A bottle can look perfect at room temperature, then crack the moment hot liquid hits it. The silent cause is thermal stress from expansion.

Alumina (Al2O3) usually makes the glass network tighter, and that often pushes the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) lower. The real shift depends on how Al2O3 changes alkali balance, not Al2O3 alone.

Alumina is not “just an additive”, it is a structural decision

Al2O3 sits between “former” and “modifier”

In bottle glass, silica (SiO2) 1 builds most of the network. Alkali oxides 2 help melting, but they also break the network and they usually raise expansion. Alumina is different. Alumina often acts like a network “connector”. It can join the silica network and reduce how easy the structure can move when temperature changes. That is why many glass engineers treat Al2O3 as a lever for durability and stability, not a simple filler.

Why Al2O3 often lowers CTE, but not always

A tighter network tends to expand less. So, a higher Al2O3 level often pushes CTE down. Still, there is a catch. Al2O3 needs charge balance when it enters the network in common glass structures. That balance often comes from alkali ions. If the recipe increases Na2O or K2O to “support” extra Al2O3, the modifiers can push CTE back up. So the direction can be:

-

Down, when Al2O3 rises and alkali stays controlled

-

Flat, when Al2O3 rises but modifiers rise too

-

Up, in some special systems where the recipe trade-offs change bonding and packing in a different way

This is why a buyer should trust measured CTE data more than “Al2O3 is higher” claims.

What this means for bottle sourcing

For wholesalers, Al2O3 is often a sign of how stable the supplier’s recipe is. A very low Al2O3 soda-lime bottle can still work, but it is often less forgiving. A well-designed soda-lime bottle with a sensible Al2O3 level can show better thermal stability, better chemical durability 3, and fewer surprises across batches.

| Composition move | Network effect | Typical CTE direction | Buying takeaway |

|—|—|—|—|

| Raise Al2O3 while holding Na2O/K2O steady | More connected network | Lower | Good for stability and durability |

| Raise Al2O3 and raise Na2O/K2O too | Competing effects | Small change | Demand measured CTE, not promises |

| Replace SiO2 with Al2O3 in a tight recipe | Packing and bonding change | Often lower, sometimes mixed | Confirm with dilatometry data |

| Use high Al2O3 glass families (aluminoborosilicate) | Strong, low-alkali network | Often low | Good for harsh thermal cycles, higher cost |

A lot of bottle failures are not “bad glass”. They are “wrong glass for the process window”. Alumina helps widen that window, but it still needs proof.

If this topic matters, the next sections turn alumina into clear choices for soda-lime, borosilicate, and heat processes.

What does alumina (Al2O3) do to the glass network, and how does that typically shift the CTE?

A spec sheet can say “heat resistant,” then a production run still shows shoulder cracks. That happens when people skip how the network is built.

Al2O3 often increases network connectivity and melt stiffness, and that typically lowers CTE. The shift becomes small or inconsistent when extra alkali is added to balance the added alumina.

How Al2O3 changes the “shape” of the network

The simplest mental model is this: modifiers (like Na2O) create non-bridging oxygens 4 and make the network looser. Alumina tends to do the opposite when it is integrated into the network. It can connect with silica units and increase how many “bridges” exist in the structure. A more connected network usually expands less because the bonds resist movement when heat tries to push atoms apart.

This also changes how the melt behaves in forming. Higher Al2O3 tends to raise viscosity and raise key temperatures. That can help a bottle keep shape during forming, but it can also reduce production flexibility if the plant is not set up for it.

Why the charge-balance detail matters for buyers

When Al2O3 enters the network, it often needs alkali ions nearby for charge balance. That is normal. The risk starts when a supplier uses Al2O3 as a selling point, but they also raise Na2O to keep melting easy. In that case, Al2O3 can improve durability, yet the CTE may not drop much.

So, the practical rule is simple: Al2O3 is a network tool, but Na2O is a network breaker. The final CTE is the result of that push and pull.

A quick checklist for what “good evidence” looks like

-

The supplier states Al2O3 in wt% and gives a tolerance range.

-

The supplier provides measured CTE with a clear temperature interval.

-

The supplier ties chemistry and CTE reports to the same batch or furnace campaign.

| Network question | What Al2O3 tends to do | What can cancel it | What to request |

|—|—|—|—|

| Is the network more connected? | Yes, in most bottle systems | Extra alkali to keep melt easy | Oxide breakdown + CTE test |

| Does the glass expand less? | Often yes | Higher Na2O/K2O | CTE in your process range |

| Is the bottle more forgiving in heat cycles? | Often yes | Poor annealing and thick zones | Strain check + thermal trials |

This is why the best purchasing language is not “high alumina.” The best language is “CTE and chemistry must match, and both must be traceable.”

In soda-lime vs. borosilicate bottles, does higher Al2O3 usually lower or raise thermal expansion?

Some buyers assume borosilicate always means low expansion, and soda-lime always means high expansion. That shortcut causes wrong orders.

In both soda-lime and borosilicate families, higher Al2O3 often lowers expansion when it replaces SiO2 in a controlled recipe. The effect can flatten or reverse if extra alkali is added to balance alumina.

Soda-lime bottles: small Al2O3 changes can matter

Soda-lime container glass 5 usually has a modest Al2O3 level. Even a small shift can change durability and thermal stability. In practical bottle sourcing, Al2O3 often sits in a narrow window because plants optimize for high-speed forming and recycled cullet variation. If Al2O3 rises in a stable way, it often supports a slightly lower CTE and better chemical resistance.

Still, soda-lime has a natural CTE range that is much higher than classic borosilicate 3.3 glass. So alumina tweaks do not “turn soda-lime into borosilicate.” They usually just make soda-lime more stable inside its own category.

Borosilicate bottles: Al2O3 is a stabilizer more than a headline

In borosilicate glass 6, low CTE comes mainly from the broader system design, especially lower alkali and higher silica and boron content. Al2O3 often plays a stabilizing role. It can improve chemical durability, improve resistance to crack growth, and help keep the structure consistent. Some borosilicate systems show better crack resistance as Al2O3 rises, which supports real-world thermal shock behavior 7.

So in borosilicate, Al2O3 can help thermal shock behavior even when the CTE change is not the biggest lever.

The “usually” answer, with the honest caveat

Most of the time, higher Al2O3 pushes toward lower expansion. The caveat is always the same: alkali compensation.

| Bottle family | Common Al2O3 role | Usual CTE impact | Common mistake in sourcing |

|—|—|—|—|

| Soda-lime container | Durability and stability tuning | Slightly lower | Expecting a dramatic CTE drop |

| Borosilicate | Stabilizer for structure and durability | Often small drop or stable | Ignoring that alkali level drives CTE |

| High-alumina special glasses | Low-alkali strong networks | Often low | Assuming all plants can form it fast |

When a buyer asks “Should Al2O3 be higher?”, the best answer is “Only if the supplier can show the measured CTE and keep chemistry consistent across batches.”

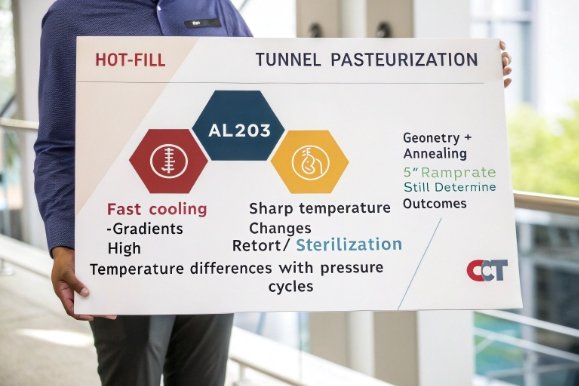

How can Al2O3 levels influence thermal shock resistance for hot-fill, pasteurization, and retort processes?

Heat steps can turn small design flaws into big line losses. A stronger bottle is not always the answer. A more stable bottle often is.

Al2O3 can improve thermal shock resistance by supporting a tighter network and often lowering CTE. It can also raise stiffness, so the net benefit depends on the full thermal stress balance, plus annealing and bottle design.

Hot-fill: alumina helps most when cooling is the real problem

Hot-fill failures often happen during cooling, not during filling. A fast cold rinse can create a big temperature gap across the glass wall. Lower CTE reduces stress for the same temperature gap. So, if Al2O3 helps lower CTE in a soda-lime bottle, it can add margin.

Still, many hot-fill issues come from thick-to-thin transitions at the shoulder, heel, and base. A small CTE improvement will not save a bottle that has sharp thickness jumps and poor annealing. In real projects, a better temperature ramp and a better bottle profile can beat a chemistry change.

Pasteurization: the ramp rate usually wins

Tunnel pasteurization 8 cycles can be long and controlled. If ramps are smooth, soda-lime often works. If ramps are sharp, stress concentrates and cracks appear at weak zones. Alumina helps when it supports stable expansion behavior and good durability, but process control remains the main driver.

Retort: alumina can support stability, but it is not a magic shield

Retort cycles 9 add higher temperatures and pressure effects. Lower CTE is valuable because stress scales with temperature difference. Al2O3 can support low-alkali designs that have better thermal stability. Still, closures, headspace pressure, and liquid movement add extra stress. A retort project should always run full system trials.

| Process | Main thermal risk | How Al2O3 can help | What still decides pass/fail |

|—|—|—|—|

| Hot-fill | Fast cooling gradients | Often lowers CTE, improves stability | Cooling profile, bottle geometry, annealing |

| Pasteurization | Sharp ramp zones | Adds margin against stress | Ramp rate, uniform wall thickness |

| Retort | High ΔT + pressure + cycles | Supports stronger networks and stable chemistry | Retort recipe, closure system, real trials |

A small personal habit has reduced many disputes with buyers: the process profile gets written down before the glass choice gets locked. The bottle should match the heat story, not the marketing label.

What composition limits and verification tests (CTE/dilatometry, XRF chemistry, batch consistency) should wholesalers request before bulk orders?

Many bulk orders fail on paperwork, not on glass. The buyer checks dimensions, but the buyer forgets to lock the thermal and chemistry proof.

Wholesalers should set chemistry tolerances for key oxides like Al2O3 and alkali, then verify with XRF and batch-linked reports. CTE should be verified by dilatometry in the right temperature interval, with clear acceptance limits.

Set composition limits that match your process, not generic tables

For soda-lime bottles, Al2O3 is usually a small part of the recipe, so the tolerance matters more than the headline number. A buyer can request a target range and a tight control window. For borosilicate, Al2O3 is often a stabilizer, so the target range can be set, but the key is still measured CTE and batch consistency.

Practical purchasing language that works:

-

Al2O3 (wt%): target and tolerance range

-

Na2O + K2O (wt%): target and tolerance range

-

SiO2 (wt%): minimum range

-

Batch-to-batch variation limit for each key oxide

Verify chemistry with XRF, and tie it to the same batch as CTE

XRF is fast and widely used for glass oxide verification. A buyer should ask for:

-

Sample prep method (cullet, fused bead, or pressed pellet)

-

Calibration method and reference materials

-

Report showing major oxides and totals

If the first order is large, third-party XRF on random samples is cheap insurance.

Verify CTE with dilatometry using a clear temperature window

CTE is not one fixed value. It depends on the temperature interval used. A hot-fill buyer may care most about room temperature to around 100°C. A retort buyer may care about a wider window. So the report must state:

-

Test method (push-rod dilatometer 10 is common)

-

Temperature interval

-

Number of samples and repeatability

Ask for batch consistency evidence, not only one report

One report can be perfect and still hide drift. A stronger request is:

-

COA for each batch or furnace campaign

-

Control charts or summary statistics for key oxides

-

A statement that recycled cullet control is in place

| Item to request | What it protects | Minimum you want to see | Red flag |

|—|—|—|—|

| XRF chemistry report | Confirms real Al2O3 and alkali | Full oxide list + totals | “Typical only” with no batch ID |

| CTE dilatometry report | Confirms expansion behavior | Method + temperature window | No interval, no repeat tests |

| Batch ID traceability | Links reports to your goods | Batch/furnace/date link | Report cannot be tied to shipment |

| Consistency summary | Detects drift over time | Multi-batch range | Big swings blamed on “normal” |

| Annealing/strain check | Detects residual stress | Polariscopic strain limits | High strain but “CTE is fine” |

For bulk bottle sourcing, the best suppliers do not fear these checks. They already run them for internal control. The buyer just needs them in writing before the container leaves the factory.

Conclusion

Al2O3 often supports lower expansion and better thermal stability, but only stable chemistry and real CTE tests can confirm it for a specific bottle and process.

Footnotes

-

Detailed overview of silica’s role as the primary glass-forming network structural component. ↩

-

How alkali oxides function as modifiers to lower melting temperatures in glass manufacturing. ↩

-

Understanding glass resistance to weathering and chemical attack for long-term storage stability. ↩

-

Explains how these structural disruptions lower the melting point and loosen the glass network. ↩

-

Properties and applications of the most common glass type used for mass-produced containers. ↩

-

Why borosilicate’s low expansion coefficient makes it ideal for high-stress thermal applications. ↩

-

How material composition influences resistance to rapid temperature changes and prevents breakage. ↩

-

Basics of the tunnel pasteurization process and its thermal impact on packaging. ↩

-

Explains the high-temperature sterilization process and stress factors for glass containers. ↩

-

Technical principles of dilatometry for measuring dimensional changes in materials under heat. ↩