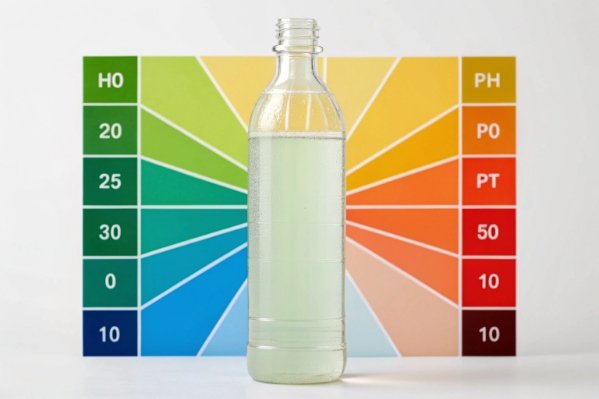

Glass seems invincible, but the wrong chemical concentration can silently destroy your packaging integrity. We must understand how pH intensity acts as the fuel for corrosion, turning a stable container into a source of contamination.

Concentration is the primary driver of chemical attack speed. While glass exhibits robust resistance to most acidic concentrations (pH < 7) due to the formation of a protective silica layer, it is highly vulnerable to increasing alkaline concentrations (pH > 9). As the concentration of hydroxide ions rises, the silicate network dissolves exponentially faster, leading to irreversible surface etching.

The Dose Makes the Poison: Understanding Concentration

At FuSenglass, we often remind our clients that "glass is chemically inert" is a relative truth, not an absolute one. The reality is that the chemical stability of a soda-lime bottle 1 is entirely dependent on the chemical environment it holds. The concentration of the attacking species—specifically the Hydrogen ions 2 ($H^+$) in acids and the Hydroxide ions 3 ($OH^-$) in alkalis—dictates the survival of the glass.

In my experience troubleshooting packaging failures, I see a clear divide. Acidic products (juices, wines, vinegars) generally interact with the glass in a slow, predictable manner called "leaching." You can double the concentration of citric acid, and the glass performance changes very little.

However, on the alkaline side (cleaning products, alkaline waters, industrial washes), the relationship is volatile. A small increase in concentration—shifting from pH 10 to pH 12—can change a stable bottle into one that clouds and fails within days. This is because concentration in the alkaline range triggers a fundamental breakdown of the glass skeleton itself.

For a brand owner, understanding this "Concentration-Corrosion Curve" is vital. It allows you to predict whether your new "Extra Strength" cleaner will survive in a standard bottle, or if your new "High pH" water requires a specialized borosilicate container.

Concentration Impact Overview

| Chemical Environment | Active Species | Effect of Increasing Concentration | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral (pH 7) | Water ($H_2O$) | Slow hydration of surface. | Very Low. |

| Weak Acid (pH 4-6) | $H^+$ (Low Conc) | Minimal ion exchange. | Low. (Standard Food Safe). |

| Strong Acid (pH < 2) | $H^+$ (High Conc) | Protective silica layer forms faster. | Low to Moderate. (Self-limiting). |

| Weak Alkali (pH 8-9) | $OH^-$ (Low Conc) | Slow surface modification. | Moderate. (Long-term haze risk). |

| Strong Alkali (pH > 12) | $OH^-$ (High Conc) | Rapid Dissolution. Network destroyed. | Critical. (Etching, weight loss). |

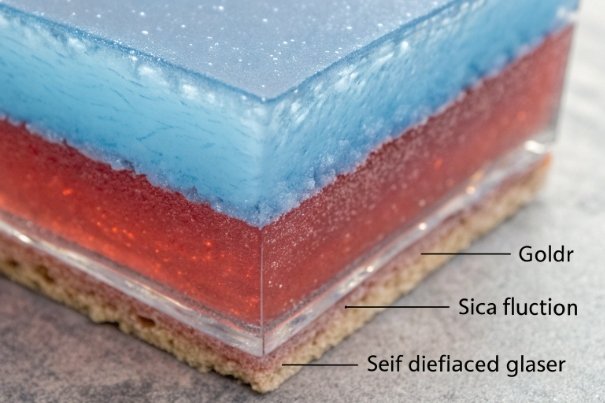

To explain why alkalis are the true enemy of glass, we must look at the atomic battlefield.

Why does higher pH (stronger alkali) often attack soda-lime glass faster than most food-grade acids?

It is a battle between "defense" and "destruction." Acids trigger a reaction that builds a shield, while strong alkalis trigger a reaction that tears down the wall.

Higher pH means a higher concentration of Hydroxide ions (OH-), which attack the silicon-oxygen bonds directly, dissolving the glass network layer by layer. In contrast, acids only cause an ion exchange (swapping protons for sodium) that leaves the silica skeleton intact. This silica skeleton forms a "gel layer" that acts as a diffusion barrier, slowing down further acid attack, whereas alkali attack has no such braking mechanism.

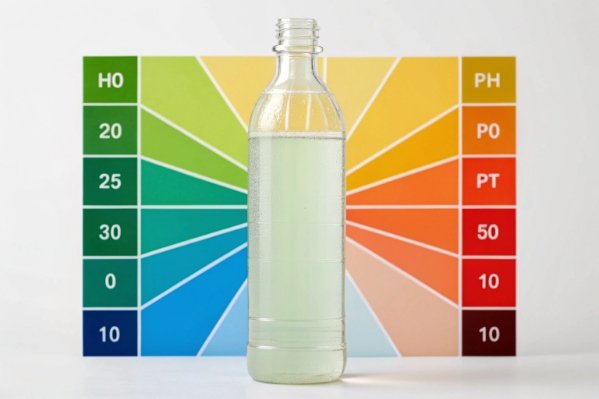

The Protective Barrier vs. Total Destruction

When I explain this to non-chemists, I use the analogy of a brick wall. The bricks are Silica, and the mortar is Sodium/Calcium.

1. The Acid Attack (Self-Limiting):

When strong acid (high concentration) hits the glass, it attacks the mortar (Sodium). The acid eats away the mortar near the surface.

- The Result: The bricks (Silica) are left behind. They form a porous, silica-rich layer on the surface.

- The Defense: This layer of "bricks" blocks the acid from reaching deeper into the wall. As the layer gets thicker, the corrosion slows down. This is why you can store 30% Hydrochloric Acid in a glass bottle for years. The glass builds its own shield.

2. The Alkali Attack (Linear/Exponential):

When strong alkali (high pH) hits the glass, the Hydroxide ions ($OH^-$) don’t care about the mortar. They attack the bricks themselves.

- The Mechanism: The $OH^-$ severs the siloxane bonds 4 ($Si-O-Si$) to form soluble silicates ($Si-O^- Na^+$).

- The Result: The wall is dismantled brick by brick. The surface recedes.

- No Defense: Because the surface is constantly being removed, fresh glass is always exposed to the attack. There is no protective gel layer 5 formed. The higher the concentration of alkali, the faster the bricks are removed.

Paradox of Acid Concentration:

Interestingly, extremely high acid concentrations can sometimes be less corrosive than moderate ones. Glass corrosion requires water. If you have 98% Sulfuric Acid, there is very little water to hydrate the ions, and the attack is incredibly slow. Diluting it to 10% can actually make it more aggressive initially, but the silica shield eventually stops it.

Mechanism Comparison Table

| Feature | Acid Attack (Low pH) | Alkali Attack (High pH) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Action | Leaching (Ion Exchange). | Etching (Dissolution). |

| Target | Network Modifiers (Na, Ca). | Network Formers (Si, Al, B). |

| Protective Layer? | Yes. Silica-rich gel layer forms. | No. Surface is stripped away continuously. |

| Time Profile | Square root of time ($t^{1/2}$). Slows down. | Linear with time ($t$). Constant rate. |

| Visual Effect | Usually none (glass stays clear). | Frosted, rough, pitted surface. |

So, where is the tipping point? When does the glass go from "safe" to "ruined"?

At what acid/alkali concentration ranges do glass bottles typically shift from “stable” to visible etching or haze?

There is a safety zone and a danger zone. Knowing these thresholds helps you decide if you need standard soda-lime glass or if you need to upgrade to a more resistant material.

Glass bottles remain visually stable in acidic solutions virtually regardless of concentration (down to pH 0), with defects only appearing as invisible chemical leaching. However, in alkaline solutions, the "Danger Zone" begins at pH 9. Visible etching and haze typically manifest rapidly once the pH exceeds 11, where the concentration of hydroxide ions becomes sufficient to break the silica network at a macroscopic rate.

The Visibility Threshold

At FuSenglass, "Failure" is defined by the customer. For a chemical company, failure might be a hole in the bottle. For a perfume brand, failure is a slight loss of gloss.

The Acidic Range (pH 1 – 6):

- Visual Stability: Excellent. You can store vinegar (pH 3) or cola (pH 2.5) for 5 years, and the bottle will look brand new.

- Chemical Stability: Leaching occurs, but it is invisible. The risk here is regulatory (leached heavy metals), not aesthetic.

The Neutral Range (pH 6 – 8):

- Stability: Generally high. However, long-term storage of pure water can leach sodium, slowly raising the pH into the alkaline danger zone (the "Water Attack").

The Alkaline Danger Zone (pH > 9):

This is where concentration matters immensely.

- pH 8 – 10 (Weak Alkali): Examples: Baking soda solution, some soaps.

- Effect: Slow attack. Might take months to see a "ring" at the liquid line.

- pH 10 – 12 (Moderate Alkali): Examples: Ammonia cleaners, Alkaline water.

- Effect: Visible haze can appear in weeks, especially if warm. The glass loses its sparkle.

- pH 13 – 14 (Strong Alkali): Examples: Caustic Soda (NaOH), Bleach concentrate.

- Effect: Rapid destruction. In 4% NaOH (pH ~13.5), soda-lime glass can lose significant weight and turn completely opaque/white within 24 hours at elevated temperatures due to glass etching 6.

Concentration Threshold Matrix

| pH Range | Common Products | Soda-Lime Glass Status | Visual Signs of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 | Industrial Acids | Stable | None (unless HF is present). |

| 2.0 – 5.0 | Juices, Wine, Soda | Stable | None. Perfect clarity. |

| 7.0 | Water | Stable | None (potential internal pH drift). |

| 9.0 – 10.0 | Detergents, Hard Water | Caution | Slight "rainbow" effect over time. |

| 11.0 – 12.0 | Bleach, Ammonia | Vulnerable | Cloudiness, white film, loss of gloss. |

| > 13.0 | Drain Cleaner, CIP | Failure | Heavy etching, rough texture, material loss. |

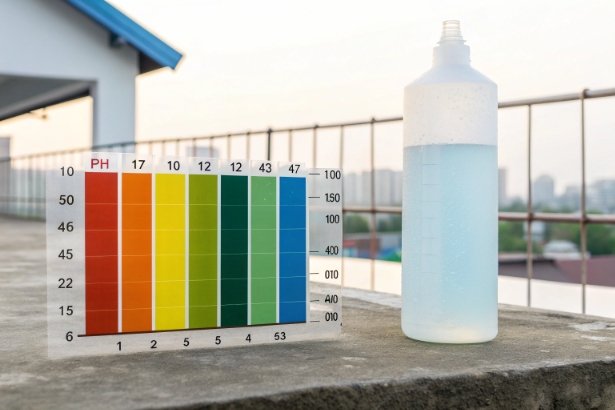

Concentration is bad, but when you add heat, it becomes catastrophic.

How do concentration and temperature work together to accelerate leaching during hot-fill, CIP, or dishwasher exposure?

In the chemistry of corrosion, $1 + 1 = 10$. Temperature multiplies the aggressiveness of the concentration, turning a manageable cleaning cycle into a bottle-destroying event.

Concentration and temperature act synergistically: higher concentration provides more attacking ions, while higher temperature provides the kinetic energy for those ions to overcome the activation energy barrier of the glass bonds. In processes like CIP or hot-fill, a high-concentration alkali that is safe at room temperature can cause severe etching when heated, as the reaction rate doubles for every 10°C increase.

The Multiplier Effect in Production

I have seen production managers try to speed up their cleaning lines by increasing the caustic concentration. Then, to be "sure," they turn up the heat. Then they call me asking why their bottles look scuffed.

The Arrhenius Multiplier:

Chemical reaction rates generally follow the Arrhenius equation 7.

- Concentration ($C$): Increasing NaOH from 1% to 2% doubles the number of attackers. Reaction rate increases linearly (roughly).

- Temperature ($T$): Increasing temp from 60°C to 80°C quadruples (or more) the reaction rate.

Real-World Scenario: The CIP Disaster

- Scenario A: 2% Caustic Soda at 20°C.

- Result: Glass is fine. Minimal etching.

- Scenario B: 2% Caustic Soda at 80°C.

- Result: Significant etching. The heat allows the abundant $OH^-$ ions to smash the Silica bonds.

- Scenario C: 0.5% Caustic Soda at 80°C.

- Result: Glass is often safer. Even though the heat is high, there are fewer attackers ("Soldiers") to do the damage.

Hot-Fill Leaching:

For acidic products (Hot-Fill 8 Juice), the synergy affects leaching.

- The heat opens the glass network (expansion).

- The acidity provides the proton exchange.

- The result is a "Leaching Spike" during the 30-minute cool-down period that can be equal to 1 year of storage at room temperature.

Synergy Impact Table

| Condition | Temp | Concentration | Corrosion Rate | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold / Dilute | 20°C | Low | 1x (Base) | Safe. |

| Hot / Dilute | 80°C | Low | 10x | Moderate risk (Dishwasher). |

| Cold / Conc. | 20°C | High | 5x | Moderate risk (Bleach storage). |

| Hot / Conc. | 80°C | High | 100x+ | Severe Damage. (Industrial CIP). |

You cannot control the chemistry of the universe, but you can control the specs of your purchase.

What test conditions and pass/fail criteria should buyers define to match real product concentration and shelf life?

Standard ISO tests use standard chemicals (water, HCl, NaOH). If your product is a proprietary mix, you need a custom validation plan.

Buyers should define a "Product-Specific Durability Test" where the glass is exposed to the actual product concentration at an elevated temperature (e.g., 50°C) for an accelerated period. Pass/fail criteria should include quantitative limits on "Alkali Release" (ISO 4802) for safety, and "Haze Increase" (< 2%) or "Visual Grading" for aesthetic acceptance.

Designing Your Validation Protocol

Don’t blindly trust a generic datasheet. As a ghostwriter for your QA strategy, here is the protocol I recommend to ensure your bottles survive your specific concentration.

1. The "Real Juice" Test (For Leaching):

- Medium: Your actual product (not just water).

- Condition: Fill bottles, cap them. Store at 40°C for 3 months (simulates ~1 year ambient).

- Measurement:

- pH Drift: Did the pH rise? (e.g., Max drift +0.5).

- Sensory: Taste test. Any "soapy" or "mineral" off-notes?

- Visual: Check for sediment (precipitation).

2. The "Super Wash" Test (For Returnables/CIP):

- Medium: Your exact detergent mix at 2x concentration (Safety Factor).

- Condition: Soak at your max process temperature (e.g., 85°C) for 24 hours.

- Measurement:

- Gravimetric: Weigh bottle before and after. Max loss < 50 mg.

- Visual: Inspect dried bottle under strong light against a black background. Criteria: Grade 0 (No visible haze).

3. The Standard Specs (For Purchasing):

Include these in your PO to filter out bad glass batches.

- Acid Resistance: DIN 12116 – Class S1 or S2.

- Alkali Resistance: ISO 695 9 – Class A2.

- Hydrolytic Resistance: ISO 4802 10 – HGB 3.

Buyer’s Pass/Fail Checklist

| Test Type | Simulates | Condition | Pass Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated Aging | Shelf Life | 50°C / 4 Weeks | No haze; pH drift < 0.2. |

| Soak Test | CIP Cycle | 80°C / 24 Hours in 4% NaOH | No visible etching (Grade 0). |

| Dishwasher Test | Home Use | 125 Cycles (IEC Detergent) | No permanent clouding. |

| ISO 695 | Material Quality | Boiling Alkali Mixture | Weight loss < 100 mg/dm². |

Conclusion

Concentration is the variable that turns a safe packaging material into a risky one. While acidic concentration is rarely a threat to soda-lime glass, alkaline concentration acts as a solvent for the bottle itself. By understanding the "Danger Zone" of pH 9+ and the synergistic multiplier of heat, you can set realistic test standards that ensure your FuSenglass bottles remain crystal clear and chemically secure for the life of your product.

Footnotes

-

Composition and properties of the most common commercial glass. ↩

-

The active species in acidic solutions that triggers ion exchange. ↩

-

The active species in alkaline solutions responsible for network dissolution. ↩

-

The fundamental chemical bond forming the backbone of the glass network. ↩

-

A silica-rich protective barrier formed during acidic attack. ↩

-

The chemical process where glass material is dissolved by strong bases. ↩

-

The formula calculating how temperature reaction rates multiply with heat. ↩

-

A packaging method where hot product sterilizes the container. ↩

-

Standard test method for glass resistance to boiling mixed alkalis. ↩

-

Standard for measuring hydrolytic resistance of glass surfaces. ↩