Boiling water feels harmless, but one wrong pour can turn a glass bottle into sharp shards. That risk ruins product, hurts people, and creates returns nobody wants.

It can be safe only when the bottle is designed and tested for hot-fill or thermal shock. For most everyday soda-lime glass 1 bottles, pouring 100°C water into a room-temperature bottle is a cracking risk. Use borosilicate or verified hot-fill containers, and follow controlled warming and filling steps.

Why do “normal” glass bottles crack with boiling water?

Thermal shock 2 is not just “glass hates heat.” The real problem is uneven heat. The inside wall touches 100°C water first. The outside wall stays cooler for a moment. So the inside wants to expand, while the outside resists. That mismatch creates stress. If the stress passes the glass strength at any weak spot, the crack starts.

Thermal shock is a temperature gradient, not a temperature

A bottle can survive 100°C if it warms slowly and evenly. The same bottle can fail at a lower temperature if the change is sudden. This is why “hot water is fine” is not a complete rule. Speed and unevenness decide the outcome.

Bottle weak points that raise risk

Most cracks start at places that already hold stress or damage:

- Thick bases and thick-to-thin transitions

- Seams, embossing, and sharp geometry changes

- Scratches, chips, and small surface flaws

- Poor annealing 3 that leaves high residual stress

What a buyer should focus on

Thermal shock risk is a system problem. Material, shape, process control, packing, and user behavior all matter.

| Risk driver | Why it matters | What to check in a quote |

|---|---|---|

| Glass type | Expansion rate sets how much stress builds | Material spec + test data for thermal shock |

| Wall thickness uniformity | Non-uniform walls create hot/cold spots | Thickness map, base design review |

| Annealing quality | Residual stress 4 makes cracks easier | Polariscope or anneal test requirement |

| Surface condition | Scratches are crack starters | Packaging, handling rules, AQL limits |

| Use case | Real life has repeated cycles | Endurance cycling test, not one-time pass |

When this is framed correctly, “safe” means: the bottle must survive the intended hot contact every time, with an acceptable failure rate. That is a product requirement, not a guess.

What temperature difference between boiling water and the glass typically causes thermal shock cracking?

A bottle can look fine for months, then crack on the first hot pour. That feels random, but it usually comes from one hidden detail: the temperature gap was too large.

For common soda-lime bottles, sudden changes around 40–60°C can start failures, and larger gaps raise risk fast. Borosilicate bottles can handle much larger jumps, often around 150–160°C when certified. Real limits depend on design, stress, and damage.

Rule-of-thumb ranges that match real packaging use

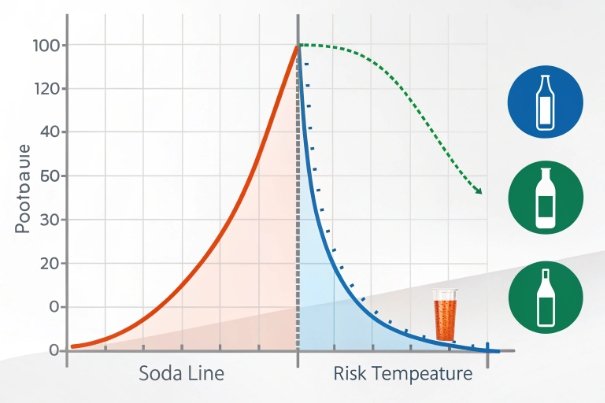

A “typical cracking gap” is not one number. It is a probability curve. Some pieces fail early because of flaws. Better pieces survive more.

- Soda-lime containers (typical beverage bottles): sudden $\Delta T$ in the 40–60°C zone can be risky, especially with thick bases and room-temperature starts.

- Hot-fill jars made from soda-lime: may tolerate higher $\Delta T$, but only when the supplier proves it with thermal shock tests.

- Borosilicate containers: often survive much larger swings. Many lab-style borosilicate bottles are certified around 160°C differential.

Now apply this to boiling water:

- Boiling water is about 100°C.

- A bottle sitting at 20°C has a $\Delta T$ of 80°C at first contact.

That gap is already above the “comfortable” zone for many soda-lime bottles. If the bottle also has a thick base, scratches, or poor annealing, the crack risk becomes real.

A quick decision checklist for buyers and users

| Scenario | Approx. glass start temp | Boiling water $\Delta T$ | Risk level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottle warmed with hot tap | 45°C | 55°C | Lower (still design dependent) |

| Bottle at room temp | 20°C | 80°C | Medium to high for soda-lime |

| Bottle chilled | 5°C | 95°C | High risk for soda-lime |

| Certified borosilicate | 20°C | 80°C | Often acceptable if certified |

Which bottle types are safer for boiling-water contact (borosilicate vs. soda-lime, thick vs. thin wall)?

Picking the wrong bottle type creates a hidden defect in the product experience. The buyer may only see it as “random breakage,” but the root cause is design and material mismatch.

Borosilicate is usually safer for boiling-water contact because it expands less with temperature change. For wall design, uniform and moderately thin walls often handle shock better than thick, uneven sections. Thick bases and sharp transitions raise cracking risk unless proven by testing.

Borosilicate vs soda-lime: what changes in the real world

Borosilicate glass 5 has a much lower thermal expansion 6 rate. That means less stress for the same $\Delta T$. In practice, this gives more margin for user mistakes. It is why lab bottles and heat-safe cookware often use borosilicate.

Soda-lime is the workhorse for packaging. It is cost-effective and strong for normal handling. But it is more sensitive to thermal shock, so hot contact needs more control: better annealing, better design, and better user instructions.

Thick vs thin wall: the counter-intuitive truth

People often assume thick glass is safer. For thermal shock, thick can be worse. The inside heats, the outside stays cool, and the temperature gradient 7 through the thickness is larger. That gradient is the stress driver.

A better rule is:

- Uniform wall thickness is safer than “thick.”

- Avoid thick base pads unless the design is validated for hot fill.

| Bottle choice factor | Safer direction for boiling-water contact | Buyer note |

|---|---|---|

| Glass type | Borosilicate (or proven hot-fill soda-lime) | Ask for certified $\Delta T$ or hot-fill spec |

| Wall thickness | Uniform, not extreme | Demand thickness distribution limits |

| Base design | Less massive, smooth radius | Thick base needs stronger proof |

| Stress level | Low residual stress | Require polariscope checks |

| Surface | Minimal flaws | Packaging and handling spec matter |

What pre-warming steps and filling methods reduce cracking risk when adding boiling water?

Even a good bottle can crack if the filling method creates a shock point. Small process changes often remove most failures.

Reduce cracking by shrinking the temperature gap and slowing the first contact. Pre-warm the bottle gradually, avoid pouring onto the thick base, fill in stages, and keep the bottle off cold surfaces. These steps make heat transfer 8 spread more evenly and reduce stress spikes.

A practical pre-warm routine that works

- Inspect the bottle for chips, scratches, or cracks. Reject damaged pieces.

- Rinse with warm tap water (around 35–45°C). Let it sit for 30–60 seconds.

- Step up the temperature with hotter water if needed (50–60°C), then drain.

- Fill soon after warming so the glass does not cool back down.

The goal is not to “heat the whole bottle to 100°C.” The goal is to reduce the initial $\Delta T$ from 80–95°C down into a safer zone.

Safer pouring and filling methods

| Step | Why it reduces cracking | Simple way to do it |

|---|---|---|

| Warm rinse first | Cuts the $\Delta T$ before first contact | Warm tap water for 30–60 seconds |

| Pour down the side | Avoids heating one point too fast | Funnel + slow pour |

| Stage fill | Lets heat spread before full load | 20% fill, pause, then finish |

| Avoid cold surfaces | Stops the outside from staying too cold | Wood board / silicone mat |

| Delay capping | Reduces internal pressure spike | Cap after a short vent |

What supplier specs and QC tests should be required to confirm boiling-water compatibility for mass orders?

Hot-water compatibility cannot be “trust me.” For large orders, it must be a written requirement, tied to test methods, sampling plans, and acceptance rules.

Require a defined thermal shock rating ($\Delta T$) and a test report using a recognized thermal shock test method. Add QC for annealing stress (polariscope), wall thickness control, and pressure/leak resistance. For mass orders, require both one-time qualification and ongoing lot sampling, with clear pass/fail criteria.

Turn “boiling-water compatible” into a measurable spec

A buyer-side spec should include:

- Intended use case: boiling water contact, hot fill at 85–95°C, wash cycles, or sterilization.

- Thermal shock resistance: minimum $\Delta T$ without failure under a defined method.

- Thermal shock endurance: performance over repeated cycles, not just one event.

- Failure definition: any crack, leakage, or visible fracture counts as failure.

- Sampling plan: how many pieces per lot, and Acceptable Quality Limit 9 (AQL).

How to write the requirement so it is enforceable

| Requirement item | Target (example) | Test / evidence | Lot control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal shock resistance $\Delta T$ | $\ge X^\circ C$ | ASTM C149 10 report | Qualification + periodic audit |

| Thermal shock endurance | Y cycles at $\Delta T$ | Endurance curve or cycle test | Per lot or per shift sampling |

| Residual stress (anneal) | $\le$ limit | Polariscope 11 report | Per lot sampling |

| Internal pressure resistance | $\ge$ limit | Pressure test report | Per lot sampling |

| Thickness variation | within tolerance | Thickness map / gauge record | SPC on forming line |

Conclusion

Pouring boiling water into glass is only safe when the bottle material, design, and QC prove thermal shock resistance, and the filling method reduces sudden temperature gaps.

Footnotes

-

The most common commercial glass, composed primarily of silica, soda, and lime. ↩

-

Stress occurring when different parts of an object expand by different amounts due to temperature. ↩

-

A heat treatment process that alters the physical properties of glass to increase its ductility and reduce hardness. ↩

-

Tension that remains in a solid material after the original cause of the stresses has been removed. ↩

-

A type of glass with silica and boron trioxide, known for having very low coefficients of thermal expansion. ↩

-

The tendency of matter to change its shape, area, volume, and density in response to a change in temperature. ↩

-

A physical quantity that describes in which direction and at what rate the temperature changes the most rapidly around a particular location. ↩

-

The physical act of thermal energy being exchanged between two systems by dissipating heat. ↩

-

A statistical tool used in quality control to determine the maximum number of defective items that can be considered acceptable. ↩

-

Standard test method for thermal shock resistance of glass containers. ↩

-

An optical instrument used to detect internal stresses in glass and other transparent materials. ↩