While the annealing point is a fixed chemical property, the success of the process that happens at this temperature is the single biggest factor in determining if a bottle survives thermal stress.

Yes, the annealing point dictates the critical temperature zone where internal stresses are relieved. Proper heat treatment at this specific point ensures the removal of tension "memory" from the forming process, which is essential for maximizing the bottle’s thermal shock resistance and preventing spontaneous breakage.

The "Reset Button" for Glass Strength

At FuSenglass, we consider the annealing lehr 1 (oven) the most critical quality control machine in the entire factory. When a glass bottle is blown into a mold, it cools unevenly—the outside hardens while the inside is still soft. This creates massive "residual stress 2." If left unchecked, this stress acts like a pre-loaded spring, waiting for the slightest bump or temperature change to shatter the bottle.

The Annealing Point is the specific temperature where the glass viscosity allows these internal stresses to relax in a matter of minutes. It is the "reset button" for the glass structure.

If we miss this target—either by running the belt too fast or the temperature too low—the bottle retains that stress. A bottle with poor annealing might look perfect, but its "thermal budget" is already spent. When you fill it with hot jam or wash it with hot water, it explodes because it cannot handle the additional stress of the temperature change.

Viscosity Point Definitions

| Term | Viscosity (Poise) | Approx Temp (Soda-Lime) | Practical Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Softening Point | $10^{7.6}$ | ~ 725°C | Glass deforms 3 under its own weight. |

| Annealing Point | $10^{13}$ | ~ 550°C | Stress is relieved in ~15 minutes. |

| Strain Point | $10^{14.5}$ | ~ 510°C | Glass becomes rigid; stress is "locked in". |

| Working Point | $10^4$ | ~ 1050°C | Glass is fluid enough to shape. |

What is the annealing point of bottle glass, and how is it different from the softening point and strain point?

Understanding these three temperature benchmarks is crucial for controlling the transition from liquid to solid without locking in destructive tension.

The annealing point of standard soda-lime bottle glass is approximately 550°C. This is significantly lower than the softening point (725°C), where glass loses shape, but higher than the strain point (510°C), below which the glass is effectively a solid and no further stress relief is possible.

The Critical Temperature Windows

In glass physics, we don’t have a distinct "freezing point" like water. We have a gradual thickening.

1. Softening Point (~725°C):

This is the danger zone for shape. If we heat the bottle here, the neck will droop, and the bottle will warp. We must stay well below this during annealing to maintain the bottle’s dimensions.

2. The Annealing Range (The "Soak" Zone: 520°C – 560°C):

This is the magic window. At the Annealing Point (550°C), the molecules are still mobile enough to rearrange themselves and relieve tension, but the glass is stiff enough to hold its shape. We must hold the bottles here long enough for the temperature to equalize completely throughout the wall thickness.

3. Strain Point (~510°C):

This is the "point of no return." Once the glass cools below the strain point 4, the structure is set in stone. Any stress remaining in the glass at this point becomes permanent. Ideally, we want the stress to be near zero before we cross this line.

Comparison of Thermal Points

| Point | Physical State | Manufacturing Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Softening Point | Viscous Plastic | Limit for Secondary Firing (Decals). |

| Annealing Point | Viscoelastic Solid | Target Temp for Stress Relief (Lehr). |

| Strain Point | Rigid Solid | Cooling rate must be slow until passing this. |

How does annealing quality (residual stress control) impact thermal shock resistance and cracking risk in glass bottles?

Think of a glass bottle as having a "strength bank account." Residual stress makes a withdrawal before the bottle even leaves the factory.

Annealing quality directly determines the "Thermal Shock Budget" of the bottle. A poorly annealed bottle has high residual tension, meaning it might shatter with a $\Delta T$ of only 30°C. A perfectly annealed bottle (Grade 1) has zero internal load, allowing it to withstand the maximum theoretical $\Delta T$ of 42°C+ without cracking.

The Stress Superposition Principle

Why does a bottle break?

$$Total Stress = Residual Stress (Manufacturing) + Applied Stress (Thermal Shock)$$

Glass has a fixed tensile strength 5. If that limit is 50 MPa:

-

Scenario A (Poor Annealing): The bottle has 20 MPa of "locked-in" residual tension from fast cooling. You pour hot coffee in it, adding 35 MPa of thermal stress. Total = 55 MPa. CRACK.

-

Scenario B (Good Annealing): The bottle has 0 MPa of residual tension. You pour the same hot coffee (35 MPa). Total = 35 MPa. SAFE.

At FuSenglass, we use this principle to improve heat resistance without changing the glass formula. By simply slowing down the cooling process, we remove the "pre-load" on the glass, making it robust enough for hot-filling or pasteurization lines.

Impact on Failure Modes

| Annealing Quality | Residual Stress Level | Thermal Shock Limit ($\Delta T$) | Risk Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (Excellent) | Near Zero | High (> 45°C) | Ideal for Candles, Jams, Hot-Fill. |

| Grade 2 (Standard) | Low | Standard (~ 42°C) | Safe for Beverages, Ambient Fill. |

| Grade 3 (Fair) | Moderate | Low (~ 35°C) | Risk of breakage in winter/transit. |

| Grade 4/5 (Poor) | High | Very Low (< 25°C) | Spontaneous Explosion Risk. |

What annealing lehr temperature profile and cooling rate controls help improve heat durability without changing the glass formula?

You don’t need expensive borosilicate ingredients to fix breakage; you need precise time-temperature management in the lehr tunnel.

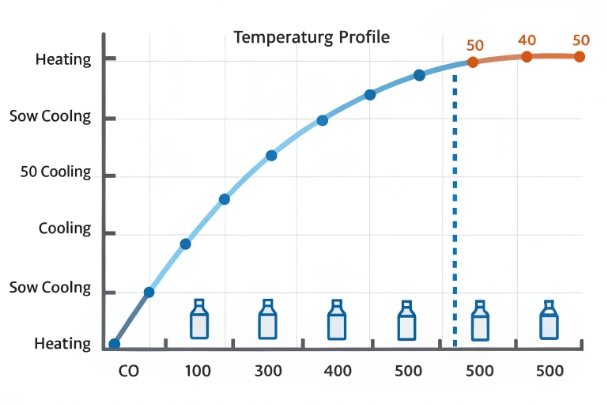

To improve heat durability, the lehr profile must maintain a "Soak Time" at 550°C to equalize temperature, followed by a "Slow Cool" rate of < 5°C/min through the annealing-to-strain range. This controlled descent prevents the re-introduction of temporary stress before the glass solidifies.

Tuning the Lehr for Performance

The Lehr is a long tunnel oven (often 30+ meters). Optimizing the curve is an art.

Step 1: Re-Heating (The Equalizer)

Bottles enter the lehr at varying temps (some edges cool fast). We heat them up slightly to just above the Annealing Point (555°C). This ensures every millimeter of glass is at the same starting viscosity 6.

Step 2: The Critical Soak

We hold the temp steady for 10-20 minutes. This allows stress relaxation. For heavy bottles (spirits/candles), we must extend this time because thick glass takes longer to relax.

Step 3: The Slow Cool (The Critical Zone)

This is where mistakes happen. We must cool from 550°C down to 500°C (past the Strain Point) very slowly. If we cool too fast here, the outside hardens while the inside is still relaxing, locking in new tension. We aim for a drop of only 3-5 degrees per minute.

Step 4: Fast Cool

Once we are below 450°C (well below Strain Point), the glass is solid. We can blast it with cold air to bring it to room temp quickly without hurting the structure.

Process Control Strategy

| Zone | Temp Range | Action | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry/Heating | 450°C $\to$ 560°C | Rapid Heat | Bring all ware to uniform temp. |

| Annealing Zone | 560°C $\to$ 540°C | Hold / Soak | Relieve internal molecular stress. |

| Retarding Zone | 540°C $\to$ 500°C | Slow Cool | Prevent new stress formation. |

| Cooling Zone | 500°C $\to$ 30°C | Fast Cool | Cool for handling/packing. |

What tests (polariscopic stress check, thermal shock ΔT test) should buyers require to verify annealing performance batch to batch?

You cannot see stress with the naked eye; you need polarized light to reveal the hidden tension maps that predict failure.

Buyers must require "ASTM C148 Polariscopic Examination" for every batch, rejecting any ware > Grade 2. Additionally, periodic "ASTM C149 Thermal Shock" destructive testing confirms that the annealing process effectively translated into real-world temperature resistance.

The QC Toolkit

1. The Polariscope (ASTM C148):

This is a non-destructive test. We place the bottle between two polarized filters 7.

-

What we see: Stress bends light, creating a "Maltese Cross" pattern or colored rings on the bottom of the bottle (birefringence 8).

-

The Rating: We compare the color intensity to standard calibrated discs.

-

Grade 1-2: Real Commercial Annealing (Pass).

-

Grade 3: Warning Limit.

-

Grade 4-5: Reject. These bottles are "tempered" and unstable.

-

2. Thermal Shock Test (ASTM C149):

This validates the result. We take 20 bottles, heat them in water to 65°C, and plunge them into 23°C water ($\Delta T = 42^\circ C$).

- Pass Criteria: 100% survival. If even one breaks, we know the lehr profile drifted, or the annealing was insufficient for the glass thickness.

3. Fragmentation Test:

If a bottle breaks, look at the pieces.

-

Annealed Break: Large, lazy cracks. 3-4 pieces.

-

Stressed Break: Shatters into many small, sharp slivers (like safety glass 9, but uncontrolled). This indicates high residual energy.

Quality Specification Summary

| Test Method | Frequency | Acceptance Limit | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polariscope | Every 2 Hours | Max Grade 2 | Monitor Lehr performance. |

| Thermal Shock | Once per Shift | $\Delta T \ge 42^\circ C$ | Confirm functional safety. |

| Scratch Test | Daily | No excessive marking | Check surface lubricity (coating). |

Conclusion

The annealing point is the anchor of glass stability. By strictly controlling the cooling rate through this 550°C window, we ensure that every FuSenglass bottle is stress-free 10 and ready for the thermal challenges of your filling line.

Footnotes

-

An industrial oven designed to slowly cool glass to relieve internal stresses. ↩

-

Tension that remains in a solid material after manufacturing or processing. ↩

-

The tendency of a material to change shape under applied load or its own weight. ↩

-

The temperature below which glass behaves as a rigid solid and stress cannot be relieved. ↩

-

The maximum stress a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before failing. ↩

-

A measure of a fluid’s resistance to flow; critical for determining glass working points. ↩

-

Optical filters that block light waves oscillating in specific directions, used to see stress. ↩

-

The optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. ↩

-

Glass that has been processed to increase its strength compared to normal glass. ↩

-

Reference to ASTM C148, the standard test method for polariscopic examination of glass containers. ↩