTE), you must accept a difficult-to-melt material (High Softening).

The Boron Anomaly

There is one famous exception we utilize: Boron Oxide (B2O3). In Borosilicate glass, Boron acts as a network former that tightens the structure (lowering CTE) but, at certain concentrations, allows for a reasonable melting point. This is the magic of "Pyrex" style glass—it buys us low expansion without requiring the 1600°C furnace of pure silica.

How do key oxides (SiO2, B2O3, Al2O3, Na2O/K2O, CaO/MgO) shift both CTE and softening behavior in container glass?

Are we chefs or chemists? In the glass factory, we are both, tweaking ingredients to balance meltability with durability.

Key oxides shift behavior by either reinforcing or disrupting the silica network: Network Formers (SiO2, B2O3) and Stabilizers (Al2O3) generally lower CTE and raise the softening point by tightening the molecular structure, while Modifiers (Na2O, K2O) drastically raise CTE and lower the softening point by breaking chemical bonds to aid melting.

The Ingredient Breakdown

When we formulate a batch for a client like Liam (Whiskey) versus JEmma (Serum), we adjust these ratios. Here is how the "Big 5" affect the thermal profile:

1. Silica (SiO2) – The Backbone

-

Role: The main glass former.

-

Effect: Increasing Silica makes the glass "harder" in every way.

-

Shift: CTE ↓ (Down) / Softening Point ↑ (Up).

-

Note: Too much silica, and we can’t melt it.

2. Boron Oxide (B2O3) – The Magic Ingredient

-

Role: Network Former (mostly).

-

Effect: In soda-lime, it acts as a flux. In borosilicate, it tightens the network.

-

Shift: CTE ↓↓↓ (Major Down) / Softening Point ↑ (Moderate Up).

3. Aluminum Oxide (Al2O3) – The Stabilizer

-

Role: Intermediate. It heals breaks in the network.

-

Effect: It makes the glass stiff (viscous). We add it to prevent weathering, but it makes the glass harder to work.

-

Shift: CTE ↓ (Slight Down) / Softening Point ↑↑ (Up).

4. Soda & Potash (Na2O / K2O) – The Fluxes

-

Role: Modifiers. They are the "Solvents" of the glass world.

-

Effect: They create non-bridging oxygens to lower the melting temp. They make the glass "long" (stays soft longer).

-

Shift: CTE ↑↑↑ (Major Up) / Softening Point ↓↓ (Major Down).

-

Warning: High alkali content creates weak glass that shatters easily under thermal shock 4.

5. Lime & Magnesia (CaO / MgO) – The Stabilizers

-

Role: They block the Sodium ions from moving, making the glass chemically durable.

-

Effect: They increase fluidity at high temps but "set" the glass quickly as it cools (Short glass).

-

Shift: CTE ↑ (Moderate Up) / Softening Point ↑ (Up).

| Oxide | Type | CTE Impact | Softening Point Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Former | Lowers | Raises |

| B2O3 | Former | Lowers significantly | Raises (in Boro) |

| Al2O3 | Intermediate | Lowers slightly | Raises (Viscosity builder) |

| Na2O | Flux | Raises massively | Lowers massively |

| CaO | Stabilizer | Raises | Raises |

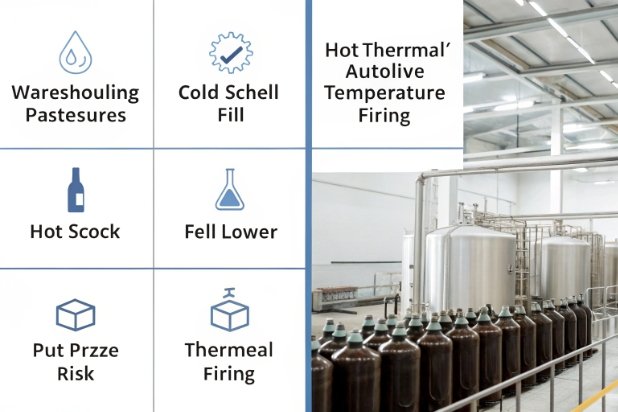

At what temperatures does thermal expansion become a practical risk for bottle deformation in hot-fill, pasteurization, or warehousing?

When does the theory become a broken bottle on your floor? Knowing the failure points protects your inventory.

Thermal expansion becomes a risk for breakage (thermal shock) at temperature differentials (ΔT) of roughly 40°C for soda-lime glass, such as during hot-fill or tunnel pasteurization. However, actual bottle deformation (softening) requires much higher temperatures, typically above 600°C, making it a risk only during secondary decoration processes (decal firing) rather than standard warehousing or filling.

Distinguishing Breakage vs. Deformation

It is crucial to separate CTE Risk (Breakage) from Softening Risk (Deformation).

1. The CTE Risk: Thermal Shock (40°C – 90°C)

This is the daily enemy. Since soda-lime glass has a high CTE, it expands unevenly.

-

Hot Fill: Filling jam at 85°C into a 20°C bottle creates a ΔT of 65°C. Without proper pre-heating, the bottle will snap. The glass isn’t melting; it is tearing itself apart due to rapid expansion.

-

Pasteurization: In a tunnel pasteurizer 5, cold bottles are showered with hot water. If the ramp-up is too fast, the expansion differential causes bottom failure.

-

Note: The "Softening Point" is irrelevant here. The glass is solid. The failure is mechanical stress caused by expansion.

2. The Softening Risk: Decoration Firing (580°C – 620°C)

Warehousing and filling never reach softening temperatures. Your warehouse would have to be on fire (literally) to warp the bottles.

The real risk is Secondary Decoration (Decaling).

-

Scenario: You apply a ceramic decal and bake the bottle to fuse the ink.

-

Risk: The baking temp (approx 600°C) is close to the glass’s transformation range 6. If the bottle is heavy or the glass is "soft" (high sodium), it can Slump.

-

Result: Ovalized necks, sunken shoulders, or warped bases. This is where a lower softening point becomes a liability.

Safe Operating Windows

| Process | Typical Temp | Risk Factor | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warehousing | -10°C to 45°C | None | N/A |

| Cold Filling | 4°C | Thermal Shock (if washed hot) | CTE (Contraction) |

| Pasteurization | 60°C – 70°C | Thermal Shock / Pressure | CTE (Expansion) |

| Hot Fill | 85°C – 95°C | High Thermal Shock | CTE (Expansion) |

| Autoclave | 121°C | Thermal Shock | CTE (Expansion) |

| Decal Firing | 580°C – 620°C | Deformation / Slumping | Softening Point |

What specifications and tests should B2B buyers request to control both CTE and softening performance (dilatometry, viscosity curve, and heat resistance validation)?

Don’t just hope for the best; demand the data. A Certificate of Analysis is your insurance policy.

B2B buyers should request a physical properties report including the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (measured via Dilatometry, ASTM E228) and the Softening Point (measured via Fiber Elongation, ASTM C338). Additionally, for operational safety, request "Thermal Shock Resistance" validation (ASTM C149) to determine the safe temperature differential (ΔT) for your specific filling line.

The Quality Control Toolkit

At FuSenglass, we provide these metrics upon request. Here is what you need to ask for and why:

1. Dilatometry (ASTM E228)

-

What it is: We place a glass rod in a furnace and measure exactly how much it grows as it heats up.

-

The Number: Look for the Mean Linear CTE.

-

Soda-Lime: ~9.0 x 10^-6 /°C.

-

Borosilicate: ~3.3 x 10^-6 /°C.

-

-

Why: This tells you how likely the bottle is to break during hot filling.

2. Softening Point Test (ASTM C338)

-

What it is: We heat a glass fiber until it elongates under its own weight.

-

The Number: Look for Softening Point (°C).

- Standard Flint: ~725°C.

-

Why: Crucial if you plan to do any post-processing like ACL screen printing, decal firing, or metallic sputtering that requires heat.

3. Thermal Shock Simulation (ASTM C149)

-

What it is: This is a "Pass/Fail" destructive test. We heat a basket of bottles in water, then plunge them into cold water.

-

The Number: ΔT (Delta T).

- Standard Requirement: ΔT 42°C.

-

Why: This validates the annealing quality + the glass composition. Even a low-CTE glass will break if it is poorly annealed. This test confirms the bottle can survive your filling line.

Interpreting the Viscosity Curve

Advanced buyers might ask for the full Viscosity Curve 7. This plots the glass behavior from solid to liquid.

-

Strain Point: Limit of serviceability (approx 500°C).

-

Annealing Point: Stress relief (approx 550°C).

-

Softening Point: Deformation (approx 720°C).

-

Working Point: Molding (approx 1050°C).

If you are a decorator, you need to know the Annealing Point. You must fire your decals below this temperature to avoid ruining the temper of the glass or causing deformation.

| Test Name | Standard | Key Metric | Critical For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilatometry | ASTM E228 | CTE (α) | Hot Fill / Pasteurization |

| Fiber Elongation | ASTM C338 | Softening Point | Decal Firing / Decoration |

| Thermal Shock | ASTM C149 8 | ΔT (Max Differential) | Line Efficiency / Breakage |

| Internal Pressure | ASTM C147 9 | Burst Pressure | Carbonated Beverages |

Conclusion

Thermal expansion and softening point are the yin and yang of glass physics. You generally cannot improve one without affecting the other. By understanding that a lower CTE (more stable glass) brings a higher softening point (harder to melt), you can choose the right material—Soda-Lime for cost and shine, Borosilicate for performance—and set the correct specifications to keep your production line running smoothly.

Footnotes

-

The specific temperature at which glass softens enough to deform under its own weight (viscosity 10^7.6 Poise). ↩

-

A glass type with low thermal expansion, used in laboratories for its heat resistance. ↩

-

A measure of how much a material expands when heated, determining its thermal shock resistance. ↩

-

Sudden temperature changes that cause stress and breakage in glass containers. ↩

-

An industrial process for sterilizing bottled products using heat, requiring glass durability. ↩

-

The temperature range where glass transitions from a hard solid to a viscous liquid. ↩

-

A graph showing how glass viscosity changes with temperature, critical for processing limits. ↩

-

Standard test method for thermal shock resistance of glass containers. ↩

-

Standard test method for internal pressure strength of glass containers. ↩