A cloudy bottle suggests a spoiled product to the consumer, destroying brand value instantly. Chemical corrosion is often the invisible culprit turning premium clear glass into dull, milky rejects.

Yes, acid and alkali corrosion significantly reduce light transmittance and increase haze. Chemical attack roughens the glass surface on a microscopic level, creating pits and porous layers that scatter light rather than allowing it to pass through, resulting in a permanent "frosted" or foggy appearance.

The Physics of Clarity vs. Corrosion

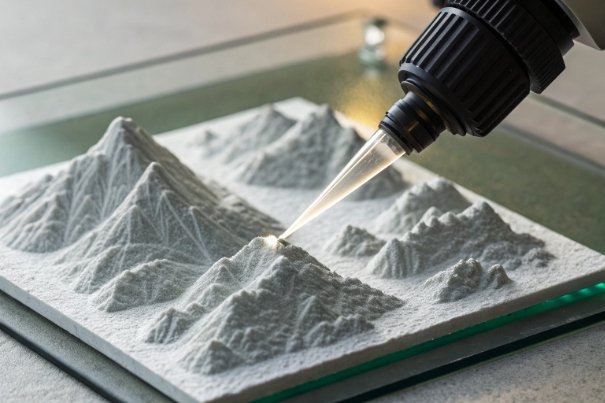

As the face of FuSenglass, I often explain to clients that "transparency" is simply the absence of obstacles. A perfect glass surface allows light to pass through with minimal deviation. However, industrial washing, acidic juices, or alkaline storage conditions can turn the glass surface into a chaotic landscape of peaks and valleys.

This phenomenon is optical physics in action. When corrosion occurs, it doesn’t just "dirty" the glass; it physically alters the topography.

- Direct Transmission Loss: The roughened surface reflects more light at the interface rather than letting it enter the bottle.

- Haze (Scattering): This is the more damaging effect. Instead of light rays traveling straight through to illuminate the beverage, they hit microscopic pits and scatter in all directions.

For a premium spirit or perfume, this is catastrophic. The liquid inside loses its sparkle. The bottle looks "tired" or "sick." Understanding the mechanism is the first step to saving your shelf appeal.

Mechanisms of Attack

- Alkali Attack (Dissolution): Strong bases (NaOH, KOH) dissolve the silica network. This removal is rarely uniform. It digs out softer areas of the glass first, creating deep, broad pits. This typically results in a white, opaque "fog."

- Acid Attack (Leaching): Acids (except HF) leach out sodium, leaving a silica-rich "gel" layer. As this layer thickens and hydrates, it changes the refractive index 1 of the surface. Initially, this causes iridescence (rainbows), but as the layer cracks or roughens, it turns into a diffuse haze.

| Property | Pristine Glass | Corroded Glass | Visual Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Topography | Smooth (< 10nm roughness) | Rough (> 500nm roughness) | Loss of gloss. |

| Light Path | Direct / Specular | Scattered / Diffuse | Milky / Foggy appearance. |

| Transmittance (%) | > 90% (Clear Flint) | < 80% (Severe Etch) | Product looks dark. |

| Haze (%) | < 1% | > 5% | Product looks blurry. |

To control this, we must identify the specific variables in your production line that are eating your glass.

How does chemical etching increase haze and reduce light transmittance?

Etching turns the glass surface into a microscopic mountain range. This physical restructuring disrupts light passage, converting a transparent vessel into a translucent one.

Chemical etching increases haze by increasing the Root Mean Square (RMS) roughness of the glass surface. As the roughness amplitude approaches the wavelength of visible light (400-700nm), scattering dominates over transmission, causing the glass to appear white or frosted.

The Scattering Effect

Imagine shining a flashlight through a clear window versus a frosted shower door. That is the difference between a new bottle and a corroded one.

- Specular Transmission: In a new bottle, light enters at one angle and exits at the same angle. You can clearly see the product color and clarity.

- Diffuse Transmission: In an etched bottle, the light hits a pit and bounces off at a random angle.

This "noise" in the light signal makes the contents look murky. For high-end brands, this implies the product itself has degraded or precipitated, even if the liquid is fine.

The "Frosting" Process

Interestingly, we use this exact principle intentionally to create frosted bottles using Hydrofluoric Acid 2 (HF). We purposely corrode the glass to create a premium matte look. The problem arises when this happens unintentionally and unevenly due to improper cleaning with caustics or exposure to harsh environmental conditions. The result is not a beautiful matte finish, but a patchy, sickly haze that looks like dirt residue but cannot be wiped off.

Iridescence vs. Haze

Before the glass turns fully white, it often goes through an "Iridescent" phase. This is common in dishwasher damage. The leached silica layer acts like a thin film of oil on water. It splits the light spectrum, causing purple and green reflections. This is the first warning sign that transmittance is being compromised.

| Defect Stage | Surface Condition | Optical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Leaching | Silica gel layer forms. | Iridescence: Rainbow interference patterns. |

| Stage 2: Light Etch | Micro-pitting (nanometers). | Loss of Gloss: Surface looks dull, not shiny. |

| Stage 3: Haze | Pitting > wavelength of light. | Cloudiness: Objects behind glass look blurry. |

| Stage 4: Frost | Deep structural erosion. | Opacity: Cannot see through clearly; white appearance. |

So, which chemicals are the most effective at destroying your clarity?

Which process variables most strongly impact transparency loss?

Not all chemicals are equally destructive. Specific combinations of pH and temperature can ruin a batch of glass in minutes, while others take years.

Hydrofluoric acid causes immediate opacity. Strong alkalis (pH > 13) at high temperatures (>70°C) cause rapid hazing. The degradation rate follows an Arrhenius relationship with temperature, doubling for every 10°C rise, while concentration thresholds dictate the onset of permanent pitting.

Chemical Hierarchy of Destruction

- The Nuclear Option: Hydrofluoric Acid (HF). As discussed in previous posts, any fluoride-containing cleaner will instantly react with silica. Even at 1% concentration, it creates a fluoride sludge that blocks light.

- The Heavyweights: Strong Alkalis (NaOH, KOH). Used in bottle washing. If the concentration exceeds 3-5% and the temperature is high, they dissolve the network.

- The Slow Burn: Chelating Acids. Acids like Citric or EDTA 3-based cleaners can be deceptive. They strip metals (calcium/stabilizers) from the glass surface, making it more porous over time, eventually leading to haze.

The Critical Role of Temperature

I tell my clients: "Heat is the accelerator."

You can store a bottle in 5% Caustic Soda at room temperature (20°C) for days with minimal haze. But heat that same solution to 85°C, and you will see visible etching in under an hour.

- Rule of Thumb: Keep washing temperatures as low as hygiene permits. If you must use high heat, reduce the chemical concentration.

Contact Time and Agitation

Corrosion is a surface reaction.

- Stagnant Soak: The dissolved glass stays near the surface, actually slowing down further attack (saturation).

- High Agitation/Spray: Fresh chemical is constantly hitting the glass, and the dissolved silica is washed away. This speeds up the etching process. Spray washers are more aggressive than soak tanks.

| Variable | High Transparency Risk | Low Transparency Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | HF, Ammonium Bifluoride, Hot NaOH | Nitric Acid, Neutral Detergents |

| Temperature | > 70°C (160°F) | < 40°C (100°F) |

| Concentration | > 5% Caustic | < 1% Caustic |

| State | Agitated / Sprayed | Stagnant Soak |

If you suspect damage, how do you prove it isn’t just dirty glass?

How can you measure transmittance and haze changes after chemical exposure?

Subjective visual checks are unreliable. Quantifying optical performance requires precision instruments that distinguish between light that passes through and light that is scattered.

Use a Spectrophotometer to measure Total Transmittance (%T) at 550nm for overall clarity. Use a Haze Meter (ASTM D1003) to quantify the percentage of scattered light. Visual comparison against "Limit Samples" provides a practical pass/fail check on the production floor.

Spectrophotometry: The Clarity Check

This instrument shines a beam of light through the bottle wall and measures how much exits the other side.

- The Metric: We typically look at % Transmittance at 550 nanometers (the middle of the visible spectrum, green-yellow).

- The Benchmark:

- Super Flint (New): ~91-92% Transmission.

- Standard Flint (New): ~89-90% Transmission.

- Corroded/Hazy: Drops to < 85%. A drop of just 2-3% is visible to the naked eye as "dullness."

Haze Meter (ASTM D1003): The Scattering Check

This is arguably more important for corrosion. A bottle can still let a lot of light through (high transmittance) but look milky (high haze).

- The Measurement: It measures the light that deviates more than 2.5 degrees from the incident beam.

- The Metric: Haze % 4.

- Pristine Glass: < 0.5% Haze.

- Visible Weathering: > 2.0% Haze.

- Frosted Look: > 10% Haze.

If your QC report shows Haze climbing from 0.5% to 1.5% after washing, you are actively destroying your inventory.

Visual Limit Samples

On the factory floor, operators don’t have spectrophotometers. We create "Limit Boards."

- Sample A: Perfect Bottle.

- Sample B: Borderline Acceptable (Slight dullness).

- Sample C: Reject (Visible Haze/Rainbows).

Operators hold bottles against a black background with side lighting to catch the scattering.

| Method | Measures | Best For | Typical Spec (New Glass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Total light passing through (%T). | Color purity, overall brightness. | > 90% (Clear) |

| Haze Meter | Scattered light (%). | Detecting etching/frosting. | < 1.0% |

| Visual (Black Background) | Glare / Reflection. | Rapid line inspection. | No visible clouding. |

| Gloss Meter | Surface reflection. | External coating dulling. | > 100 GU 5 |

You can measure the damage, but can you prevent it?

What glass composition and surface-protection options help maintain transparency?

Prevention is better than cure, especially since you cannot "polish" an etched bottle back to clarity. Choosing the right glass matrix or applying protective treatments is the only defense.

Borosilicate glass (Type I) offers superior resistance but is costly. For standard packaging, sulfur treatment (Type II) significantly improves hydrolytic resistance. External "Cold End Coatings" provide a sacrificial layer against abrasion and mild chemical attack, preserving the pristine glass surface.

The Glass Matrix: Type I vs. Type III

- Type III (Soda-Lime): The standard. It contains high alkali ($Na_2O$). It is vulnerable to haze if exposed to moisture or acids for long periods.

- Type I (Borosilicate): Contains Boron. It has a much tighter silica network. It is almost immune to acid attack and very resistant to alkali. If your product is highly aggressive (pH < 2 or > 11), you might need to upgrade to Type I, despite the cost.

Internal Treatment: The Sulfur Solution

For Type III glass, we can perform ammonium sulfate treatment inside the bottle during manufacturing.

- How it helps: It sucks the sodium out of the surface layer before the bottle ever leaves the factory.

- The Benefit: When you fill it with an acidic liquid, there is no sodium left to leach out. The surface remains smooth and clear. This effectively stops the "iridescence" and early-stage haze.

External Protection: Hot and Cold End Coatings

Glass bottles have coatings applied during manufacturing (Tin Oxide 6 + Polyethylene 7).

- Primary Function: Scratch resistance.

- Secondary Function: Transparency protection. A scratched bottle hazes much faster than a smooth one because the chemicals attack the cracks. These coatings keep the surface pristine.

- Caution: These coatings are organic. Strong caustic washes will strip them off. Once the coating is gone, the glass hazes rapidly due to physical scuffing and chemical attack.

| Option | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Type III | Low Cost, High Availability. | Prone to weathering/haze. | Fast-turnover beverages. |

| Type II (Treated) | High Chemical Resistance. | Slightly higher cost. | High-acid spirits, Pharma. |

| Type I (Borosilicate) | Extreme Clarity & Durability. | Very Expensive. | Lab chemicals, Ampoules. |

| Cold End Coating | Protects against scuffs. | Stripped by caustic wash. | Single-use bottles. |

Conclusion

Acid and alkali corrosion are the enemies of clarity. They rob your glass of its ability to transmit light by chemically roughening the surface. By monitoring Haze % and Total Transmittance, controlling your washing parameters, and selecting treated glass (Type II) where necessary, FuSenglass ensures your product is always seen in the best possible light.

Footnotes

-

A measure of how much the speed of light is reduced inside a medium compared to a vacuum. ↩

-

A highly corrosive acid capable of dissolving glass, used for etching and cleaning metals. ↩

-

A chemical used to bind metal ions, often found in detergents and food preservatives. ↩

-

Standard test method for haze and luminous transmittance of transparent plastics. ↩

-

Gloss Units, a scaling system used to measure the reflective quality of a surface. ↩

-

An inorganic compound used as a precursor in the production of glass coatings. ↩

-

A common plastic polymer used in packaging, films, and coatings. ↩