Many assume glass is chemically inert, but harsh acidic or alkaline environments can silently degrade its structural integrity, leading to unexpected failures.

Yes, acid and alkali corrosion significantly reduce glass bottle strength. Chemical reactions leach ions or dissolve the silica network, creating microscopic surface flaws that act as stress concentrators, drastically lowering impact resistance and burst pressure limits.

Understanding the Hidden Threat to Glass Integrity

While we often think of glass as imperishable, my 20 years at FuSenglass have taught me that it is a dynamic material. The surface of a glass bottle is its first line of defense, and its strength is almost entirely defined by the quality of that surface. When we talk about strength reduction, we aren’t usually talking about the glass wall getting visibly thinner, but rather the microscopic alteration of the surface topography.

In the container glass industry, particularly for our pharmaceutical and chemical clients, understanding this degradation is critical. A bottle that looks perfect to the naked eye might have lost 50% of its strength due to improper washing cycles or storage in aggressive environments.

The process often starts with ion exchange 1 or network dissolution. In simple terms, the chemical bonds that hold the glass together are attacked. For acids, it’s often an exchange of hydrogen ions for alkali ions in the glass. For strong alkalis, it’s a direct attack on the silica-oxygen backbone itself. This doesn’t just make the glass look foggy; it fundamentally alters the tension and compression balance of the surface layer.

At FuSenglass, we emphasize that "strength" is not a static number. It is a function of the flaw population on the surface. Corrosion increases both the number and the severity of these flaws.

Key Differences in Surface Integrity

| Feature | Pristine Glass Surface | Corroded Glass Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Topography | Smooth, continuous silica network | Pitted, porous, or gel-like layer formed |

| Stress Distribution | Uniform compressive stress | Localized stress concentrations 2 at pits |

| Light Transmission | Clear, high gloss | Hazy, iridescent, or "weathered" look |

| Impact Resistance | High (Design specification) | Significantly reduced, unpredictable |

| Chemical Leaching | Minimal / Within USP limits | High release of Sodium/Calcium ions |

Let’s examine exactly how these chemical interactions physically weaken the structure.

How does chemical corrosion create micro-pits and surface flaws that lower impact and burst strength in glass bottles?

Microscopic imperfections turn minor impacts into catastrophic failures by acting as starting points for cracks in the glass matrix.

Chemical corrosion etches the glass surface, removing material unevenly to form "Griffith flaws." These micro-pits concentrate mechanical stress at their tips, meaning a standard impact or internal pressure load becomes sufficient to propagate a crack and shatter the bottle.

The Mechanics of Structural Failure

To understand why a corroded bottle breaks, we have to look at fracture mechanics 3. Glass is a brittle material, meaning it doesn’t stretch or deform plastically before breaking—it just snaps. Its theoretical strength is incredibly high, but its practical strength is determined by its weakest point, usually a surface flaw.

When a glass bottle undergoes chemical attack, the damage is rarely uniform.

- Alkali Attack (The Silica Dissolver): Alkaline solutions (high pH) attack the silica-oxygen ($Si-O-Si$) network directly. This breaks the backbone of the glass structure. The result is often the removal of chunks of the molecular network, leaving behind pits. These pits are not just cosmetic; they have sharp tips at the microscopic level. When the bottle is pressurized (like in a carbonated drink or during filling) or bumped, stress acts like a lever at the tip of these pits, multiplying the force thousands of times.

- Acid Attack (The Ion Exchanger): Acids typically attack by leaching out the modifier ions (like Sodium or Calcium) and replacing them with Hydrogen ions. This creates a silica-rich "gel layer" 4 on the surface. While the network remains intact initially, this porous layer is mechanically weak. As it dries or ages, it can craze and crack, creating a network of fine surface fissures that compromise the underlying pristine glass.

At FuSenglass, we often explain this to clients using the "zipper" analogy. A pristine bottle is a zipped-up coat—strong and unified. Corrosion unzips it slightly at random points. It doesn’t take much force to rip it open the rest of the way.

Impact on Mechanical Properties

| Corrosion Type | Mechanism of Attack | Resulting Flaw Structure | Strength Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali (High pH) | Hydroxyl ions ($OH^-$) break $Si-O$ bonds. | Deep, sharp-tipped pits and general erosion. | Drastic drop in Burst Pressure. Pits act as deep notches. |

| Acid (Low pH) | $H^+$ ions replace $Na^+/Ca^{2+}$ ions. | Porous, hydrated silica gel layer. | Reduced Impact Strength. Surface is fragile and easily scratched. |

| Water (Neutral) | Slow leaching of alkalis (Weathering). | Hazy surface crystals, mild pitting. | Variable. Can weaken bottles during long, humid storage. |

Which corrosion conditions (pH, concentration, temperature, exposure time) most accelerate strength loss and stress cracking risk?

Not all exposure is equal; high temperatures and extreme pH levels act as turbochargers for the chemical reactions that degrade glass.

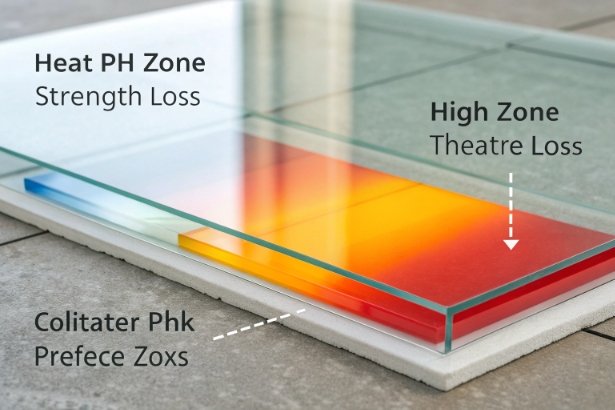

High temperatures combined with extreme pH (especially pH > 9) are the most destructive conditions. Strength loss accelerates exponentially with heat, as every 10°C rise can double the reaction rate, rapidly deepening surface flaws and increasing stress cracking risks.

The Multiplier Effect of Environmental Factors

In our laboratory testing at FuSenglass, we see that corrosion is rarely linear. It follows an Arrhenius relationship 5, where temperature is the dominant accelerator. A cleaning solution that is safe at 20°C might destroy the surface finish and strength of a bottle at 80°C in a fraction of the time.

The pH Factor:

Glass is generally quite resistant to acids (except Hydrofluoric and hot Phosphoric acid). However, resistance drops off a cliff as alkalinity increases. Once the pH exceeds 9.0, the silica network itself begins to dissolve. This is why caustic wash cycles in bottling plants are a major source of strength loss. If a bottle is washed repeatedly in hot caustic soda without proper rinsing or surface protection, it enters the filling line significantly weaker than when it left our factory.

Concentration and Time:

Interestingly, higher concentration doesn’t always mean faster corrosion for acids, but for alkalis, it usually does. "Exposure time" is cumulative. A bottle sitting in a hot warehouse with high humidity can develop "weathering" (a reaction with trapped moisture) over months, which creates alkaline surface condensates that etch the glass over time. This is a silent killer of strength for inventory that sits too long.

We advise our clients to strictly monitor their washing and sterilization parameters. Saving time by increasing temperature often costs them in breakage rates later.

Critical Corrosion Zones

| Condition | Risk Level | Effect on Strength | Common Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH > 10 @ >60°C | CRITICAL | Rapid pitting, massive strength loss (>50%). | Aggressive industrial bottle washing. |

| pH < 4 @ >60°C | MODERATE | Ion leaching, surface weakening. | Acidic product filling (juices, chemicals). |

| pH 7 @ Ambient | LOW | Negligible short-term, "Weathering" long-term. | Standard warehousing/Storage. |

| Thermal Cycling | HIGH | Propagates existing corrosion cracks 6. | Pasteurized products or hot-fill processes. |

How can you test strength after chemical exposure (impact/drop tests, internal pressure tests, residual stress checks) for glass bottles?

Verifying bottle integrity requires destructive mechanical testing and optical analysis to quantify the damage done by chemical attack.

We measure residual strength using Internal Pressure Resistance tests (to check for deep pitting) and Pendulum Impact tests (for surface fragility). Additionally, polarized light inspection helps visualize surface stress changes, ensuring the bottle can still withstand the rigors of the supply chain.

Protocols for Assessing Damage

When a client suspects that a batch of bottles has been compromised by chemical exposure—perhaps due to an improper wash cycle or a reaction with the product—we employ a rigorous testing suite. You cannot rely on visual inspection alone; a bottle can look clean but be mechanically compromised.

1. Internal Pressure Test (Burst Test):

This is the gold standard for detecting deep flaws caused by alkali attack. We fill the bottle with water and pressurize it until it bursts. We compare the "burst pressure" of the exposed bottles against a control group of pristine bottles. A significant drop (e.g., from 30 bar to 15 bar) indicates deep structural pitting.

2. Pendulum Impact Test:

This simulates the knocks and bumps of the production line. A hammer strikes the bottle at the contact points (shoulder and heel). Chemically corroded surfaces have a lower "fracture surface energy," meaning they shatter with much less force. If the impact resistance drops, it suggests the surface "skin" of the glass has been degraded, likely by acid leaching or abrasion.

3. Fractography:

When a bottle does break, we analyze the shards. The fracture origin (the "mirror" zone) tells us exactly where the break started. If the break originated from a tiny pit on the inner surface, we know chemical corrosion was the culprit.

Diagnostic Testing Matrix

| Test Method | Target Flaw Type | What It Reveals | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Pressure (AGR) | Deep Pits / Structural Flaws | Overall loss of tensile strength. | Burst pressure must remain > 75% of design spec. |

| Impact Test (AGR) | Surface Scratching / Haze | Fragility of the outer "skin". | Withstands standard G-force impact without failure. |

| Polariscope | Residual Stress 7 | Changes in annealing tension. | Stress rating remains < Grade 2 (Real Temper). |

| Methylene Blue Dye | Surface Porosity | Absorption of dye into gel layers. | No permanent staining (indicates intact surface). |

What formula, annealing, and surface-protection strategies help maintain glass bottle strength under acid/alkali exposure?

Mitigating corrosion involves enhancing the glass chemistry, ensuring perfect stress relief, and applying protective coatings.

To maintain strength, we utilize Type I Borosilicate glass for maximum chemical resistance, ensure precision annealing to remove internal tension, and apply "Cold End Coatings" (like polyethylene) to lubricate the surface, preventing abrasion from worsening chemical flaws.

Engineering Resilience into Glass

At FuSenglass, we don’t just manufacture bottles; we engineer solutions. Preventing strength loss from corrosion starts long before the bottle is filled. It’s a combination of raw material science and process control.

Glass Formulation (The Chemistry):

For aggressive contents, standard Soda-Lime glass (Type III) may not suffice. We often recommend switching to Type I Borosilicate glass or treating Soda-Lime glass with sulfur (sulfur treatment) to de-alkalize the inner surface. This creates a silica-rich layer that is naturally resistant to further leaching, effectively sealing the glass against attack.

Annealing (The Stress Relief):

Internal tension makes glass vulnerable. If a bottle has residual stress from uneven cooling, chemical corrosion will attack those high-energy areas first, causing "stress corrosion cracking." Our lehrs 8 (annealing ovens) are calibrated to ensure every bottle is virtually stress-free, removing the internal energy that would otherwise help a crack propagate.

Surface Coatings (The Shield):

We apply two layers of coating. The "Hot End Coating" (Tin Oxide 9) acts as a bonding agent. The "Cold End Coating" (Polyethylene or Stearate) provides lubricity. This is crucial because a corroded surface is rough. By making the surface slippery, bottles slide past each other rather than scratching. This prevents the physical widening of the microscopic chemical pits.

Defense Strategy Table

| Strategy | Action | Benefit Against Corrosion | Application Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borosilicate Formula | Add Boron Oxide ($B_2O_3$). | Increases chemical bond strength; resists acid/alkali attack. | Batch Melting |

| Sulfur Treatment | Inject $SO_2$ gas inside bottle. | Extracts surface alkali, leaving a resistant silica skin. | Forming (Hot End) |

| Precision Annealing | Slow, controlled cooling. | Removes residual stress that accelerates cracking. | Annealing Lehr |

| Cold End Coating | Spray Polyethylene wax 10. | Lubricates surface to prevent mechanical propagation of pits. | Cooling / Packing |

Conclusion

Chemical corrosion is not just a cosmetic issue; it is a structural threat that creates microscopic failure points. By controlling storage conditions and choosing the right glass treatment, you can preserve the strength and safety of your packaging.

Footnotes

-

A reversible chemical reaction where an ion from solution is exchanged for a similarly charged ion attached to an immobile solid particle. ↩

-

A location in an object where stress is concentrated, often around holes, notches, or corners. ↩

-

The field of mechanics concerned with the study of the propagation of cracks in materials. ↩

-

A porous form of silicon dioxide made from sodium silicate, used as a desiccant or support for chemical reactions. ↩

-

A formula used to describe the temperature dependence of reaction rates. ↩

-

Cracking induced by the combined influence of tensile stress and a corrosive environment. ↩

-

Stresses that remain in a solid material after the original cause of the stresses has been removed. ↩

-

A long oven used for annealing glass to remove internal stresses. ↩

-

An inorganic compound used as a precursor in the production of glass coatings. ↩

-

A low molecular weight polyethylene used as a lubricant and processing aid. ↩