Have you ever opened a shipment of branded glass bottles only to find the logos peeling after filling? It is a production nightmare that damages brand reputation and wastes money.

Yes, thermal expansion can cause peeling. When the glass and the printing ink expand and contract at different rates during temperature changes (CTE mismatch), shear stress builds up at the bonding interface, leading to micro-cracking, flaking, or total delamination of the graphic.

Understanding the Physics of Thermal Stress on Glass Decoration

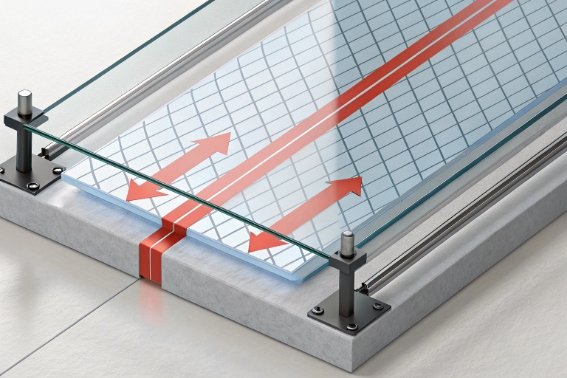

To truly solve the problem of peeling graphics, we must look beyond the glue or the ink itself. We need to look at the physics of materials. Glass, by its nature, is a rigid material with a specific Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) 1. When we apply decoration—whether it is screen printing, decals, or metallic foils—we are adding a second material with a completely different CTE.

In my 20+ years at FuSenglass, I have seen this issue surface most often when brands ignore the thermal lifecycle of their product. The "Dive Deeper" reality is that glass expands when heated and contracts when cooled. While this movement is invisible to the naked eye, it is significant on a molecular level. If the ink layer is rigid and cannot move in sync with the glass, the bond between them is compromised. This is similar to painting a balloon; if the paint is not flexible, it cracks when the balloon stretches. In the glass industry, this "stretch" is caused by heat—hot filling, pasteurization, or even shipping in non-climate-controlled containers.

The Mechanism of Adhesion Failure

When we talk about adhesion failure due to thermal cycling, we are usually discussing shear stress 2. Imagine the glass surface moving to the right while the ink layer wants to expand further to the right. This creates a sliding force parallel to the surface. If this shear stress exceeds the chemical or mechanical bond strength of the ink, the graphic separates. This is why standard adhesion tests performed at room temperature often yield false positives; the print passes when cool, but fails once the bottle undergoes the thermal shock 3 of a bottling line.

Material Compatibility Overview

Below is a breakdown of how different material properties interact during thermal events.

| Material Component | CTE Characteristics | Reaction to Heat | primary Risk Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soda-Lime Glass | Low CTE (~9.0 x 10-6/°C) | Expands slowly and minimally. | Rigid substrate forces stress onto the coating. |

| Organic Inks (Epoxy/UV) | High CTE | Expands rapidly and significantly. | Becomes brittle or too soft, losing grip on glass. |

| Ceramic Inks | Low CTE (Matched to glass) | Expands in sync with glass. | Very low risk; fuses with substrate. |

| Metallic Foils | Moderate CTE | Expands moderately. | Prone to flaking if the adhesive layer degrades. |

Now that we understand the fundamental physics at play, let’s explore which specific decoration methods are most vulnerable so you can make better sourcing decisions.

Which decoration processes are most sensitive to CTE mismatch?

Choosing the wrong decoration method for a hot-fill product is a recipe for disaster. Aesthetics often override technical suitability, leading to expensive failures on the production line.

Organic decoration methods like UV printing, low-temperature decals, and hot stamping are the most sensitive to CTE mismatch. Unlike ceramic materials which fuse to the glass, these rely on surface adhesion and differ significantly in thermal expansion rates from the glass bottle.

The Hierarchy of Thermal Stability

Not all prints are created equal. At FuSenglass, we advise clients based on their filling process. If you are bottling a cold perfume, your options are vast. If you are hot-filling a juice or subjecting a pharmaceutical bottle to autoclaving, your options narrow. The sensitivity to CTE mismatch is largely determined by whether the bond is mechanical (sitting on top) or chemical (fusing within).

Organic vs. Inorganic Decoration

The biggest divide is between organic and inorganic inks. Ceramic Screen Printing and High-Fire Decals use inks made of glass frit (powdered glass) and metal oxides. When these are fired at 600°C or higher, the frit melts and fuses with the bottle surface. essentially, the ink becomes glass. Therefore, the CTE is virtually identical. They expand together and contract together. There is almost zero risk of peeling due to thermal expansion.

The Vulnerability of Surface Coatings

On the other hand, UV Printing, Organic Screen Printing, and Hot Stamping use polymer-based inks or foils. These are plastics and metals sitting on top of silica. Plastics generally expand 10 times more than glass when heated. When a hot-fill process 4 heats the glass, the UV ink tries to expand rapidly. The glass holds it back. This tension snaps the adhesive bond. Furthermore, some UV inks become brittle over time, losing the flexibility needed to absorb this stress.

Decoration Process Sensitivity Matrix

The following table ranks common processes by their risk level regarding thermal expansion.

| Decoration Process | Bond Type | Thermal Sensitivity | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramic Screen Print | Fusion (Chemical) | Very Low | Hot-fill beverages, retort food, heavy reuse. |

| High-Fire Decal | Fusion (Chemical) | Low | Premium spirits, complex art requiring durability. |

| Organic Screen Print | Adhesion (Mechanical) | High | Cosmetic jars, room-temp alcohol, single-use. |

| UV Digital Printing | Adhesion (Chemical) | Very High | Promotional items, short runs, cold-fill only. |

| Hot Stamping | Adhesion (Glue) | Extreme | Luxury cosmetics (avoid for dishwasher safe items). |

How do hot-fill, pasteurization, and rapid cooling create damaging shear stress?

Industrial filling lines are brutal environments for delicate printing. The combination of heat and speed creates physical forces that can rip graphics straight off the glass surface.

Hot-fill and pasteurization cause rapid expansion, while cooling tunnels force rapid contraction. These opposing forces occur in minutes, creating "thermal shock" where the ink layer and glass interface experience maximum shear stress, snapping weak chemical bonds.

The Mechanics of Thermal Shock in Bottling

It is not just high temperature that kills print; it is the rate of change. In a production environment, a glass bottle goes from ambient temperature (20°C) to filling temperature (85-95°C) in seconds. Then, it might enter a pasteurization tunnel 5 where it is held at heat, and finally, it passes through a cooling tunnel to bring it back to room temperature to prevent flavor degradation.

The Expansion-Contraction Cycle

During the Hot-Fill stage, the glass bottle expands. As I mentioned earlier, organic ink attempts to expand much faster. The ink is essentially pulling at its anchors. If the curing was imperfect, the ink might soften at these high temperatures, reducing its internal cohesive strength. It becomes "gummy" and easily displaced by friction on the conveyor belt.

The Danger of Rapid Cooling

The Cooling Tunnel is often where the real damage becomes visible. The bottle surface cools rapidly. The glass contracts. The ink, which might still be hot and expanded, is suddenly forced to shrink. If the ink is a rigid epoxy type, it cannot shrink fast enough. It cracks. If it is a foil, it buckles. This "push-pull" effect weakens the adhesion interface with every degree of temperature change. We often see "micro-cracking" here—tiny fissures that allow moisture to get under the ink. Once moisture enters the interface, the next thermal cycle will pop the print off entirely via steam pressure.

Shear Stress Scenarios in Production

Different stages of the bottling line introduce unique stress vectors.

| Production Stage | Thermal Action | Stress Mechanism on Print | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottle Washing | Hot Caustic Spray | Heat + Chemical Attack | Softens ink resin; surfactant lowers surface tension. |

| Hot Filling | Rapid Heat Spike | Rapid Expansion | Shear stress at edges of the graphic; potential softening. |

| Pasteurization | Sustained Heat | Prolonged Expansion | Creep deformation; ink may slide if contacted. |

| Cooling Tunnel | Rapid Temp Drop | Rapid Contraction | Ink becomes brittle; tensile stress causes cracking. |

What role do surface preparation and curing conditions play in adhesion?

Even the best ink will fail if the glass surface is not properly prepped. Skipping steps here to save time is the number one cause of print delamination in the field.

Surface preparation like flame treatment increases surface energy for better bonding, while proper curing cross-links the ink polymers. Without these, the ink sits passively on the glass rather than gripping it, making it defenseless against thermal movement.

The Critical Importance of Dyne Levels

Glass is naturally hydrophilic, but it can also be non-reactive. For organic inks to stick, the surface energy (measured in Dynes 6) must be higher than the surface tension of the ink. If the glass is "cold" or oily, the ink reticulates—it beads up rather than wetting out. At FuSenglass, we use Flame Treatment or Pyrosil treatment. The flame burns off dust and oils, but more importantly, it deposits functional groups (like hydroxyls) onto the glass surface. These groups act as chemical hooks that the ink can grab onto. Without these hooks, thermal expansion will easily shear the ink off because there is nothing holding it down.

Curing: Locking in the Structure

Applying the ink is only half the battle; curing is where the durability is forged. Whether it is UV curing 7 or thermal curing (baking), the goal is Cross-linking. This turns the liquid monomers into a solid, durable polymer network.

-

Undercuring: The polymer network is loose. The ink is soft and susceptible to chemical attack and thermal softening. It will peel in hot water.

-

Overcuring: The ink becomes extremely brittle. When thermal contraction happens, the ink cannot flex; it shatters like glass.

Environmental Factors in Production

Humidity and ambient temperature in the printing room also play a role. High humidity can interfere with the adhesion promoters in UV inks. If a bottle is printed cold (condensation risk) and then cured, moisture gets trapped under the ink. When that bottle later hits a hot-fill line, that trapped moisture turns to steam and blows the print off the glass.

Preparation and Curing Impact Table

Here is how process variables directly affect the final thermal resistance.

| Process Step | Action | Impact on Thermal Durability | Common Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | Flame / Pyrosil | Increases surface energy (Dyne). | Ink peels in large sheets (Adhesion failure). |

| Ink Mixing | Hardener Ratio | Determines cross-link density. | Ink dissolves or softens in hot water. |

| Curing Time | UV/Heat Exposure | Finalizes polymer structure. | Undercured: Tacky, soft. Overcured: Cracks, flakes. |

| Post-Cure | Resting Period | Allows chemical bonds to settle. | Testing too soon gives false pass/fail data. |

What test protocols should B2B buyers use to validate print durability?

Trusting a supplier’s word is not enough when your brand reputation is at stake. You must rigorously validate print durability using standardized stress tests that mimic real-world conditions.

B2B buyers should demand a testing protocol that includes Thermal Cycling (shock test), the Cross-Hatch Tape Test for adhesion, Dishwasher Resistance testing, and product-specific Chemical Resistance tests to ensure the print survives the product’s lifecycle.

Simulating the Real World in the Lab

At FuSenglass, we do not wait for a customer complaint to find out if a print is durable. We try to destroy it in the lab first. As a buyer, you should mandate these tests in your Quality Assurance agreement. A simple "scratch test" with a fingernail is unprofessional and insufficient for determining how a bottle will react to a 90°C hot fill or a 60°C dishwasher cycle.

The Thermal Cycling Test

This is the most critical test for the issue we are discussing. We take the printed bottle, submerge it in a hot water bath (e.g., 80°C) for a set time, and then immediately transfer it to a cold water bath (e.g., 20°C). We repeat this cycle multiple times. After the cycles are complete, we then perform the tape test. Many prints pass the tape test at room temperature but fail catastrophic after just one thermal cycling test 8. This reveals the CTE mismatch weakness immediately.

Chemical Resistance and Abrasion

Thermal stress often opens the door for chemical attacks. If micro-cracks form due to expansion, the contents of your bottle (alcohol, essential oils, acids) seep in and dissolve the adhesive bond. Therefore, we conduct a "Rub Test" using the actual bulk liquid the bottle will contain. We also use MEK (Methyl Ethyl Ketone) for extreme durability testing, though this is usually reserved for ceramic inks.

Recommended Validation Protocol

Implement this checklist for every new design or new supplier.

| Test Name | Methodology | Standard / Reference | Passing Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Hatch Tape Test | Cut grid pattern, apply tape (3M 610), rip off. | ASTM D3359 9 | 5B Classification (0% area removed). |

| Thermal Shock | Submerge 80°C (10 min) -> 20°C (immediate). | ASTM C149 10 (modified) | No peeling or cracking after tape test. |

| Dishwasher Test | 20+ cycles in industrial dishwasher. | BS EN 12875 | No visual fading or gloss loss. |

| Rub Test (Abrasion) | 50 rubs with alcohol/bulk liquid + 1kg force. | Internal / ISO | No color transfer to the rubbing cloth. |

| Pasteurization Sim | Submerge in 65°C water for 45 mins. | Industry Standard | No blistering or softening of ink. |

Conclusion

Thermal expansion is a silent killer of glass packaging aesthetics. By understanding CTE mismatch, choosing the right decoration method (like ceramic ink for hot-fill), and enforcing strict validation protocols, you safeguard your brand’s premium image.

Footnotes

-

Technical definition of how materials expand with heat and the stress this creates in bonding. ↩

-

The mechanical force that causes sliding separation between layers, leading to adhesion loss. ↩

-

Why sudden temperature changes cause material failure in glass and coatings. ↩

-

Explanation of the hot-fill process and the thermal demands it places on packaging decoration. ↩

-

The mechanics of tunnel pasteurization and its sustained thermal impact on bottle graphics. ↩

-

A unit of measurement for surface tension, critical for ensuring ink adhesion on glass. ↩

-

The process of using ultraviolet light to instantly dry and harden ink polymers. ↩

-

Standard test methodology for evaluating coating resistance to repeated thermal stress cycles. ↩

-

The industry-standard test for assessing adhesion strength using tape and a cross-hatch pattern. ↩

-

The official ASTM method for determining the thermal shock resistance of glass containers. ↩