Is your bottling line suffering from mysterious explosions during pasteurization or hot-filling? You might be blaming the glass recipe, but the real culprit is often microscopic damage to the bottle’s skin.

Yes, scratches on glass bottles drastically worsen thermal stress and increase the risk of cracking. Glass is brittle and relies on a pristine surface tension for its strength; a scratch acts as a "stress concentrator" (or Griffith Flaw) that focuses thermal energy into a single point, lowering the bottle’s ability to withstand temperature changes by up to 50%.

The "Pristine Skin" Theory

At FuSenglass, we often remind our clients that glass is theoretically stronger than steel. If you pull on a pristine, untouched fiber of glass, it has immense tensile strength. However, in the real world, we rarely deal with pristine glass. We deal with bottles that have touched molds, conveyor belts, and each other.

The strength of a glass bottle is almost entirely defined by the condition of its surface. Unlike metal, which can deform or stretch to absorb energy, glass is rigid. When a bottle is subjected to Thermal Stress—such as being filled with 90°C jam or plunged into a cold water bath—the glass expands or contracts.

-

Expansion: Puts the outer surface into tension.

-

Contraction: Puts the inner surface into tension.

Glass is incredibly strong in compression (pushing together) but relatively weak in tension (pulling apart). A scratch disrupts the continuous "skin" of the bottle. When the glass tries to stretch during thermal expansion 1, the force doesn’t flow smoothly across the surface. Instead, it gets stuck at the scratch. The scratch acts like a wedge, multiplying the force at its tip. What would have been a manageable stretch for a smooth bottle becomes a catastrophic tear for a scratched one.

The "Griffith Flaw" Concept

In engineering terms, we call these scratches Griffith Flaws 2.

-

Smooth Surface: Stress is distributed over square centimeters.

-

Scratched Surface: Stress is focused onto square micrometers.

Even a scratch invisible to the naked eye can reduce the thermal shock resistance of a bottle from a robust ΔT 60°C down to a fragile ΔT 30°C. For our clients like Liam (Whiskey) or JEmma (Skincare) who might use hot washes or autoclaves, surface integrity is the difference between a successful run and a floor full of broken glass and wasted product.

| Surface Condition | Stress Distribution | Thermal Shock Limit (Approx ΔT) | Failure Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine (Virgin) | Uniform | > 80°C | Very Low |

| Minor Abrasion | Slightly Localized | ~ 50°C – 60°C | Low |

| Deep Scratch | Highly Concentrated | ~ 30°C – 40°C | High |

| Impact Check | Critical Focus | < 20°C | Immediate |

Why do surface scratches act as stress concentrators during hot-fill or rapid temperature changes?

Why does a tiny hairline scratch cause a thick glass base to snap off cleanly? It comes down to the mechanics of leverage at a microscopic scale.

Surface scratches act as stress concentrators because they disrupt the flow of tensile force across the glass surface. Under thermal load, the force lines crowd around the tip of the scratch, multiplying the local stress intensity (K) far beyond the applied load, causing the chemical bonds at the crack tip to unzip and propagate a fracture instantly.

The "Zipper" Effect

Imagine trying to tear a piece of heavy canvas fabric. If you pull on the edges, it is impossible. But if you make a tiny snip with scissors (a scratch) and then pull, it rips effortlessly. The scratch in glass works the same way.

-

Heat: The hot liquid touches the inside glass.

-

Expansion: The inside glass heats up and expands.

-

Tension: The outside glass is still cool. The expanding inside pushes against the outside, putting the outer skin into Tension (stretching it).

If the outer skin is smooth, it resists this stretch. But if there is a vertical scratch, the tension pulls the two sides of the scratch apart.

-

Focus: The energy cannot bridge the gap of the scratch. It dives to the bottom (the tip).

-

Amplification: The stress at the tip can be 10 to 100 times higher than the average stress in the rest of the bottle.

-

Failure: The bonds at the tip snap. The crack travels at the speed of sound. The bottle "bottoms out" (the base falls off).

Orientation Matters

The direction of the scratch matters immensely relative to the stress.

-

Vertical Scratches: Dangerous for internal pressure (carbonation) and hoop stress.

-

Horizontal Scratches: Dangerous for vertical load and thermal shock (which creates axial stress).

For a client filling hot sauce, a horizontal scratch near the base is the deadliest flaw possible. It aligns perfectly with the leverage forces trying to snap the base off during the thermal expansion phase.

Which scratch locations are most dangerous for thermal shock (shoulder, heel, base radius), and why?

Are all scratches equally lethal? No. Geography is destiny when it comes to glass failure.

The most dangerous locations for scratches are the "Heel" (Base Radius) and the "Baffle Line" (bottom seam). This zone experiences the highest tensile stress during thermal shock because it is the junction between the thick, rigid base and the thinner, flexible sidewall, creating a "hinge" point where expansion forces are maximized.

The Critical "Knuckle" of the Bottle

At FuSenglass, we pay obsessive attention to the Heel Radius (the curve where the wall meets the bottom).

During a thermal event (like pasteurization 4):

-

The bottom slab of glass is thick. It heats up slowly.

-

The sidewall is thin. It heats up fast.

-

The Fight: The wall wants to expand; the bottom anchors it back.

-

The Junction: The heel takes the brunt of this fight. It is under maximum shear and tensile stress.

If there is a scratch or an abrasion ring on the heel (common from conveyor belts), the bottle will fail there first.

- The "Smiley Face" Break: A thermal shock break usually looks like a curved crack near the bottom. This is the glass unzipping along the line of maximum stress.

The Shoulder Vulnerability

While the heel is #1 for thermal shock, the Shoulder is #2 for handling shock.

Scratches on the shoulder usually come from bottles rubbing against each other ("shoulder-to-shoulder" contact) on the filling line.

While the shoulder is under less thermal stress than the base, a deep scratch here weakens the bottle against Vertical Load (capping pressure).

-

Scenario: Hot fill (thermal stress) + Capping (mechanical stress) + Shoulder scratch.

-

Result: The neck collapses into the bottle.

| Zone | Stress Type | Failure Mode | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heel (Base Radius) | Thermal Tension | Bottom drops off | Critical |

| Sidewall | Internal Pressure | Vertical Split | High |

| Shoulder | Vertical Load / Impact | Neck Collapse | Medium |

| Neck Finish | Torque / Sealing | Chipped Rim | Medium |

How do abrasion from conveying, packing, and cap application increase breakage under thermal cycling?

Is your production line killing your bottles? "Line abuse" is the invisible erosion of bottle strength.

Abrasion from conveying and packing creates "scuff bands" or networks of micro-scratches that cumulatively weaken the glass surface. Metal-to-glass contact (guide rails) and glass-to-glass contact (accumulation tables) strip away protective coatings and introduce flaws, significantly lowering the bottle’s threshold for surviving thermal cycling.

The "Death by a Thousand Cuts"

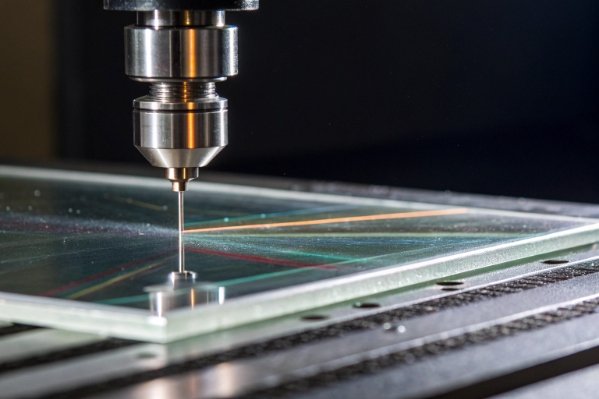

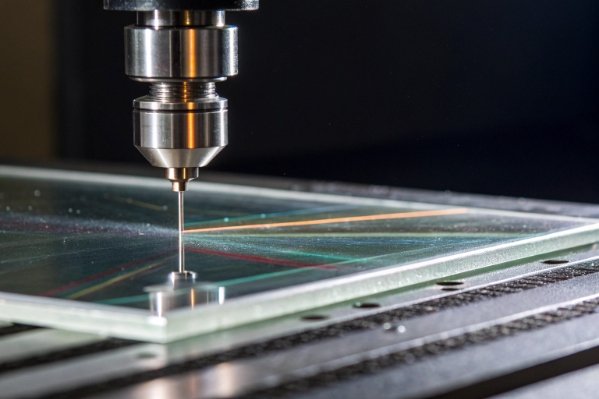

We often analyze broken bottles sent back by clients. We put them under a microscope 5.

We see Scuff Rings. Two distinct bands (one at the shoulder, one at the heel) where the glass looks frosty.

This is where bottles spin against each other on the accumulator table or rub against metal guide rails.

-

Effect: A fresh bottle might withstand a 60°C temperature drop. A "scuffed" bottle might only withstand 35°C.

-

The Mechanism: Abrasion removes the "Cold End Coating" (the lubricant). Once the coating is gone, glass touches glass. Glass is harder than steel. It scratches itself instantly. These micro-abrasions link up to form a continuous weak line around the bottle.

Capping and Handling Damage

The Star Wheel:

If the star wheel (the gear that moves bottles into the filler) is misaligned or worn, it can "nick" the glass. A tiny nick on the body wall becomes the origin point for a thermal crack later in the tunnel pasteurizer.

Gravity Chutes:

In high-speed lines (like beer), bottles slide down chutes. If a nail or screw head is protruding, it scores a vertical line down every single bottle.

- Result: You might fill 10,000 bottles successfully. But when they hit the pasteurizer, 500 of them explode along that score line.

| Source of Abrasion | Location on Bottle | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Accumulation Table | Shoulder & Heel contact | Scuff rings (weakens hoop strength) |

| Metal Guide Rails | Sidewall | Deep scratches (thermal failure) |

| Star Wheels | Body / Neck | Impact checks (cracks) |

| Case Packer | Shoulder | Impact damage |

What prevention and QC steps reduce scratch-related failures (protective coatings, handling design, inspection standards, and thermal shock testing)?

How do you keep the glass pristine in a rough industrial world? It requires a dual strategy of chemical protection and gentle handling.

To reduce scratch-related failures, manufacturers must apply robust "Hot End" (Tin) and "Cold End" (Polyethylene) coatings to lubricate the glass and prevent contact damage. On the filling line, minimize metal-to-glass contact by using plastic (UHMWPE) guide rails, synchronizing conveyor speeds to reduce back-pressure, and implementing strict thermal shock testing (ASTM C149) on incoming ware.

The Coating Defense

At FuSenglass, we don’t ship "naked" glass. We apply two layers of armor:

-

Hot End Coating (Tin Oxide): Applied right after the bottle leaves the mold (at 600°C). It bonds to the glass surface, hardening it.

-

Cold End Coating (Polyethylene/Oleic Acid): Applied after the annealing lehr (at 100°C). This is a lubricant.

-

Function: It makes the glass slippery.

-

Test: We rub two bottles together. They should slide silently. If they "squeak" or "seize," the coating is insufficient, and they will scratch each other.

-

Benefit: A well-coated bottle can slide through a filling line with zero scuffing, preserving its thermal strength.

-

Line Engineering

For our clients setting up new lines, we advise:

-

Soft Handling: Replace steel guide rails with UHMWPE (Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene) plastic. It is softer than glass and won’t scratch it.

-

Minimal Back-Pressure: Adjust conveyor speeds so bottles aren’t grinding against each other with force.

-

Air Cleaning: Use ionized air to clean bottles, not mechanical brushes that can drag grit across the surface.

QC: The Thermal Shock Test

Finally, Testing is Truth.

Every batch we ship undergoes ASTM C149 Thermal Shock Testing.

-

Protocol: We verify the bottles can handle a ΔT of 42°C (standard) or higher (if requested).

-

Abraded Testing: Sometimes we intentionally abrade a sample (simulating line wear) and then thermal shock it. This ensures that even after running through your line, the bottle retains enough strength to survive the pasteurizer.

| Prevention Step | Implementation | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Dual Coatings | Factory Standard | Prevents glass-to-glass friction |

| Plastic Guides | Filling Line Retrofit | Eliminates metal scratches |

| Speed Sync | Conveyor Control | Reduces impact/pressure |

| Thermal Shock QC | ASTM C149 6 Lab Testing | Validates batch resilience |

Conclusion

Scratches are not just cosmetic defects; they are structural wounds that compromise the physics of the container. By treating the glass surface as a critical performance feature—protected by coatings and gentle handling—you ensure that your bottle survives the thermal journey from the kettle to the customer.

Footnotes

-

Technical definition of how materials expand with heat, creating tension in surface defects. ↩

-

Microscopic flaws that drastically lower the fracture strength of brittle materials like glass. ↩

-

A filling method where hot liquid sterilizes the container, creating high thermal expansion stress. ↩

-

A process involving sustained heat and moisture that puts maximum stress on the bottle heel. ↩

-

A tool used to inspect micro-scratches and surface damage invisible to the naked eye. ↩

-

The standard test method for determining the thermal shock resistance of glass containers. ↩