From high-acid citrus juices to phosphoric acid-rich colas, acidic beverages form a massive portion of the global bottling market. But does the pH level of your product silently conspire with heat to weaken your packaging?

Beverage acidity does not alter the glass’s Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), but it can accelerate "Stress Corrosion," a mechanism where acidic moisture attacks microscopic surface flaws, lowering the energy required for cracks to propagate during thermal shock.

Dive Deeper: The Chemistry of the Crack

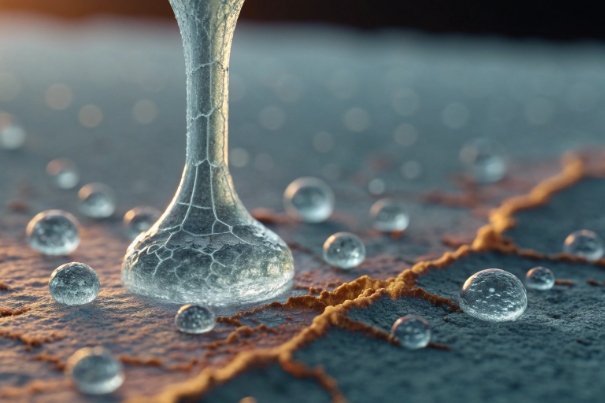

At FuSenglass, we frequently analyze why a bottle filled with water survives a thermal cycle that shatters a bottle filled with hot vinegar or juice. The answer lies not in the bulk expansion of the material, but in the microscopic chemical reactions occurring at the tip of surface flaws.

Glass is technically defined as a "brittle elastic solid." It fails when tensile stress stretches the atomic bonds at the tip of a crack until they snap. This is a physical process. However, environmental factors play a massive role. The phenomenon is known as Stress Corrosion Cracking or Static Fatigue.

While silica glass is famous for being chemically inert to most acids (except Hydrofluoric acid), the water content in beverages interacts with the glass surface. The presence of hydrogen ions (H+) and water molecules at the tip of a stressed crack can react with the Silicon-Oxygen (Si-O) network. This reaction "hydrolyzes" the bond, effectively snipping the atomic wire holding the glass together.

When you add heat (thermal stress) to this chemical attack, you create a "perfect storm." The heat widens the crack, allowing fresh acidic liquid to enter, and the chemical reaction lowers the stress threshold needed to extend the crack further.

The Acid-Stress Interaction Table

| Factor | Description | Effect on Glass Strength |

|---|---|---|

| CTE (Expansion) | Physical property of the silica lattice. | Neutral. Unchanged by pH. |

| Surface Flaws | Micro-scratches/Griffith Flaws 1. | Target. Acid attacks these weak points. |

| Stress Corrosion | Chemical attack on stressed bonds. | Accelerant. Speeds up crack growth. |

| Leaching | Removal of alkali ions (Sodium/Calcium). | Minor Risk. Can roughen surface over time. |

Now, let’s dissect the specific ways acidity and heat interact to challenge your packaging integrity.

Does beverage acidity change a glass bottle’s thermal expansion (CTE), or does it mainly affect cracking risk under temperature swings?

Procurement managers often ask if they need "special expansion glass" for lemonade or kombucha. The confusion stems from mixing up chemical resistance with thermal resistance.

Acidity has zero effect on the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), which remains fixed by the glass recipe. However, acidic environments lower the "fatigue limit" of the glass, meaning it requires less thermal stress to fracture an existing flaw than it would in a dry or neutral environment.

The Physics of the Crack Tip

To understand this, we must look at the Charles and Hillig theory of stress corrosion.

-

The Bond: Glass is held together by Si-O-Si bonds.

-

The Stress: When a bottle is heated or cooled rapidly, the surface enters tension. This tension pulls the Si-O bonds apart at the tip of a micro-crack.

-

The Attack: A water molecule (or hydronium ion from acid) inserts itself into this stretched bond.

-

The Rupture: The chemical reaction breaks the bond ($Si-O-Si + H_2O \rightarrow Si-OH + HO-Si$).

This reaction effectively "unzips" the glass at the molecular level. Since acids are aqueous (water-based), they facilitate this process. While strong acids can sometimes actually blunt cracks (by dissolving the tip), typical food acids (Citric, Malic, Phosphoric) in a high-stress thermal environment generally promote this "slow crack growth."

Therefore, a bottle might theoretically withstand 50 MPa of stress in a vacuum. But filled with acidic juice, it might fail at 40 MPa because the chemistry is helping the physics break the bond.

Material Property vs. Environmental Limit

| Property | Value for Soda-Lime Glass | Influence of Acidity (pH < 4.0) |

|---|---|---|

| CTE | $9.0 \times 10^{-6}/K$ | None (0%) |

| Young’s Modulus | 70-73 GPa | None (0%) |

| Tensile Strength | ~40-50 MPa (Practical) | Reduced (Can drop by 10-20% over time) |

| Crack Velocity | Variable | Increased (Subcritical crack growth 2 accelerates) |

How do acids + heat influence glass strength (surface leaching, stress corrosion) and make bottles more sensitive to thermal shock?

Beyond the crack tip, acids can alter the surface chemistry of the glass itself, especially during high-heat processing like hot-filling or retorting.

Combined with heat, acids accelerate the leaching of sodium ions from the glass surface ("de-alkalization"). While this can theoretically strengthen glass by creating a silica-rich layer, irregular leaching can create surface porosity that acts as new stress concentrators, making the bottle more sensitive to thermal shock.

The Leaching Mechanism (De-alkalization)

Standard soda-lime glass contains about 13-15% Sodium Oxide ($Na_2O$). Sodium is loosely held in the network.

-

The Reaction: When hot acid touches the glass, Hydrogen ions ($H^+$) from the acid swap places with Sodium ions ($Na^+$) in the glass. ($Si-O-Na + H^+ \rightarrow Si-O-H + Na^+$).

-

The Result: The sodium leaches out into the liquid (usually at harmless ppm levels). The glass surface becomes a "silica-gel" layer.

The Double-Edged Sword

-

The Benefit: A uniform silica-rich layer has a lower expansion coefficient than the bulk glass. This can actually put the skin in compression, slightly strengthening it (similar to a weak chemical strengthening 3).

-

The Danger (Sensitivity): If this reaction happens unevenly—due to surface coatings, washing residues, or "weathering" (bloom) in the warehouse—it creates a microscopic "crazed" or porous surface. These micropores are essentially millions of new Griffith flaws.

When thermal shock 4 hits (e.g., cooling a hot bottle):

-

Fresh Glass: Has random flaws.

-

Leached/Corroded Glass: Has a network of surface compromised zones.

-

Outcome: The "aged" or chemically attacked bottle fails at a lower $\Delta T$ (temperature differential) than a new one. This is why reusable bottles (returnable glass) for acidic sodas eventually must be retired; the acid + wash cycles fatigue the glass.

Impact of Temperature on Leaching

The rate of this chemical attack doubles for every 10°C rise in temperature.

-

Cold Storage: Negligible effect.

-

Pasteurization (60°C): Moderate effect.

-

Retort (121°C): Rapid leaching. (This is why Type I Borosilicate 5 is used for acidic pharma drugs, to prevent pH shifts and glass flaking).

Which acidic drink processes create the highest thermal-stress risk (hot-fill, pasteurization, rapid cooling, cold-chain), and how should filling temperatures be set?

The beverage type dictates the process, and the process dictates the risk. High-acid foods often rely on heat for preservation, pushing the glass to its limits.

Hot-filling of high-acid juices (pH < 4.6) poses the highest immediate risk due to the sharp $\Delta T$ shock at the moment of filling and the subsequent vacuum stress. Pasteurization of carbonated acidic drinks poses a secondary risk due to internal pressure spikes combined with thermal expansion.

1. Hot-Fill (Juices, Isotonics, Teas)

-

The Process: Liquid is heated to 85°C–92°C and poured directly into the bottle.

-

The Acid Factor: High acidity (e.g., Lemon Juice pH 2) is aggressive.

-

The Thermal Risk:

-

Mitigation:

-

Pre-heat bottles to 50°C-60°C to lower the $\Delta T$.

-

Use Heavy-Weight glass designs to resist the vacuum implosion (paneling).

-

2. Tunnel Pasteurization (Beer, Cider, CSDs)

-

The Process: Filled cold, then sprayed with hot water to reach ~60 PU (Pasteurization Units 7).

-

The Acid Factor: Phosphoric or Citric acid + Carbonation ($CO_2$).

-

The Thermal Risk:

-

Pressure: Heat expands the gas. Acidic sodas can reach 80-90 psi inside the bottle during pasteurization.

-

Stress Corrosion: The heat + acid + pressure works to propagate any bottom cracks.

-

-

Mitigation:

-

Strict adherence to Headspace guidelines (min 6% volume) to allow expansion.

-

Glass rated for internal pressure (typically 12-16 bar).

-

3. Cold Aseptic Filling

-

The Process: Sterilized cold liquid into sterilized cold bottles.

-

The Risk: Lowest thermal stress.

-

The Acid Factor: Only long-term storage leaching is a concern.

-

Benefit: Ideal for lightweight glass as it avoids the thermal shock of hot-fill.

Process Risk Hierarchy

| Beverage | pH | Process | Thermal Risk | Acid Risk | Recommended Glass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemon Juice | ~2.0 | Hot Fill (90°C) | Extreme | High | Heavyweight, Pre-heated |

| Cola | ~2.5 | Cold Fill + Carb | Low | Med | Standard Pressure Ware |

| Cider | ~3.5 | Pasteurize (60°C) | High | Med | Pressure Rated + $\Delta T$ |

| Tomato Sauce | ~4.2 | Hot Fill 8 (85°C) | High | Low | Wide Mouth Jar |

What bottle specs and validation tests should brands request for acidic beverages (thermal shock/cycling, internal coating compatibility, migration, and stress inspection)?

If you are bottling lemon juice or vinegar, you cannot simply buy a "standard" bottle and hope for the best. You need validation that the glass won’t degrade or crack under the specific chemical-thermal load.

Brands should mandate ASTM C147 Thermal Shock testing to verify $\Delta T$ resistance, Hydrolytic Resistance testing (USP Type III) to ensure minimal leaching, and Internal Pressure testing for carbonated acidic drinks.

1. Thermal Shock Testing (ASTM C147)

For hot-filled acidic products, this is the primary pass/fail metric.

-

Protocol: Heat bottle, plunge into cold water.

-

Requirement: Even if standard ware is rated for $\Delta T$ 42°C, hot-fill lines should demand a QC target of $\Delta T$ 50°C or 60°C to provide a safety margin against the "stress corrosion" effect of the acid.

2. Hydrolytic Resistance (Alkali Release)

This measures how much the glass reacts with the liquid.

-

Grades:

-

Type I (Borosilicate): Zero leaching. Best for pharma/lab.

-

Type II (Treated Soda-Lime): Sulfur-treated surface to neutralize alkali. Good for aggressive liquids.

-

Type III (Standard Soda-Lime): Standard for food/bev.

-

-

Test: Boil grain glass in water/acid and titrate the alkali released. For ultra-acidic or sensitive products, verify Type III limits are met comfortably.

3. Internal Surface Inspection

-

Visual: Check for "Weathering" (white haze) inside the bottle before filling.

-

Risk: Weathered glass has a pre-corroded surface that will leach rapidly and fail under thermal stress.

-

Action: Ensure bottles are stored dry and not for longer than 6 months before use.

Buyer’s Quality Spec Sheet

| Specification | Standard | Target for Acidic Beverages | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Shock | ASTM C147 10 | $\Delta T \ge 50°C$ | Buffers against stress corrosion failures. |

| Hydrolytic Resistance | ISO 719 | HGB 3 or better | Prevents flavor changes / glass degradation. |

| Internal Pressure | ISO 7458 | > 12 Bar (if carbonated) | Acid + Heat + CO2 = High Stress. |

| Wall Thickness | Min Spec | > 1.8mm (Body) | Prevents vacuum collapse (paneling). |

Conclusion

While the acidity of a beverage does not rewrite the laws of physics regarding the glass’s thermal expansion coefficient, it actively conspires with thermal stress to exploit the material’s weaknesses. Through the mechanism of stress corrosion, acidic liquids lower the energy threshold for crack propagation. For brand owners, this means that hot-filling a high-acid juice is a more delicate operation than filling water. By increasing your thermal shock safety margins ($\Delta T$), ensuring proper glass storage to prevent weathering, and pre-heating bottles during production, you can neutralize this chemical threat.

Footnotes

-

Microscopic flaws on the surface of brittle materials that significantly reduce their fracture strength. ↩

-

The slow extension of a crack in a material under stress, accelerated by corrosive environments. ↩

-

A process of strengthening glass by replacing smaller ions with larger ones on the surface. ↩

-

Failure of a material caused by sudden temperature changes, creating expansion/contraction stress. ↩

-

A type of glass known for its high resistance to thermal shock and chemical corrosion. ↩

-

A pressure lower than atmospheric pressure, created when hot liquid cools inside a sealed container. ↩

-

A unit of measurement quantifying the total heat exposure during the pasteurization process. ↩

-

A filling method where hot liquid sterilizes the container, requiring high thermal resilience. ↩

-

United States Pharmacopeia standards for glass containers used in pharmaceutical packaging. ↩

-

Standard test methods for internal pressure strength of glass containers. ↩