Shattering bottles during hot filling or pasteurization is a production nightmare that drains profits and damages brand reliability. While glass design plays a role, the fundamental chemical composition of the glass itself is the hidden lever for thermal performance.

Yes, increasing the alumina (Al₂O₃) content generally improves the heat resistance of glass bottles by strengthening the molecular network and lowering the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE). This modification makes the glass more resistant to the rapid temperature changes that cause thermal shock.

The Role of Alumina in Glass Chemistry

At FuSenglass, we often have to explain to procurement teams that "glass" is not a single, static material. It is a formulation. Standard soda-lime glass, which makes up the vast majority of container glass, typically contains 1.5% to 2.5% aluminum oxide 1 (Al₂O₃). However, when a client comes to us with a project requiring high thermal endurance—such as for pharmaceutical vials or premium hot-filled beverages—we look closely at this specific oxide.

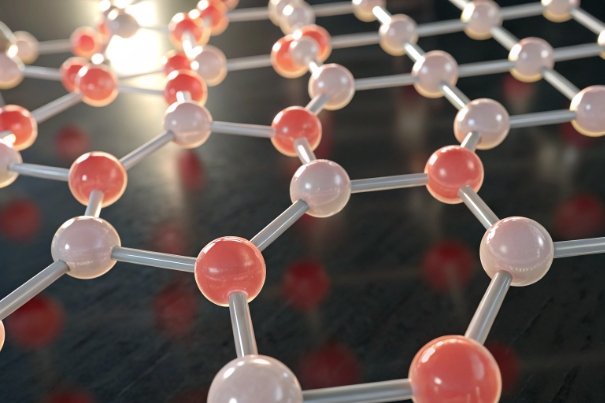

Alumina acts as a "network intermediate" in the glass structure. Unlike silica 2 (SiO₂), which forms the backbone, and soda ash 3 (Na₂O), which softens the glass to make it meltable, alumina bridges the gap. It stabilizes the network. By replacing some of the alkali ions or simply tightening the silica bonds, Al₂O₃ increases the glass’s viscosity and mechanical strength.

Most importantly for thermal applications, Al₂O₃ helps to lower the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE). The CTE is the measure of how much the glass expands when heated. High expansion leads to high stress during temperature changes. By lowering the expansion rate, we reduce the internal stress generated during hot filling or autoclaving 4, effectively raising the thermal shock threshold.

Comparison of Glass Types

To understand the magnitude of the difference, we can compare standard bottle glass with high-alumina variants. While true borosilicate glass (like Pyrex) uses boron to achieve heat resistance, increasing alumina in soda-lime glass is a more cost-effective way to bridge the gap for industrial packaging.

| Glass Composition Type | Typical Al₂O₃ Content | CTE (x 10⁻⁷/°C) | Thermal Shock Limit (ΔT) | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Soda-Lime | 1.5% – 2.0% | ~90 | ~42°C | Water, Juice, Spirits |

| High-Alumina Soda-Lime | 2.5% – 4.0% | ~85 | ~50°C – 55°C | Premium Hot-Fill, Pharma |

| Aluminosilicate | 15% – 20% | ~40 – 50 | >120°C | Chemical Labware, LCD Screens |

| Neutral Borosilicate (5.0) | 5% – 7% | ~50 | >150°C | Injectable Vials, Ampoules |

As you can see, shifting the alumina content slightly in a soda-lime recipe can yield a measurable improvement in thermal shock resistance without the extreme cost of switching to borosilicate.

However, chemistry is a game of balances. You cannot simply dump more alumina into the furnace without consequences. Let’s explore how this structural change works and what it costs in terms of production.

How does adding Al₂O₃ change glass structure and thermal shock resistance in bottle applications?

Standard glass formulations often prioritize meltability over durability, leaving bottles vulnerable to sudden thermal spikes on modern high-speed lines. Strengthening the atomic framework is the only way to fundamentally alter this physical limitation.

Adding Al₂O₃ creates a tighter, more interconnected silicate network, significantly increasing chemical durability and reducing atomic mobility. This structural rigidity lowers the thermal expansion rate, directly boosting the bottle’s ability to withstand sudden temperature gradients without fracturing.

The Network Intermediate Mechanism

In a standard soda-lime glass mixture, Sodium Oxide (Na₂O) acts as a flux—it breaks up the continuous Silicon-Oxygen (Si-O) network to lower the melting temperature. While this makes manufacturing cheaper, it creates "non-bridging oxygens" which are weak points in the structure. This "loose" structure expands significantly when heated.

When we introduce Alumina (Al₂O₃), it enters the glass network and consumes these non-bridging oxygens. It re-links the broken chains. The aluminum ion (Al³⁺) essentially repairs the interruptions caused by the sodium. This results in a "polymerized" or more connected network.

Impact on Thermal Shock Resistance

The physics of thermal shock 5 breakage is defined by the stress generated when the surface expands while the core remains cool. The formula for thermal stress 6 ($\sigma$) is roughly proportional to the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion ($\alpha$).

$$ \text{Stress} \propto \text{Young’s Modulus} \times \text{Expansion Coefficient} \times \Delta T $$

By adding alumina, we slightly increase the Young’s Modulus 7 (stiffness), but we decrease the Expansion Coefficient more significantly. The net result is a glass that expands less for the same amount of heat. Less expansion means less differential stress between the hot surface and the cold interior.

For our clients, this means a bottle that might normally crack at a ΔT (temperature difference) of 42°C might now survive a ΔT of 50°C or 55°C. This safety margin is critical for "Hot Fill and Hold" processes where the liquid is introduced at 85°C–90°C.

Chemical Durability Bonus

There is a secondary benefit: Chemical Resistance. High-alumina glass is far more resistant to water (hydrolytic resistance) and alkali attack. This is why pharmaceutical bottles (Type II glass) are often treated soda-lime or high-alumina formulations—to prevent the glass from leaching into the medicine during sterilization (autoclaving).

| Structural Feature | Effect of Low Alumina | Effect of High Alumina | Impact on Bottle Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Connectivity | Loose, many non-bridging oxygens. | Tight, re-polymerized network. | High Alumina = Stronger glass matrix. |

| Alkali Mobility | High (Na+ moves easily). | Low (Na+ locked in place). | High Alumina = Better chemical stability. |

| Thermal Expansion | High (expands rapidly). | Reduced (expands moderately). | High Alumina = Less thermal stress. |

| Viscosity Curve | steep (sets quickly). | Stiff (sets slowly). | High Alumina = Harder to form. |

What trade-offs can Al₂O₃ bring to bottle making?

While alumina enhances performance, it wreaks havoc on standard furnace operations if not managed with precision. Ignoring the production difficulties leads to defects, unmelted stones, and skyrocketing fuel costs.

High Al₂O₃ content significantly increases the viscosity and melting temperature of the glass, requiring more energy and higher furnace temperatures. It also raises the risk of "stones" (devitrification) and cords (streaks) if the batch is not mixed and melted perfectly, potentially compromising clarity and production speed.

The Melting Point Penalty

Alumina is refractory—it resists heat. It is the same material used to make firebricks that line the furnace! Therefore, trying to melt it into the glass is difficult. Increasing Al₂O₃ from 1.5% to 3.0% requires the furnace temperature to be raised, often by 20°C to 50°C. This drastically increases fuel consumption (natural gas or electricity).

For a high-volume factory like FuSenglass, energy is a major cost driver. A recipe change that increases fuel usage by 10% translates directly to a higher unit price for the client.

Viscosity and Fining Issues

High-alumina glass is "stiff." Its viscosity 8 remains high even at melting temperatures.

-

Bubble Removal (Fining): In standard glass, bubbles rise to the surface and escape. In stiff, high-alumina glass, bubbles get trapped. This can lead to "seeds" or "blisters" in the final bottle, which are cosmetic defects.

-

Homogeneity: If the alumina raw material (usually feldspar 9 or nepheline syenite) doesn’t mix perfectly, it forms "cords"—visible wavy lines in the glass. These cords have a different refractive index 10 and, ironically, a different expansion coefficient, which can actually cause the bottle to break spontaneously.

Devitrification Risks

Glass is a supercooled liquid; it wants to be a crystal. If held at certain temperatures, it will try to crystallize (devitrify). High alumina levels can alter the "liquidus temperature," making the glass more prone to forming crystals (stones) during the forming process if the temperature drops too low in the feeder. These stones are fatal defects that act as stress concentrators.

Cost Implications

Beyond energy, the raw material itself is more expensive. High-quality alumina sources (low iron) are needed to maintain clarity. Using cheap alumina sources often brings in Iron (Fe), which turns the glass green. To counter this for clear "flint" glass, we must add decolorizers (Selenium/Cobalt), which adds further cost.

| Trade-off Category | Impact of Adding Alumina | Consequence for Production |

|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature | Increases significantly. | Higher fuel cost; reduced furnace life. |

| Viscosity | Increases (Stiffer glass). | Slower bubble removal; harder to form complex shapes. |

| Clarity | Risk of cords/stones. | potential for visual defects; higher QC rejection rate. |

| Raw Material Cost | Higher. | Unit price increase of 5-15%. |

| Forming Speed | Slower (narrower working range). | Reduced output (Bottles Per Minute). |

How should the right Al₂O₃ level be specified for different uses like hot-fill, pasteurization, and steam sterilization?

Over-specifying glass composition wastes money, while under-specifying leads to catastrophic line failures. Matching the chemical durability to the thermal intensity of your process is the key to cost-effective procurement.

For standard hot-fill (up to 85°C), a standard soda-lime with 1.5-2.0% Al₂O₃ is sufficient if process controls are good. For rigorous pasteurization or retort sterilization (>121°C), specify "Modified Soda-Lime" or "Type II" glass with 2.5-3.5% Al₂O₃ to ensure survival through aggressive thermal cycling.

Defining the Thermal Load

When clients ask me, "How much alumina do I need?", I ask them to describe their "Thermal Profile."

-

Cold Chain / Ambient Fill: (Juice, Water, Spirits). No heat involved. Standard glass is perfect. Alumina level is irrelevant for thermal shock (only needed for chemical durability against water/alcohol).

-

Standard Hot Fill: (Teas, Isotonic drinks). Filled at 85°C, cooled to 35°C. The ΔT is ~50°C. Standard glass can work if pre-heated, but a slightly higher alumina content (2.0%+) provides a safety buffer.

-

Tunnel Pasteurization: (Beer, Sauces). The bottle goes up to 65°C and down to 25°C. The cycle is slow. Standard glass is usually fine.

-

Retort / Autoclave: (Milk, Protein drinks, Pharma). Sterilization at 121°C under pressure. This is the danger zone. Standard soda-lime will likely fail or suffer surface degradation (blooming). Here, you must specify high-alumina or treated glass.

Specification Guidelines for Buyers

When writing a Request for Quotation (RFQ), you don’t usually specify the exact percentage of Al₂O₃ because factories run continuous tanks—we can’t change the recipe for one order. However, you can specify the performance class or the glass type.

-

Ask for "Type II Glass": In the pharma world, Type II is soda-lime glass treated to be resistant. It naturally implies a robust composition.

-

Specify "Super Flint" vs. "High White": Sometimes "Super Flint" recipes (used for premium spirits) have higher viscosity and slightly different alumina ratios for clarity and brilliance, which can inadvertently affect thermal properties.

-

The "Safety Factor": If you cannot change the glass composition (because you are buying from a stock mold), you must change the process. No amount of alumina will save a cold bottle filled with boiling water.

| Application | Temperature Max | Thermal Risk | Recommended Al₂O₃ / Glass Spec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spirits / Wine | Ambient | None | Standard Flint (1.5% – 1.8%) |

| Hot Fill (High Acid) | 85°C – 90°C | Moderate (ΔT ~50°C) | Standard or Optimized (2.0% – 2.2%) |

| Pasteurization | 60°C – 70°C | Low (Slow Cycle) | Standard Flint (1.5% – 2.0%) |

| Retort / Sterilization | 121°C | High / Extreme | High Alumina (3.0%+) or Borosilicate |

| Pharma (Injectable) | Varies | Chemical Leaching | Type I Borosilicate or Type II Treated |

Which verification tests and supplier documents best confirm heat-resistance improvement after Al₂O₃ adjustment?

Trusting a supplier’s claim of "high thermal resistance" without data is a gamble. Validated lab reports are the only proof that the chemical adjustments have actually translated into physical resilience.

Request a Chemical Composition Analysis (XRF) to verify Al₂O₃ content, followed by a Dilatometer Test to confirm the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE). Finally, the ASTM C149 Thermal Shock Test provides the ultimate functional proof of the bottle’s performance limits.

1. Chemical Analysis (XRF)

The first step is to confirm the glass actually contains what was promised. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) is the standard method.

-

Document: Certificate of Analysis (COA) – Composition.

-

What to look for: Look at the Oxide % table.

-

SiO₂: ~70-74% -

Na₂O: ~12-15% -

Al₂O₃: Is it >2.0%? If it’s 1.5%, it’s standard glass. If it’s 3.0%, it’s high alumina.

-

2. Physical Property: CTE Measurement

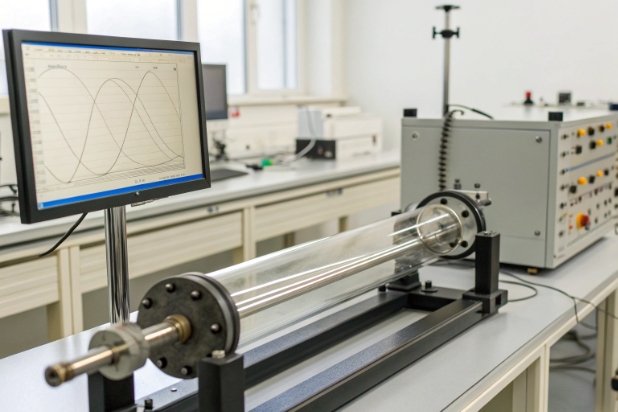

Knowing the composition is good, but knowing the expansion rate is better. A Dilatometer measures the expansion of a glass rod as it is heated.

-

Document: Physical Properties Data Sheet.

-

Metric: Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion (0-300°C).

-

Target: Standard soda-lime is ~90 x 10⁻⁷ K⁻¹. If your supplier claims high heat resistance, this number should be lower (e.g., 85 or 80). If the number is still 90, the extra alumina isn’t helping thermal shock.

3. Functional Testing: ASTM C149

This is the real-world test. As mentioned in previous discussions, we heat the bottles and plunge them into cold water.

-

The "Step Test": We don’t just pass/fail at 42°C. For high-alumina validation, we increase the ΔT by 2°C increments until breakage.

-

Analysis: We compare the "Mean Failure Temperature" of the standard batch vs. the high-alumina batch.

-

Standard Batch Mean Failure: ΔT 50°C.

-

High Alumina Batch Mean Failure: ΔT 60°C.

-

This statistically proves the improvement.

-

4. Hydrolytic Resistance (USP <660>)

Since alumina improves chemical durability, a "Water Resistance" or "Grain Test" is a proxy for high alumina content.

-

Test: USP Type Test (Surface Glass Test).

-

Result: If the glass passes as Type II (treated) or shows very low alkali release, it confirms the stabilizing effect of the alumina.

| Test Method | Purpose | Document/Standard | Success Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRF Analysis | Verify Al₂O₃ % | Composition COA | Al₂O₃ > 2.5% (for high resistance). |

| Dilatometer | Measure Expansion | Physical Data Sheet | CTE < 85 x 10⁻⁷/°C. |

| ASTM C149 | Thermal Shock | QC Report | 100% Pass at ΔT 50°C (vs standard 42°C). |

| USP <660> | Chemical Durability | Type Test Report | Low titration values (Acid resistance). |

| Density Check | Glass Density | QC Report | Slight density increase (Alumina is heavy). |

Conclusion

Alumina is a powerful tool in the glassmaker’s arsenal. By modifying the molecular network, it lowers thermal expansion and boosts chemical durability, offering a vital safety margin for hot-fill and sterilization processes. However, it comes with higher production costs and technical challenges. At FuSenglass, we help you balance these factors—specifying the right alumina level to ensure your bottles survive the line without breaking the budget.

Footnotes

-

A chemical compound of aluminum and oxygen with the chemical formula Al₂O₃. ↩

-

A hard, unreactive, colorless compound that occurs as the mineral quartz and as a principal constituent of sandstone and other rocks. ↩

-

The common name for sodium carbonate, a key ingredient in glass manufacturing. ↩

-

A machine that uses steam under pressure to kill harmful bacteria, viruses, fungi, and spores. ↩

-

Stress caused by rapid temperature changes, potentially causing glass fracture. ↩

-

Stress induced in a body when some or all of its parts are not free to expand or contract in response to temperature changes. ↩

-

A measure of the ability of a material to withstand changes in length when under lengthwise tension or compression. ↩

-

A measure of a fluid’s resistance to flow. ↩

-

An abundant rock-forming mineral typically occurring as colorless or pale-colored crystals. ↩

-

A measure of the bending of a ray of light when passing from one medium into another. ↩