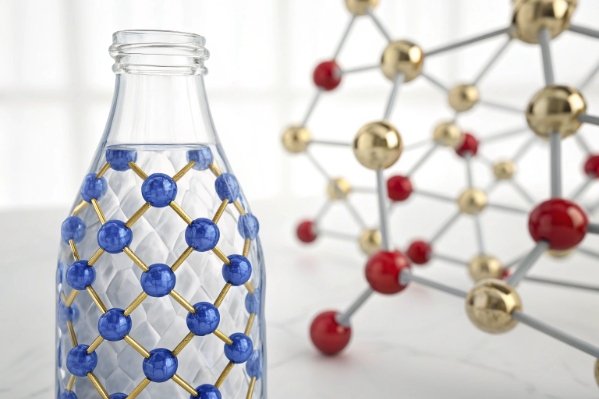

Glass corrosion ruins products and damages brand reputation. We must understand how alumina acts as a critical stabilizer to strengthen the glass network against harsh chemical environments.

Alumina acts as a powerful network intermediate, modifying the silica structure to close molecular gaps. It significantly stabilizes the glass matrix, reducing the mobility of alkali ions like sodium. This structural reinforcement directly improves the container’s resistance to both acidic attack (leaching) and alkaline corrosion (dissolution) during storage and washing.

Understanding the Role of Alumina in Glass Stability

At FuSenglass, we often encounter clients who view glass as an inert material that never interacts with its contents. While glass is chemically stable compared to plastics, it is not immune to corrosion. The secret to manufacturing a bottle that can withstand acidic fruit juices, carbonated beverages, or high-pH cleaning detergents lies in the precise formulation of the batch, specifically the alumina (Al₂O₃) content.

Alumina serves as a "network intermediate" 1 in the glass-making process. Standard container glass is primarily Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂), which forms the backbone. However, pure silica requires impossibly high temperatures to melt. To lower the melting point, we add fluxing agents like Soda Ash (Na₂O), but this creates a problem: it breaks the strong oxygen bridges in the silica network, creating "Non-Bridging Oxygens" (NBOs). These NBOs make the glass susceptible to water and chemical attack.

This is where Aluminum Oxide enters the equation. When we introduce Al₂O₃ into the melt, it consumes these weak NBOs and re-links the silica structure. It essentially "heals" the breaks caused by the fluxing agents. By re-establishing the connectivity of the glass network, alumina reduces the ability of water and other chemicals to penetrate the surface.

In my twenty years of experience overseeing production lines, I have seen that even a fractional percentage increase in alumina can drastically change a bottle’s performance. For industries like pharmaceuticals or premium spirits, where the liquid might sit in the bottle for years, this chemical durability is non-negotiable.

Key Functions of Alumina in Glass

| Function | Description | Impact on Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Network Formation | Acts as an intermediate oxide, bridging silica tetrahedra. | Increases structural integrity and hardness. |

| Ion Immobilization | Traps alkali ions (Na+) within the structure. | Prevents "blooming" or weathering on the glass surface. |

| Chemical Durability | Reduces solubility in water, acids, and alkalis. | Protects the product inside from contamination. |

| Thermal Stability | Lowers the coefficient of thermal expansion 2. | Reduces breakage during hot filling or pasteurization. |

| Viscosity Control | Increases viscosity at lower temperatures. | Helps maintain bottle shape during the forming process. |

Understanding the basic function of alumina is the first step. Now, we need to analyze exactly how it alters the atomic structure to stop chemical leaching.

What glass-network changes occur when Al₂O₃ increases, and how do they limit ion leaching in acidic and alkaline solutions?

Leaching contaminates sensitive formulations and alters flavor profiles. Alumina modifies the atomic geometry of the glass to lock dangerous ions firmly inside the silicate matrix.

Adding alumina transforms unstable Non-Bridging Oxygens (NBOs) into stable tetrahedral [AlO₄]⁻ groups. This structural tightening eliminates the open diffusion channels that alkali ions use to move. By blocking these pathways, alumina effectively prevents water and acids from extracting sodium and stops the silicate network from dissolving under high-pH alkaline conditions.

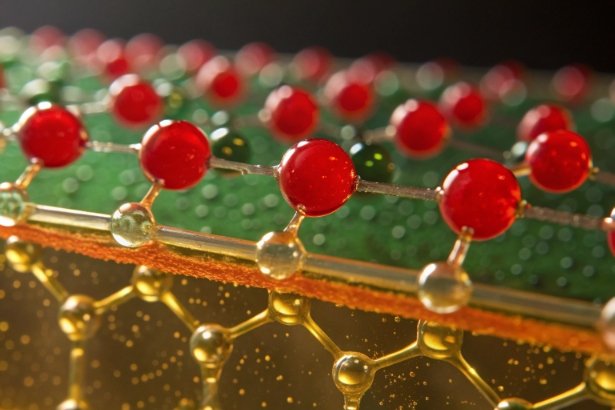

The Mechanism of Chemical Resistance

To understand why your glass packaging fails or succeeds, we have to look at the atomic level. In standard soda-lime glass without sufficient alumina, sodium ions (Na+) are loosely held in the "holes" of the silica network. When an acidic solution (like vinegar or fruit juice) touches the glass, hydrogen ions (H+) from the acid swap places with the sodium ions in the glass. This is called ion exchange, or leaching 3. The result is a silica-rich layer on the surface that can flake off or cloud the contents.

When we increase Al₂O₃, the aluminum atoms coordinate with four oxygen atoms to form a tetrahedron ([AlO₄]⁻). This negatively charged unit attracts the positively charged sodium ions. Instead of being loose wanderers, the sodium ions are now electrostatically bound to the aluminum structure for charge compensation. This "locks" the alkali ions in place.

In my technical discussions with quality control engineers, I emphasize that this is a dual-defense mechanism.

-

Acid Resistance: By binding the alkali ions tightly, alumina prevents the H+ ions from the liquid from swapping with the Na+ ions in the glass. If the exchange cannot happen, leaching is stopped.

-

Alkali Resistance: Alkaline solutions (like caustic soda used in bottle washing) attack the silica network directly, breaking the Si-O-Si bonds. The Al-O bond is much more resistant to this hydrolysis 4 than the Si-O bond (when modified by alkali). Therefore, a glass network enriched with alumina slows down the total dissolution of the glass surface.

However, the ratio is critical. The aluminum must be in the tetrahedral coordination to work this magic. If the ratio of alkali to alumina is off, aluminum might enter as a modifier with six oxygen neighbors ([AlO₆]³⁻), which does not provide the same stability. This is why our batch calculation at FuSenglass is precise to the decimal point.

Acid vs. Alkali Attack Mechanisms

| Attack Type | Mechanism | Role of Alumina (Al₂O₃) |

|---|---|---|

| Acid Attack | Ion Exchange: H+ ions from acid replace Na+ ions in glass. | Binds Na+ tightly for charge balance, preventing them from migrating out. |

| Alkali Attack | Network Dissolution: OH- ions break Si-O-Si bonds, dissolving the glass. | Strengthens the network bonds; Al-O bonds are more resistant to hydroxyl attack. |

| Water Attack | Hydrolysis: Water enters the network and leaches alkali. | tightens the network structure, reducing pore size and water diffusion rates. |

| Weathering | Atmospheric Moisture: Humidity reacts with surface alkali. | Reduces surface alkali availability, preventing white haze (blooming 5). |

We have established that alumina improves resistance, but manufacturing is a balancing act. We must ask: is there such a thing as too much alumina?

When can high alumina reduce durability or raise processing risk, and what Al₂O₃ range is typical for chemically durable container glass?

More alumina isn’t always better for production. Excessive amounts create severe melting challenges, increase energy costs, and introduce defects that threaten container integrity.

High alumina content drastically increases glass viscosity, forcing us to use higher melting temperatures which spikes energy consumption. If not strictly controlled, it causes devitrification (crystallization), creating "stones" in the glass. These stones are brittle stress points that weaken the bottle. The optimal range for standard chemically durable container glass is typically 1.5% to 2.5%.

The Risks of High Alumina Content

As a manufacturer, I constantly balance "product performance" with "manufacturability." While a scientist might want 10% alumina for supreme chemical resistance, a production manager knows that would be a nightmare for a standard soda-lime furnace.

The primary issue is viscosity. Alumina creates a "stiff" glass. As you increase the percentage of Al₂O₃, the temperature required to melt and refine the glass rises significantly. For every 1% increase in alumina, we might need to raise furnace temperatures by 10-20°C. This leads to higher fuel consumption and faster degradation of the furnace refractories. In a high-volume factory like FuSenglass, where we produce 30,000 tons annually, these energy costs are substantial.

Furthermore, high alumina content creates a risk of devitrification. This is when the glass tries to revert to a crystalline structure as it cools. If the glass composition is too rich in alumina relative to the other oxides, crystals (such as nepheline or albite) can form. We call these "stones 6." A stone is a defect; it has a different coefficient of thermal expansion than the surrounding glass. When the bottle cools or is pasteurized, the stress around that stone will cause the bottle to crack or explode.

There is also a chemical tipping point. If the molar amount of Al₂O₃ exceeds the molar amount of alkalis (Na₂O + K₂O), the "aluminum anomaly" occurs. The aluminum can no longer find enough alkali ions to charge-balance its tetrahedral structure. It switches coordination numbers, and the glass properties—including durability and density—can suddenly change in unpredictable ways.

Optimal Alumina Ranges by Glass Category

| Glass Category | Typical Al₂O₃ Range | Processing Characteristics | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Soda-Lime | 1.5% – 2.5% | Good workability, moderate melting temp. | Low risk. Ideal balance for food/bev. |

| High-Performance Soda-Lime | 2.5% – 4.0% | Higher viscosity, requires hotter furnace. | Increased fuel cost, risk of cords (streaks). |

| Pharmaceutical Amber | 3.0% – 5.0% | Specific formulation for UV and chemical protection. | Must control iron/sulfur ratio carefully. |

| Aluminosilicate | 15.0% – 25.0% | Extremely high melting point, specialized furnaces. | Very difficult to fine; high risk of stones. |

| Lead Crystal | < 0.5% | Very fluid, easy to cut and polish. | Low chemical durability (leaches lead). |

Now that we know the risks, let’s compare the different glass types available on the market to see which one fits your specific product needs.

How do soda-lime, borosilicate, and aluminosilicate bottles differ in alumina content and chemical resistance for food packaging and caustic cleaning?

Not all glass is equal. Different formulations suit specific needs, from cost-effective beverage bottles to high-end vials requiring extreme caustic resistance.

Soda-lime glass (1-2% alumina) offers moderate resistance suitable for most food and beverages. Borosilicate relies on boron for thermal shock but has lower resistance to alkaline attack. Aluminosilicate glass contains high alumina (up to 20%), offering superior physical strength and exceptional chemical durability against caustic cleaning agents, making it ideal for high-reuse systems or aggressive pharmaceuticals.

Comparative Analysis of Glass Types

Choosing the right glass composition is a strategic business decision. I often guide new clients away from expensive borosilicate if standard soda-lime with the right treatment can do the job. However, for specialized applications, the composition dictates performance.

Soda-Lime Glass (Type III):

This is the workhorse of the packaging industry. With an alumina content usually between 1.5% and 2.5%, it provides a "good enough" barrier for water, juice, beer, and standard cosmetics. It is chemically durable enough for single-use or limited-reuse cycles. However, if you subject it to repeated hot caustic washing (like in returnable milk or beer bottle schemes), the surface will eventually etch, creating a scuff ring.

Borosilicate Glass (Type I):

Famous for its thermal shock resistance (think Pyrex), this glass replaces much of the alkali and lime with Boron Oxide (B₂O₃). While it has excellent acid resistance (Hydrolytic Class 1 7), it is surprisingly vulnerable to alkali attack. Strong caustic detergents attack the boron network faster than they attack an alumina-reinforced network. Therefore, while it is the gold standard for injectable drugs (neutral glass), it is not always the best choice for bottles that will be washed with high-pH industrial cleaners repeatedly.

Aluminosilicate Glass:

This is the heavy hitter. It contains very little alkali and very high alumina (15-25%). This structure is incredibly tight. It resists the migration of ions almost entirely. It is used in high-performance applications like smartphone screens (Gorilla Glass) and specialized chemical containers. For packaging, it is rare due to the high cost, but for returnable bottles that undergo hundreds of caustic wash cycles, a modified soda-lime with higher alumina content acts as a bridge toward this performance.

Glass Composition and Resistance Matrix

| Glass Type | Alumina (Al₂O₃) | Acid Resistance | Alkali Resistance | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soda-Lime (Type III) | 1.5% – 2.5% | Good | Moderate | Food, Beverage, Cosmetic, Wine. |

| Treated Soda-Lime (Type II) | 1.5% – 2.5%* | Very Good | Moderate | Intravenous fluids, acidic chemicals. (Surface de-alkalized) |

| Borosilicate (Type I) | 2.0% – 6.0% | Excellent | Low to Moderate | Labware, Pharma Vials, Injectables. |

| Aluminosilicate | 15% – 25% | Excellent | Excellent | High-reuse returnables, severe chemical storage. |

You have selected your material. Now, how do you prove to your stakeholders and safety regulators that the bottles are safe?

Which qualification tests and standards (ISO 719/720 hydrolytic plus acid/alkali corrosion) should be specified to confirm bottle durability before mass purchase?

Trust but verify. Standardized testing ensures your packaging survives the supply chain and protects your brand from contamination liabilities.

Specify ISO 719/720 for hydrolytic resistance to measure water leaching and classify the glass type. For aggressive contents, demand ISO 695 (alkali resistance) and DIN 12116 (acid resistance). These tests quantify surface erosion and ion release, guaranteeing that the bottle meets strict safety and durability requirements before you commit to a mass order.

Essential Qualification Standards

In the B2B world, vague promises of "quality" mean nothing. We deal in certificates and data. When sourcing from China or anywhere else, you must include these specific ISO standards in your Quality Assurance (QA) 8 agreement.

Hydrolytic Resistance (ISO 719 / ISO 720 / USP <660>):

These are the most common tests. They simulate the effect of water on the glass over time.

-

ISO 719 9 (Grains Test): We crush the glass into grains and boil them in water. We then titrate the water to see how much alkali leached out. This determines the "Class" of the glass (HGB1 to HGB5).

-

ISO 720: Similar to 719 but uses autoclaving at higher temperatures (121°C).

-

Significance: If your bottle fails this, your product pH will shift, and sediment might form.

Acid Resistance (DIN 12116):

This test boils the glass in Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) for 6 hours. We measure the weight loss of the glass.

- Significance: Critical for acidic foods (pickles, tomato sauce) and many pharmaceuticals. A high weight loss means the glass is dissolving into your product.

Alkali Resistance (ISO 695 10):

The glass is boiled in a mixture of Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) and Sodium Carbonate. This is an aggressive test.

- Significance: This is vital for "returnable" fleets. If you plan to wash and refill your bottles, you need to know how many cycles they can endure before they look cloudy (scuffed). A bottle with higher alumina will generally show less weight loss in this test.

At FuSenglass, we provide reports for all these metrics. We recommend that our clients perform "validation batches"—ordering a smaller quantity to run through their specific filling and washing lines—before committing to the full 10,000 piece MOQ.

Testing Standards Breakdown

| Standard | Test Name | Methodology | What it Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 719 / 720 | Hydrolytic Resistance | Boiling grains/surface in water. | Alkali release (pH shift). Classifies Type I, II, III. |

| USP <660> | Surface Glass Test | Autoclaving filled bottles. | Suitability for pharma/parenteral use. |

| DIN 12116 | Acid Resistance | Boiling in 6N HCl for 6 hours. | Weight loss (erosion) in acidic environments. |

| ISO 695 | Alkali Resistance | Boiling in NaOH + Na₂CO₃. | Resistance to caustic washing/detergents. |

| ASTM C148 | Polariscopic Exam | Polarized light inspection. | Residual internal stress (annealing quality). |

Conclusion

Alumina is the unsung hero of glass packaging, providing the chemical backbone that protects your product. Balancing its content is the key to achieving a durable, safe, and cost-effective bottle.

Footnotes

-

Oxides like alumina that can act as either network formers or modifiers, strengthening the glass structure. ↩

-

A material property quantifying how much glass expands when heated, critical for thermal shock resistance. ↩

-

The extraction of soluble components from a solid material into a liquid, often referring to alkali ions leaving glass. ↩

-

A chemical breakdown reaction involving water, which can weaken the glass network over time. ↩

-

The formation of a hazy white film on glass surfaces caused by alkali leaching and reaction with humidity. ↩

-

Solid inclusions or crystals in glass that create stress points and potential failure sites. ↩

-

Glass quality standards defined by the US Pharmacopeia for pharmaceutical packaging. ↩

-

A systematic process used to ensure that products meet specified quality requirements. ↩

-

International standard specifying the test method for hydrolytic resistance of glass grains at 98°C. ↩

-

International standard for testing the resistance of glass to a boiling mixture of alkaline solutions. ↩