Have you ever rejected a batch of glass bottles because the weight data fluctuated wildly, only to find they were perfectly compliant later? Inconsistent weight data disrupts production schedules and erodes trust in suppliers.

No, thermal expansion does not change the mass of a glass bottle; mass is immutable. However, temperature variances between the glass and the environment can cause significant weighing errors due to convection currents, air buoyancy, and scale drift, creating false "out-of-tolerance" data.

The Immutable Physics of Mass vs. The Volatility of Measurement

In the high-stakes world of B2B packaging, "weight" is a contract. A 500g bottle must be 500g, give or take a few grams. When I walk through the Quality Control (QC) labs at FuSenglass, I often see technicians puzzling over digital scales that seem to drift or give inconsistent readings. The first instinct is often to blame the manufacturing process—"The gob feeder is unstable!"—but frequently, the culprit is invisible: Heat.

"Dive Deeper" into the physics, and we recall a fundamental law: The Law of Conservation of Mass. Heating a glass bottle from 20°C to 100°C does not add or remove a single atom of silica. The mass remains absolutely constant. However, the volume changes. The glass expands, the walls get infinitesimally thicker, and the total displacement increases. While the mass of the bottle (Tare Weight) is constant, the conditions under which you measure it are not.

In my 20+ years of experience, I have seen major disputes arise simply because a hot bottle (fresh off the annealing lehr 1) was compared to a cold reference sample. The scale read differently, not because the bottle was lighter, but because the physics of the air around the scale had changed. Understanding the difference between "actual mass" and "measured weight" in a thermal environment is critical for avoiding false rejections.

The Thermal Behavior of Glass Metrics

To manage weight tolerances effectively, we must distinguish between the properties that change with heat and those that remain fixed.

| Property | Behavior Under Heat (Expansion) | Impact on QC Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Mass (Weight) | Constant. Unchanged. | No physical change, but measurement errors occur. |

| Volume (Displacement) | Increases. Glass expands. | Affects fill level height (headspace). |

| Density | Decreases. Volume up, Mass constant. | Irrelevant for standard QC weighing. |

| Brimful Capacity | Increases. Internal volume grows. | Critical for volumetric filling control. |

Now, let’s explore why your scales might be lying to you and how to fix it.

Does glass expansion actually change bottle mass, or just volume?

It is a common misconception on the factory floor that "hot glass is lighter." This is an optical and sensory illusion backed by misinterpreted data.

Glass expansion changes the volume and dimensions of the container, but strictly preserves the mass. However, during hot-fill or heating, the capacity of the bottle increases, which can lead to overfilling if filling by level, affecting the final gross weight of the product, but never the tare weight.

The Physics of Expansion

When we talk about thermal expansion in soda-lime glass, we are talking about a Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) 2 of approximately 9.0 x 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹. This means for every degree of temperature rise, the glass expands.

-

Mass: The amount of material (glass) is determined at the moment the "gob" is sheared and falls into the mold. Once that gob is cut, its mass is set. Heating it up or cooling it down changes nothing.

-

Dimensions: The bottle gets slightly taller and wider.

-

Volume: The internal cavity expands.

The "Fill Weight" Trap

Where brands get confused is in the Gross Weight (Bottle + Liquid).

If you are using a Level Filler (which fills to a specific height, e.g., 60mm from the top):

-

You have a hot bottle (expanded volume).

-

You fill to the standard level.

-

Because the bottle is bigger inside, you have actually poured more liquid into it to reach that level.

-

When you weigh the final product, it is "Overweight."

-

You blame the bottle weight.

In reality, the bottle weight was perfect. The bottle volume change caused you to give away free product. This is why distinguishing between Tare Weight 3 (Glass) and Net Weight (Liquid) is vital.

Expansion Impact Table

Here is how thermal expansion manifests in different measurement contexts.

| Measurement Type | Thermal Effect | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

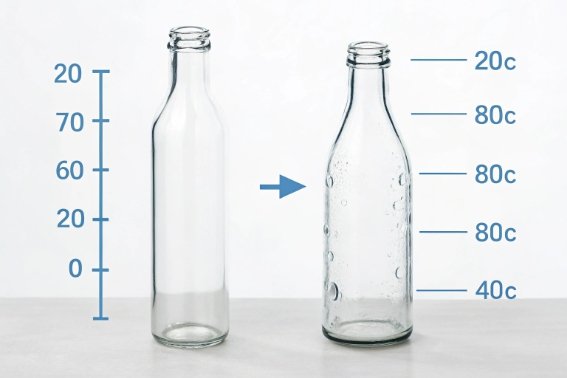

| Tare Weighing | None (Physical). | Mass is identical at 20°C and 80°C. |

| Level Filling | Internal Capacity Increases. | More liquid needed to reach fill line (+Net Weight). |

| Volumetric Filling | None. | Fixed liquid volume -> Lower fill line (looks underfilled). |

| Dimensional Check | Height/Diameter Increases. | potential for false "Out of Spec" on tight tolerances. |

Can temperature differences cause weighing errors that look like “out-of-tolerance”?

If mass is constant, why does a hot bottle weigh less on a precision scale? The answer lies in the air, not the glass.

Yes, temperature differences create "phantom" weight fluctuations. Convection currents from a hot bottle generate lift, making it appear lighter, while condensation on a cold bottle adds water mass, making it appear heavier. These environmental factors cause scale drift and false failures.

The Convection Effect (The "Hot Air Balloon" Error)

When you place a hot bottle (say, 50°C) on a precision analytical balance 4 in a 20°C lab:

-

The bottle heats the air immediately surrounding it.

-

Hot air rises (convection).

-

This rising column of air creates a vertical updraft along the sides of the bottle.

-

This updraft exerts a small lifting force on the weigh pan.

-

Result: The scale reads Lighter than the true weight.

In precision lab scales (4 decimal places), this can look like a significant deviation. Even on industrial check-weighers, strong convection can cause signal instability.

Air Buoyancy

Archimedes’ principle applies to air too. An object is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid (air) it displaces.

-

Hot air is less dense than cold air.

-

If the air density around the scale changes due to the hot bottle, the buoyancy correction factor 5 (internal to many high-end scales) becomes inaccurate.

-

This is usually a micro-gram issue, but for pharmaceutical glass, it matters.

Condensation (The "Sweaty Bottle" Error)

Conversely, bringing a cold bottle (stored in a winter warehouse) into a warm, humid filling room creates condensation.

-

Moisture from the air condenses on the glass surface.

-

Water is heavy. Even a thin film of mist adds grams to the total weight.

-

Result: The scale reads Heavier. You might reject a perfectly light-weighted bottle because it is carrying 2 grams of invisible water.

Measurement Error Matrix

Here is a guide to diagnosing "ghost" weight issues.

| Condition | Physical Phenomenon | Scale Reading Effect | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Bottle / Cold Room | Convection Currents | Lighter (-) | Reading drifts upwards as bottle cools. |

| Hot Bottle / Cold Room | Air Buoyancy Change | Lighter (-) | Minor effect; negligible for heavy glass. |

| Cold Bottle / Humid Room | Condensation | Heavier (+) | Water weight added; visible moisture. |

| Scale Not Warmed Up | Load Cell Drift | Unstable (+/-) | Electronics temp sensitivity. |

How should brands set temperature conditions for tare and net checks?

To stop chasing ghosts, you must standardize the environment. You cannot compare apples to oranges, and you cannot compare hot glass to cold standards.

Brands must establish a strict "Standard Temperature" (typically 20°C – 25°C) for all official tare weight inspections. For net content checks during hot-fill, dynamic tare offsets must be calculated to account for product density changes, rather than blaming bottle mass.

The Rule of Acclimatization

At FuSenglass, we have a "Red Zone" and a "Green Zone" in QC.

-

Red Zone: Hot End measurements. These are for rough guidance only. We know the data is noisy due to heat.

-

Green Zone: The Cold End lab. We do not weigh bottles immediately as they exit the lehr (where they might still be 40-50°C). We allow samples to acclimatize to the lab temperature (23°C) for at least 1 hour. This eliminates convection errors.

Handling Hot-Fill Weight Checks

On your filling line, you cannot wait an hour. You are filling at 90°C.

-

The Fix: You need to calibrate your check-weigher for the process conditions, not the lab conditions.

-

Target Weight Calculation:

$Target = (Bottle Tare{avg}) + (Liquid Volume \times Liquid Density{@90°C})$

Do not use the liquid density 6 at room temperature! Water at 90°C is ~3-4% less dense than at 20°C. If you use the room-temp density to calculate your target weight, you will think the bottle is underfilled or the glass is too light.

Tare Weight Offsets

If you absolutely must weigh hot bottles (e.g., rapid sampling off the line), you must perform a "Correlation Study."

-

Weigh 10 bottles Hot. Record values.

-

Let them cool to room temp. Weigh again.

-

Calculate the average delta (the error caused by convection).

-

Apply this delta as an offset to your scale. (e.g., "Add 0.5g to all hot readings").

Temperature Protocol Checklist

Implement these rules to sanitize your data.

| Check Type | Required Condition | Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Incoming QC (Tare) | Room Temp (20-25°C) | Acclimatize samples 2+ hours before weighing. |

| Line Check (Tare) | Stable Process Temp | Use offset if weighing >10°C diff from ambient. |

| Net Weight (Filling) | Process Temp | Adjust liquid density calc for fill temp. |

| Dispute Resolution | Strict Lab Temp | If supplier/buyer disagree, samples go to 20°C lab. |

What QC practices help control weight compliance across batches?

Consistency in measurement is just as important as consistency in manufacturing. A robust QC protocol eliminates variables so that the only thing you are measuring is the glass.

Effective weight control relies on conditioning samples to ambient temperature, using statistical sampling (like X-bar charts) to spot trends rather than outliers, and strictly following calibration protocols that account for scale warm-up and environmental stability.

Conditioning Samples

Never grab a bottle off a truck parked in the snow and put it on a scale. Never grab a bottle off the annealing lehr and put it on a scale.

- The Protocol: Create a "Staging Area" in your QC lab. All incoming pallets must have samples pulled and left on the rack for a set time (e.g., 4 hours) to reach thermal equilibrium with the room and the scale.

Scale Calibration and Environment

Scales are sensitive instruments.

-

Draft Shields: Ensure all analytical balances have draft shields. Even the HVAC system blowing on a scale can mimic the "convection effect."

-

Warm-Up: Electronic scales need to be turned on for 30-60 minutes before use to stabilize the internal electronics temperature.

-

Daily Check: Use a certified calibration weight 7 (e.g., 500g standard) every morning. If the scale reads 500.05g, zero it.

Statistical Process Control (SPC)

Don’t react to every single bottle. Use SPC.

-

Weigh 5 or 10 bottles every hour.

-

Plot the Average (Mean).

-

Look for trends.

-

Individual bottles might fluctuate due to minor temperature variance or measurement noise.

-

If the Average line shifts, the glass mass is actually changing (mold wear, gob weight change).

-

SPC charts 8 filter out the "thermal noise" and show you the true process capability.

-

Handling "False Failures"

If a batch gets flagged as "Underweight":

-

Stop: Don’t reject yet.

-

Check Temp: Is the batch hot? Is the scale cold?

-

Check Moisture: Is there condensation?

-

Re-Weigh: Allow 10 samples to fully acclimatize for 2 hours and re-weigh. 90% of the time at FuSenglass, the "failure" disappears after acclimatization.

Best Practice Summary Table

Use this table to audit your current QC process.

| Practice | Goal | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Conditioning | Thermal Equilibrium | 2-4 hour wait time before official data entry. |

| Draft Protection | Eliminate Airflow Errors | Use draft shields; move scales away from vents/fans. |

| Calibration | Accuracy | Daily check with certified standard weights. |

| SPC Charting | Trend Analysis | Focus on moving averages, not single data points. |

| Density Correction | Fill Control | Update density values in filler logic based on temp. |

Conclusion

Thermal expansion is a physical reality, but it shouldn’t be a data nightmare. By understanding that mass is constant while volume and weighing conditions fluctuate, you can distinguish between a phantom error and a real defect. Acclimatize your samples, trust your averages, and keep your scales draft-free.

Footnotes

-

A long oven used in glass manufacturing to cool bottles slowly and relieve internal stress. ↩

-

A physical constant that quantifies how much a material expands for every degree of temperature increase. ↩

-

The weight of the empty container, which must be subtracted from the gross weight to find the product weight. ↩

-

A highly sensitive laboratory scale designed to measure mass with extreme precision. ↩

-

An adjustment applied to high-precision weighing to account for the upward force of air displacement. ↩

-

The mass per unit volume of a liquid, which decreases as temperature increases (e.g., hot water is lighter). ↩

-

Standardized weights used to verify and adjust the accuracy of weighing scales. ↩

-

Statistical tools used to monitor process stability and detect non-random variations in manufacturing. ↩