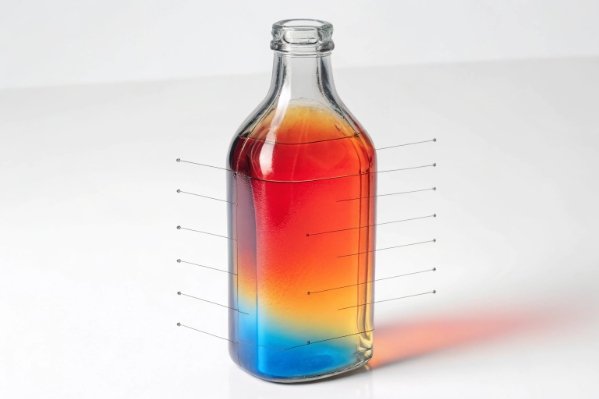

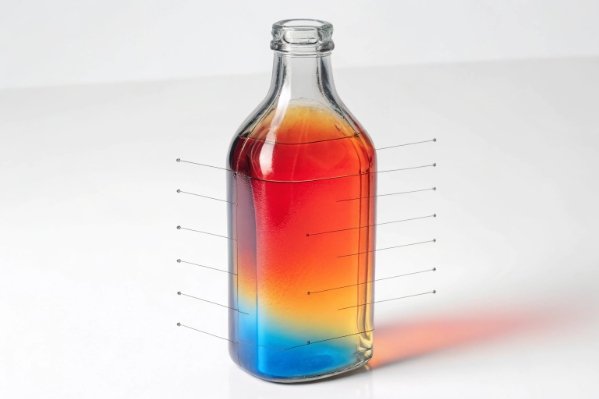

While the base often fails due to sheer mass (thermal lag), the shoulder is the "Achilles’ Heel" of the bottle for a different reason: it is the convergence point of structural geometry, glass distribution, and mechanical impact.

Yes, the bottle shoulder is frequently the least heat-resistant zone, primarily because it is the site of the most aggressive glass thinning (stretching) and mechanical contact. Thermal stress seeks out surface imperfections, and the shoulder is often where "settle waves" (thickness variations) and impact bruises accumulate, creating weak points that snap under temperature changes.

The "Stress Magnet" of the Bottle

At FuSenglass, when we analyze breakage from a pasteurization tunnel or a hot-fill line, 60% of the failures originate at the heel, but the remaining 40%—and often the most unpredictable ones—start at the shoulder.

The shoulder is the transition zone. It is where the bottle transforms from a wide cylinder (the body) into a narrow tube (the neck). In physics, any geometric transition acts as a "Stress Concentrator 1."

Unlike the base, which fails because it is too thick, the shoulder often fails because it is too thin. During the glass forming process, the shoulder is the part of the bubble that stretches the most. If the process isn’t perfectly controlled, you get a "Thin Shoulder." When hot liquid hits this thin glass, it expands instantly. If the thicker neck above it or the body below it doesn’t expand as fast, the shoulder tears apart.

Vulnerability Factor Comparison

| Zone | Primary Thermal Risk | Cause | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base/Heel | Thermal Lag | Glass is too thick/insulating. | Circumferential Separation (Bottom drops out). |

| Shoulder | Thermal Shock + Impact | Glass is thin; Surface is bruised. | Vertical Check or Butterfly Crack. |

| Sidewall | Vacuum Collapse | Large surface area. | Panelling (Sucking in). |

| Neck/Finish | Crazing | Complex thread geometry. | Fine surface cracks (Crazing). |

What makes the bottle shoulder more prone to thermal stress than the base and sidewalls?

The shoulder faces a "double whammy": it is structurally complex and mechanically abused.

The shoulder is uniquely vulnerable because it combines "Geometric Stress" (bending forces from the shape change) with "Mechanical Damage" (abrasion). On filling lines, bottles bump shoulder-to-shoulder. These microscopic bruises act as initiation sites for cracks when thermal stress is applied.

The Bruised Apple Effect

Glass is strong in compression but weak in tension. Thermal shock creates tension. However, for tension to break the glass, it usually needs a "starting point"—a flaw.

1. The "Bumper" Problem:

Look at a filling line. Where do the bottles touch? The shoulder (and sometimes the heel). This "shoulder-to-shoulder" contact creates tiny micro-cracks or "checks." A pristine bottle might withstand a $\Delta T$ of 60°C. A bottle with a scratched shoulder might fail at a $\Delta T$ of only 30°C. The thermal stress 2 rips open the impact flaw.

2. The Stretching Zone:

In the mold, the parison 3 (the blob of hot glass) hangs by the neck. Gravity pulls it down. The shoulder area stretches the most before the blow air expands it. This often leads to the shoulder being the thinnest part of the entire bottle. Thin glass heats up fast, but if it’s surrounded by thicker glass (the neck insert), the differential expansion shears the thin glass.

How do shoulder shape, glass thickness, and embossing influence thermal shock resistance?

Design choices can turn a robust bottle into a fragile one; sharp angles and decoration are enemies of thermal endurance.

Square shoulders and embossed logos drastically reduce thermal resistance. Sharp radii concentrate stress at the corners, while embossing creates "notch effects" (variation in wall thickness) that disrupt heat transfer, creating localized hot spots where cracks can originate.

Designing for Disaster (and how to avoid it)

We often see marketing teams demand sharp, angular designs that give production engineers nightmares.

1. The Square Shoulder:

A 90-degree shoulder (like a gin bottle) is a stress trap. When the bottle expands from heat, the forces converge at the corner.

- The Fix: Use a large radius. A "sloping" shoulder (like a Bordeaux wine bottle) is vastly superior for heat resistance because it distributes the expansion force along a curve.

2. Embossing (Logos/Text):

Putting a logo on the shoulder is popular. But embossing changes the glass thickness locally (thick-thin-thick).

-

The Risk: This creates uneven heating. The thick logo stays cold; the thin background gets hot. The border of the letter becomes a stress riser.

-

Rule: If you hot-fill, avoid heavy embossing on the shoulder contact points.

3. Settle Wave (The Thickness Ripple):

This is a defect where the glass wall thickness fluctuates rapidly near the neck. It acts like a perforation line. Under thermal shock 4, the bottle will zip open along this wave.

Design Impact Matrix

| Feature | Thermal Resistance Impact | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Sloped Shoulder | Positive (+) | Distributes stress; uniform expansion. |

| Square Shoulder | Negative (-) | Concentrates stress at the corner. |

| Embossing | Negative (-) | Creates variable thickness/stress risers. |

| Wide Diameter | Neutral | Depends on wall uniformity. |

Which forming and annealing factors most often create weak points around the shoulder area?

The shoulder is where the "parison" (pre-form) meets the final mold, making it a hotspot for forming defects.

The "Settle Blow" process in manufacturing is the critical moment. If the glass isn’t perfectly distributed, it creates a "Settle Wave" (a ring of thin glass) at the shoulder. Furthermore, inside the annealing lehr, shoulders often cool unevenly due to airflow blockage from adjacent bottles, leaving residual tension.

The Birth of a Weak Shoulder

1. The Settle Wave (Forming Defect):

In the "Blow-Blow" process, we drop a gob 5 of glass into a blank mold and blow air down to form the neck ("Settle Blow"). If the glass is too cold or the timing is off, a ripple forms where the gob folds over. This ripple ends up in the shoulder.

- Result: A localized thin spot that breaks easily under thermal load.

2. Uneven Cooling (Annealing Defect):

In the lehr 6 tunnel, bottles travel in a pack. The shoulders are often touching or shielding each other from the cooling air.

- Result: The necks (exposed) cool fast. The bodies (exposed) cool fast. The shoulders (shielded by neighbors) stay hot. This differential cooling locks stress into the shoulder curve. We have to adjust the lehr airflow to ensure "down-draft" cooling reaches the gaps between shoulders.

What tests and handling practices reduce shoulder cracking during hot-fill, pasteurization, or sterilization?

You cannot fix a weak shoulder on the filling line, but you can stop breaking it.

To reduce shoulder failure, lines must minimize "Metal-to-Glass" and "Glass-to-Glass" impact using soft guide rails. Quality control should implement "Pendulum Impact Testing" on the shoulder specifically, followed by Thermal Shock testing, to verify that minor bumps aren’t turning into thermal failure points.

The Prevention Protocol

1. Impact + Thermal Correlation:

Standard QC does a thermal shock test on new bottles. This is insufficient.

- Best Practice: Impact the bottle shoulder lightly (simulating line contact), then run the thermal shock test. If the bottle fails, your glass is too fragile (impact sensitivity).

2. Line Management:

-

Soft Handling: Replace metal guide rails with Polymer (HDPE) or brush guides. Metal scratches glass; plastic does not.

-

Back-Pressure: Reduce the line pressure (accumulation). If bottles are grinding against each other at the shoulder, they are creating flaws that will pop in the pasteurizer 7.

3. The "Settle Wave" Check:

-

Visual: Hold the bottle up to a light board. Look for a horizontal wavy line in the shoulder glass.

-

Thickness: Use a Hall Effect gauge 8 to measure the thickness above and below the wave. If the variance is > 0.5mm, reject the batch for hot-fill.

Testing Strategy

| Test | Target | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Shock | General Resistance | $\Delta T \ge 42^\circ C$. |

| Pendulum Impact | Shoulder Strength | Withstand > 0.6 Joules impact. |

| Scratch Test | Surface Durability | Coating check (Polyethylene 9 presence). |

| Thickness Gauge | Settle Wave | Min thickness > 1.2mm at shoulder. |

Conclusion

The shoulder is the "front line" of the bottle. It takes the hits and bridges the structural transition. By smoothing out the curves, eliminating settle waves, and cushioning your filling line, you can protect this critical zone from thermal failure.

Footnotes

-

A location in an object where the stress is significantly greater than the surrounding area. ↩

-

Stress induced in a body when some or all of its parts are not free to expand or contract in response to temperature changes. ↩

-

A semi-molten glass tube which is blown into the final shape of the bottle. ↩

-

Mechanical stress caused by a rapid change in temperature, often leading to fracture. ↩

-

A precise lump of molten glass cut from the feeder and delivered to the forming machine. ↩

-

A specialized oven used in glass manufacturing to anneal and cool bottles under controlled conditions. ↩

-

Equipment used to heat-treat products to kill pathogens, often involving thermal stress on containers. ↩

-

A precision instrument used to measure the wall thickness of non-magnetic materials like glass. ↩

-

A common polymer applied as a cold-end coating to reduce friction and prevent surface damage. ↩