A coated bottle can look perfect at incoming QC and still fail after one heat cycle. The first sign is often off-flavor, not a visible crack.

Yes. Internal spray coatings can crack, craze, or delaminate when heated, especially when the coating softens, absorbs liquid, or expands differently than the glass. The risk depends on coating chemistry, cure quality, film thickness, and the hot-fill or retort profile.

Why internal coatings crack: expansion mismatch plus wet heat stress

The glass and the coating move at different speeds

Glass expands and contracts with temperature in a smooth, predictable way. A polymer coating does not behave like that. Many internal coatings are viscoelastic. Their stiffness changes fast near the glass transition temperature (Tg) 1. If the process heats the bottle close to Tg, the film can soften and creep. If the process cools the bottle fast, the film can become brittle again while the glass is still contracting. That mismatch creates shear stress at the interface. Shear stress can form craze lines first. It can then turn into real cracking or edge lifting.

Wet heat is a special enemy for internal coatings

Internal coatings face hot liquid, steam, and pressure. Water and acids can diffuse into the film. This can plasticize the coating and lower its effective Tg. It can also weaken adhesion promoters. If the film absorbs liquid, it swells. The glass does not swell. Swelling increases tensile stress in the film and shear stress at the interface. Retort processing 2 makes this worse because temperature and moisture stay high for a long time. Rapid cooling after retort can then lock in damage.

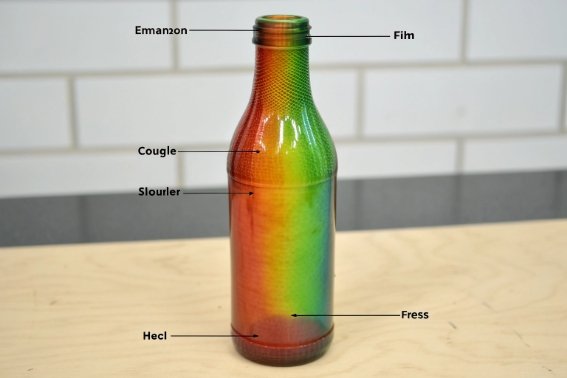

Local stress zones make damage look random

Most coating failures are not uniform. They start at geometry zones where stress concentrates: shoulder, heel, emboss, and base radius. These zones also see uneven heating and cooling. A thick glass area stays hot longer. A thin area cools faster. The coating follows these local gradients. That is why one lot can pass in lab beakers but fail on a real line.

| Stress driver | What it does to the internal coating | Typical visible result | Practical fix that often works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion mismatch (glass vs coating) | builds interface shear during heat/cool | fine crazing lines | adjust cure + choose more flexible resin |

| Wet heat absorption | softens and swells the film | whitening, haze, blisters | pick wet-heat resistant chemistry + lower porosity |

| Rapid cooling | snaps a brittle film under tension | cracking at shoulder/heel | slow first cooling step and reduce ΔT |

| Thick film spots | increase shrink stress and cracking | “map” cracking in patches | tighten thickness window and spray uniformity |

| Weak surface prep | reduces chemical bonding | delamination sheets | stronger cleaning and primer system |

A buyer does not need to fear internal coatings. A buyer needs to treat them like a performance part, not a decoration. The next sections break down which coatings are most sensitive, how processes create stress, and what evidence to request before mass production.

What types of internal coatings are most prone to heat cracking?

A supplier may call every internal lining “food grade.” That label does not predict how it handles a retort cycle or a fast cool-down.

Heat cracking risk is highest for films that are brittle, under-cured, too thick, or sensitive to wet heat. Phenolic-style systems can craze if they are too rigid, some barrier lacquers can blister under wet heat, and sol-gel can micro-crack if the layer is too stiff. Silicone often handles cycling better when applied correctly, but it can fail by poor adhesion or swelling in oils.

Epoxy and epoxy-phenolic systems

Epoxy and epoxy-phenolic coatings are common in food packaging because they can resist acids and protect metal. Inside glass, they are often used as barrier lacquers for aggressive products or to reduce flavor scalping. These systems can be hard and chemically resistant. Still, hardness can become brittleness. If the formulation is rigid, or if the cure is pushed too far, micro-crazing can appear during thermal cycling 3. Wet heat can also weaken the interface if the surface prep is weak.

Silicone and silicone-modified liners

Silicone-based coatings can stay flexible over a wide temperature range. This flexibility can reduce cracking under cycling. That is why silicone is often chosen for heat-resistant applications. Still, silicone can have its own risks. Some silicone films can swell in oils and aromas. Swelling increases stress. Adhesion to glass can also be sensitive to surface energy and primers. A silicone liner can fail by localized delamination rather than classic cracking.

Sol-gel and hybrid inorganic barrier layers

Sol-gel coatings 4 can offer high temperature stability and good barrier properties. They can also be thin and uniform. The main risk is stiffness. Inorganic-like layers can be brittle. If the layer is too thick or too dense, it can micro-crack under strain. Micro-cracks can be hard to see until the product stains them. Sol-gel also needs tight process control because small changes in hydrolysis and cure can change brittleness.

Barrier lacquers (acrylic, polyester, and hybrid systems)

Barrier lacquers vary a lot. Some are flexible and survive cycling well. Some are sensitive to hot water and detergent, so they whiten or blister. Many failures here come from under-cure, solvent entrapment, or weak adhesion. These lacquers often fail first in pasteurization and dishwasher-like wet heat, not in dry heat.

| Coating family | Typical heat-cycling strength | Common weak point | “Most prone” failure in practice | Prevention focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy / epoxy-phenolic | good chemical resistance | can be rigid | crazing lines at stress zones | balance cure and flexibility + tight thickness |

| Silicone | good flexibility | adhesion and swelling | edge lift, local delam | surface prep + primer + oil resistance check |

| Sol-gel / inorganic hybrid | high-temp stable | brittleness if thick | micro-cracks, hairline network | keep layer thin + controlled cure profile |

| Barrier lacquer (organic) | depends on resin | wet heat sensitivity | blistering, whitening, peeling | wet-heat aging + adhesion after soak |

The safest selection rule is simple: pick the coating based on the real process window and the product chemistry. Then qualify it with cycling tests that copy the real line.

How do hot-fill, pasteurization, retort, and rapid cooling create stress that can crack or craze internal coatings?

Many coating problems are created by the cooling step, not by the heating step. The coating sees a full stress story across the whole cycle.

Hot-fill creates inside-out gradients, pasteurization adds long wet heat exposure, retort adds high temperature plus pressure and moisture, and rapid cooling adds a brittle snap-back phase. These stresses can crack or craze internal films when the coating expands, swells, or loses adhesion during the cycle.

Hot-fill: fast gradients and short dwell

Hot-fill processing 5 heats the inner surface first. The coating and the inner glass wall expand. The outer wall lags behind. This creates bending stress through the wall thickness. The coating also sees hot liquid contact. If the liquid contains acids, salts, or oils, the film can soften or swell during the dwell. Then many lines cool the bottle quickly. Some lines use a cold rinse or cold air. Cooling reverses the gradient. The coating contracts while it is still plasticized. The film can then craze as it stiffens during cool-down.

Pasteurization: time and moisture do the damage

Pasteurization 6 often uses warm water spray or steam. The temperature may be lower than retort, but the exposure is long and wet. Wet heat can reduce adhesion by weakening interfacial chemistry. It can also be a blister promoter if the coating contains microvoids or trapped solvent. A coating can look fine right after the tunnel and then show whitening after full cool-down.

Retort: the harsh combination

Retort combines high temperature, high moisture, and pressure changes. Pressure can push liquid into micro-defects. Temperature can move the coating across Tg. Moisture can plasticize the polymer. The interface sees repeated shear. Even a strong coating can craze if the profile is too aggressive. Rapid cooling after retort is a classic trigger for cracking because the glass contracts quickly and the film can become brittle while still under tensile stress.

Rapid cooling: the brittle snap-back phase

Rapid cooling creates the largest ΔT across the wall. It also creates the fastest change in film stiffness. That combination is hard on rigid films. It is also hard on thick films because thick films carry more shrink stress.

| Process step | Main stress on internal coating | Why cracking/crazing happens | Buyer-friendly control lever |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-fill + cap-on | thermal gradient + chemical contact | film expands and softens unevenly | match coating Tg margin + control dwell |

| Pasteurization tunnel | wet heat + long time | adhesion weakens and voids grow | require wet-heat aging before adhesion test |

| Retort hold | high temp + moisture + pressure | swelling + interface shear repeats | choose retort-rated coating and qualify with cycles |

| Rapid cool-down | high ΔT + stiffness jump | brittle snap-back cracks film | specify max cooling rate and minimum cool steps |

A coating rarely fails because it is “bad.” It fails because the cycle is harsher than the coating was built for. This is why buyers should specify the exact thermal story in writing.

What early warning signs indicate internal coating failure?

Internal coating failure can show up before any visible glass damage. Early signals often appear in taste, smell, and appearance.

Early warning signs include fine crazing lines, patchy haze or whitening, blisters, edge lifting near the finish or shoulder, and delamination flakes. Sensory issues like odor or taste transfer can also indicate film breakdown or migration changes.

Visual signs inside the bottle

Crazing often looks like a fine spider-web pattern. It may appear only under angled light. Whitening can appear as cloudy patches. Blisters look like small bubbles under the film. Delamination 7 can look like lifting sheets or flakes. These signs often start at stress zones: shoulder, heel, or near emboss.

A simple tool helps a lot here: a borescope or strong inspection light. A buyer can also use a dye or staining liquid that highlights cracks. Internal defects can hide in clear water but show in colored product.

Functional signs that show up in product performance

When the film cracks, the barrier changes. The product can pick up off-notes. Aroma loss can increase. The product can also interact with the glass surface differently, which can change clarity or create haze in sensitive drinks. If the coating is designed to reduce scalping, coating failure can change flavor stability in storage.

Sensory and contamination signs

Odor or taste transfer can come from partial degradation, under-cure, or extraction changes 8 after thermal cycles. A coating can also shed micro-particles. These may appear as tiny floaters or sediment. That creates consumer complaints even when the bottle stays intact.

| Warning sign | What it usually means | Where it often appears | Fast next step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine crazing lines | film too brittle or overstressed | shoulder and heel | check cure and thickness map |

| Patchy whitening / haze | moisture uptake or microvoid growth | mid-body, high wet exposure | run wet-heat aging + recheck adhesion |

| Blistering | trapped solvent, weak interface, water ingress | near base ring and labels zones | review prep, drying, and cure energy |

| Delamination flakes | adhesion failure | edges, finish, emboss | redo surface prep and primer validation |

| Odor / taste change | extraction shift or incomplete cure | shows in product test | require sensory panel and migration report |

Early warning signs are valuable because they allow a fix before mass returns happen. The key is to link each sign to a controlled test plan.

What validation tests and documents should buyers request?

A coating supplier can claim “retort safe,” but only your protocol can prove it for your bottle, your product, and your line.

Buyers should request thermal shock and thermal cycling tests on finished bottles, adhesion tests before and after wet heat exposure, migration and compliance documents for food contact, and batch traceability that links coating, glass, and process settings to each shipment.

Thermal shock and thermal cycling qualification

The most important rule is that tests must use the finished bottle with the internal coating applied under normal production settings. Lab coupons are not enough. A strong plan includes:

-

a cycle that matches hot-fill or pasteurization steps,

-

a retort simulation when retort is in scope,

-

and a rapid cool-down stress phase if the line uses it.

Pass/fail should include both bottle integrity and coating integrity. A bottle that does not crack can still be a fail if the lining crazes and affects taste.

Adhesion testing that includes wet heat conditioning

Adhesion should be checked:

-

before cycling (baseline),

-

after cycling and cool-down,

-

and after 24 hours conditioning.

Wet heat conditioning matters because many internal coating failures are moisture-driven. If a supplier only shows dry adhesion, the data is incomplete.

Migration compliance and sensory protection

For food contact, buyers should request:

-

a declaration of compliance 9 for the relevant market,

-

migration or extractables test summary for the coating system,

-

and a statement of manufacturing controls (cure conditions, raw material lot control).

Sensory testing is often the fastest “real world” indicator for beverage and sauces. A short storage test after cycling can catch problems early.

Traceability that links reports to shipments

Traceability prevents disputes. The buyer should require:

-

coating batch number,

-

coating application line settings (spray parameters, cure energy),

-

glass furnace campaign ID,

-

and COA that references the same IDs on the packing list.

| Test or document | What it proves | When to require it | Practical pass wording |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal cycling protocol report | coating survives repeated heat/cool | first article + every major change | “No crazing, blistering, or delam” |

| Thermal shock test | margin vs rapid ΔT | hot-fill and rapid cooling lines | “No coating cracks and no glass cracks” |

| Adhesion test (dry + wet aged) | interface stability | every coating batch or campaign | “Adhesion ≥ target after wet aging” |

| Sensory check after cycling | no odor/taste transfer | beverage and aroma-sensitive products | “No detectable off-notes vs control” |

| Migration compliance package | legal food-contact fit | every market and formula change | “Compliance declaration + test summary” |

| Batch traceability + COA | lot-to-lot stability | every shipment | “Batch IDs match COA and packing list” |

A buyer does not need to run every test forever. A buyer needs a strong first qualification, clear retest triggers, and tight traceability 10 so the shipped goods match the tested goods.

Conclusion

Internal spray coatings can crack when heated, mainly from wet heat, expansion mismatch, and rapid cooling. Choose the right lining and lock validation tests, pass criteria, and traceability before mass production.

Footnotes

-

Critical temperature range where a polymer shifts from hard to soft, affecting coating stability. ↩

-

High-temperature sterilization process that creates intense thermal and moisture stress on coatings. ↩

-

Standard test method for assessing coating resistance to repeated heating and cooling cycles. ↩

-

Advanced coating technology using chemical precursors to form thin, durable inorganic layers. ↩

-

Packaging process involving hot liquid fill followed by rapid cooling, creating thermal gradients. ↩

-

Overview of the tunnel pasteurization method and its wet-heat impact on packaging materials. ↩

-

Failure mode where a coating layer separates from the substrate due to adhesion loss. ↩

-

Regulatory details on how substances can migrate from packaging into food products. ↩

-

Legal document confirming that packaging materials meet safety regulations for food contact. ↩

-

System for tracking production lots to ensure quality control and accountability in supply chains. ↩