Inconsistent wall thickness, subtle "settle waves," or baffling breakage rates on the filling line often trace back to a single culprit: poor thermal management in the glass factory. Is your manufacturer merely melting sand, or are they mastering the precise physics of viscosity?

Controlling the forming temperature window requires a synchronized thermal strategy—from the forehearth’s conditioning zones to the mold cooling airflow—to maintain the glass within a narrow viscosity range (typically $10^3$ to $10^7$ Poise), ensuring the "gob" flows perfectly without slumping or freezing prematurely.

Dive Deeper: The Viscosity-Temperature Relationship

At FuSenglass, we consider temperature control to be the "heartbeat" of production. If the rhythm is off, the product dies. The concept of the "Forming Window" is not just a suggested temperature range; it is a rigid physical law dictated by the viscosity of the molten glass.

Glass does not have a melting point like ice; it has a viscosity curve 1. As it cools, it thickens.

-

Too Hot (Low Viscosity): The glass is too runny. It flows too fast in the mold, causing uneven wall distribution (thin bottoms/thick shoulders) and deformation after the bottle leaves the mold because the skin isn’t hard enough to support the shape.

-

Too Cold (High Viscosity): The glass is too stiff. It refuses to flow into the intricate designs of the mold, resulting in "short finishes" (incomplete rims), wrinkles, and "checks" (cracks) caused by the stress of trying to force a solidifying material to move.

The "Window" is the sweet spot between these two extremes. For standard soda-lime glass 2, this is typically between 1100°C (Gob delivery) and 700°C (Deflection/Release). Keeping the glass inside this window while it moves at high speed through metal molds is the ultimate challenge of glass engineering.

The Viscosity Scale (The "Log" Scale)

| Viscosity State | Viscosity (Poise) | Approx Temp (°C) | Physical Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point | $10^2$ | ~1450°C | Liquid honey. Used for refining/removing bubbles. |

| Working Point | $10^4$ | ~1050°C | The Gob. Soft taffy. Ready to be cut and loaded. |

| Littleton Softening Point | $10^{7.6}$ | ~720°C | Shape Hold. The bottle can stand up but is still soft. |

| Annealing Point | $10^{13}$ | ~550°C | Rigid solid. Stress relief zone. |

| Strain Point | $10^{14.5}$ | ~500°C | Completely solid. |

Now, let’s trace the thermal journey of a bottle and how we enforce strict controls at every stage to prevent defects in your packaging.

What does the “forming temperature window” mean in bottle production, and how is it linked to glass viscosity?

Many buyers assume that if the furnace is hot, the bottles will be fine. They fail to realize that a deviation of just 5°C at the feeder can alter the glass viscosity enough to change the bottle’s weight distribution and internal pressure resistance.

The "forming temperature window" defines the precise thermal range where the glass viscosity allows for proper loading, forming, and extraction. It is inextricably linked to viscosity because glass is a thermoplastic material; temperature controls how "stiff" or "runny" the material is at every millisecond of the forming cycle.

The Working Range Index (WRI)

The length of this "window" depends on the chemical composition of the glass. We call this the Working Range Index (WRI).

-

Long Glass: Has a wide temperature gap between the Working Point and Softening Point. It sets slowly, giving the machine operators more time to shape complex designs.

-

Short Glass: Sets very quickly. It requires higher machine speeds and more precise cooling.

For our clients, this matters because it dictates design feasibility. A complex embossed perfume bottle might require a "longer" glass or a hotter forming window to ensure the detail is filled before the glass freezes. A high-speed beer bottle line uses "shorter" thermal settings to maximize output speed.

If we miss the window:

-

Viscosity Drift: If the gob is 10°C hotter than the set point, its viscosity drops. It loads into the blank mold too fast, creating a "settle wave" (a visible ripple in the wall) or a thin neck.

-

Thermal Memory: Glass remembers its thermal history. If one side of the gob is colder than the other (thermal inhomogeneity), the cold side will be thicker (stiff) and the hot side thinner (stretchy). This creates "wedged" bottoms that fail under pressure.

Impact of Viscosity Deviations

| Defect | Cause (Viscosity/Temp) | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Thin Walls / Run-outs | Too Hot / Low Viscosity | Glass stretches too easily under gravity or blow pressure. |

| Wrinkles / Laps | Too Cold / High Viscosity | Glass skin freezes before it fully contacts the mold; folds over itself. |

| Checks (Cracks) | Thermal Shock (Cold Mold) | Hot glass hits a cold mold, surface freezes instantly and cracks. |

| Blisters / Seeds | Furnace Temp Fluctuations | Re-boil of gases due to unstable melting temps. |

How do furnace, forehearth, and feeder settings control gob temperature consistency and reduce variation?

The journey from the melting tank to the forming machine is critical. The glass must transition from a turbulent 1450°C liquid to a homogenous, thermally stable 1100°C "gob" without developing cold streaks or hot spots.

The forehearth and feeder act as the thermal conditioning system, utilizing multi-zone heating and cooling to deliver a "gob" with a thermal homogeneity of ±1°C. This ensures that every single drop of glass behaves exactly the same way when it hits the machine.

The Forehearth: The Conditioning Tunnel

The furnace melts the glass, but the Forehearth 3 prepares it. Think of the forehearth as a long, refractory-lined canal that connects the furnace to the machine. As the glass flows down this canal, we must cool it down from melting temp ($10^2$ Poise) to working temp ($10^3$ Poise).

But we can’t just let it cool naturally, or the sides would be cold (stiff) and the center hot (runny).

-

Zonal Control: We use multiple heating and cooling zones (Zone 1, 2, 3) equipped with gas burners and cooling winds.

-

The Goal: To ensure the temperature cross-section of the glass stream is identical. The center of the stream must be the same temperature as the edges. This is "Thermal Homogeneity."

The Feeder and Plunger

At the end of the forehearth is the Feeder Bowl. Here, a ceramic plunger pushes the glass through an orifice ring to form the "gob."

-

Tube Rotation: A revolving tube stirs the glass gently to mix out any remaining temperature gradients.

-

Plunger Action: The mechanical stroke determines the gob shape. If the glass temperature varies here, the gob weight will fluctuate. A hotter gob flows faster, creating a heavier bottle; a colder gob flows slower, creating a lighter bottle.

Critical Control Settings

| Component | Function | Critical Parameter | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rear Forehearth | Bulk Cooling | Cooling Wind / Damper | Drop temp from 1350°C to 1200°C |

| Front Forehearth | Homogenizing | Burner/Cooling Balance | Equalize Core vs. Skin Temp |

| Feeder Bowl | Final Conditioning | Tube Height / Rotation | ± 1°C Stability |

| Orifice Ring | Gob Shaping | Ring Temperature | Uniform flow release |

Which IS machine and mold cooling parameters keep forming temperatures stable and prevent defects like checks, wrinkles, and thin walls?

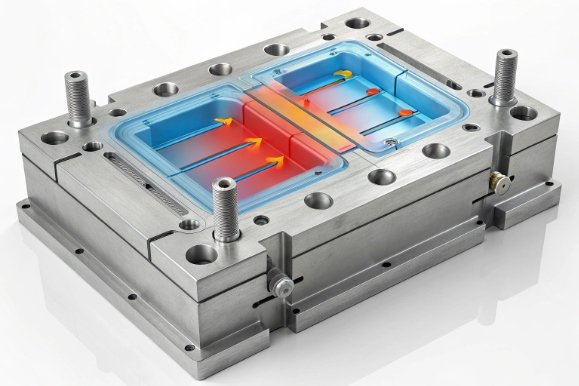

Once the gob enters the Individual Section (IS) machine 4, the clock starts ticking. We have milliseconds to remove enough heat to turn the red-hot blob into a rigid bottle, but not so much that we cause thermal shock.

Machine stability relies on the precise balance of "Mold Cooling Wind" (external airflow) and "Swabbing" (lubrication), coupled with strictly timed mechanical cycles (Time Index). This balance prevents the molds from overheating (sticking) or overcooling (checking).

The Heat Exchange Equation

The mold is essentially a heat exchanger. It absorbs heat from the glass and dissipates it into the air.

-

Glass Temp: Enters at ~1100°C.

-

Mold Temp: Must be maintained between 400°C and 500°C.

-

Cooling Air: High-velocity air is blown through channels in the mold (Vertiflow or Stack Cooling).

Managing the "Goldilocks" Zone

-

The "Blank" Side (First Stage):

-

Here the gob is formed into a parison 5 (a test-tube shape).

-

Risk: If the blank mold is too hot, the glass sticks to the metal (drag marks). If too cold, the skin freezes too fast, causing "settle waves" (ripples).

-

Control: Axial Mold Cooling. We adjust the duration and pressure of the cooling wind for each individual cavity.

-

-

The "Blow" Side (Final Stage):

-

The parison is blown into the final bottle shape.

-

Risk: Uneven cooling here leads to stress concentration 6. If one side of the mold cools faster, the bottle will lean or have uneven wall thickness ("dog bone").

-

Control: 360-degree Cooling. Ensuring air flows evenly around the entire shape.

-

-

Swabbing (Lubrication):

-

Operators manually or automatically apply a graphite-oil lubricant to the molds.

-

Purpose: Helps the glass slide and transfer heat.

-

Danger: Too much swab ("dirty ware") insulates the mold, trapping heat. Too little causes sticking and checks.

-

Troubleshooting via Cooling Parameters

| Defect | Thermal Cause | Machine Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Check (Crack) | Mold too cold (Thermal Shock) | Reduce Cooling Wind / Increase Cycle Speed |

| Stuck Ware | Mold too hot (Fusion) | Increase Cooling Wind / Check Swab |

| Lean / Bent Neck | Uneven heat removal | Check Cooling Balance L/R |

| Crizzled Surface | Over-cooled surface skin | Reduce Blank Cooling |

How can manufacturers monitor, record, and prove temperature-window control to B2B buyers?

Trust is good, but data is better. A B2B buyer should not just ask "Do you control temperature?" but "Show me the temperature curves."

Modern factories utilize Closed-Loop Process Control systems, including infrared pyrometers for continuous gob monitoring, automatic gob weight control loops, and hot-end rejectors that physically kick out bottles that fall outside the thermal profile.

The Toolkit of Verification

At FuSenglass, we employ a "Sensor-to-Data" approach. We don’t rely on an operator looking at the color of the glass. We rely on calibrated instruments.

-

Infrared Pyrometers (Gob Monitoring):

-

Sensors point directly at the falling gob.

-

Function: Measures the exact temperature of every single gob cut.

-

Feedback: If the temp drifts outside the ±2°C limit, the system alarms the furnace operator immediately.

-

-

Automatic Gob Weight Control (AGC):

-

Function: A weigh scale periodically checks a hot bottle. The data is fed back to the feeder.

-

Loop: If the bottle is too heavy (glass is too hot/fluid), the needle automatically adjusts to restrict flow. This indirectly confirms thermal stability.

-

-

Hot End Coating Monitoring:

-

The "Hot End Coating" (Tin Oxide) only bonds to glass within a specific temperature range (typically 500°C – 600°C).

-

Validation: If the coating thickness 7 is consistent, it proves the bottle exit temperatures were consistent.

-

-

Batch Traceability:

- All this data is logged against the "Batch ID." If you find a defect in the market, we can pull the thermal logs from that specific hour of production to see if a temperature excursion occurred.

Buyer’s Quality Audit Checklist

| Checkpoint | Tool/Method | What to Ask For |

|---|---|---|

| Gob Temp | IR Pyrometer 8 Log | "Show me the trend graph for the last 24 hours." |

| Mold Temp | Handheld Pyrometer | "How often do operators measure manual mold temps?" |

| Weight Stability | AGC Data Log | "What is your CpK 9 for bottle weight?" |

| Thermal Homogeneity | 9-Point Grid Test | "Do you test forehearth thermal homogeneity?" |

Conclusion

Controlling the forming temperature window is the difference between a glass bottle that acts as a robust vessel and one that is a fragile liability. By mastering the physics of viscosity through precise furnace conditioning, balanced mold cooling, and rigorous data monitoring, FuSenglass ensures that every bottle we produce is formed in that perfect "sweet spot" of thermal equilibrium.

Footnotes

-

A graph showing the relationship between temperature and the flow resistance of glass. ↩

-

The most common type of glass used for containers, requiring specific thermal controls. ↩

-

A refractory-lined channel that conditions molten glass temperature before forming. ↩

-

The standard machine used for mass-producing glass containers using compressed air. ↩

-

A preliminary glass shape formed in the blank mold before final blowing. ↩

-

A localized area where stress accumulates, increasing the risk of structural failure. ↩

-

Measurement of the protective layer applied to hot glass to prevent scratching. ↩

-

A non-contact thermometer used to measure high temperatures in glass manufacturing. ↩

-

A statistical metric that indicates how well a process is performing within limits. ↩