Broken bottles do not only waste glass. They ruin cartons, soak labels, and trigger chargebacks. A small packaging weakness can explode into a full-lane loss.

Reduce breakage by stopping three enemies: glass-to-glass contact, pallet instability, and uncontrolled shock and vibration. Build one pack-out system, then prove it with distribution tests before scale.

Why transport breakage happens, even when bottles pass factory QC?

Breakage is usually a packaging system failure

Glass bottles are strong in compression, but weak at the surface. Transport adds repeated small hits, not only one big drop. Those hits create micro-damage, then one impact finishes the crack. That is why a shipment can look fine at receiving, then show breakage during depalletizing.

Most breakage routes share one of these triggers:

- Contact damage: bottle-to-bottle or bottle-to-carton rubbing under load.

- Shock: drops, fork impacts, clamp-truck squeeze, curb hits, and hard set-down.

- Vibration fatigue: long truck routes, rail, sea containers, and rough roads.

- Compression collapse: cartons lose strength from humidity, overhang, or poor unitizing.

So the best strategy is not “more padding” everywhere. The best strategy is to control the energy path from the truck floor to the glass surface.

Start by locking the pack-out fundamentals

A strong pack-out system has five simple rules:

1) Each bottle is separated, so no glass touches glass.

2) The case has no free movement, so bottles cannot gain speed inside the box.

3) The pallet has no overhang, so box compression strength is not wasted.

4) The unit load has high friction between layers, so it does not shear during braking.

5) The wrap and corner support protect edges, so cartons keep their compression strength.

This approach is practical because it uses the parts you already buy: carton grade, divider type, pallet, and unitizing materials.

Use a hazard-to-fix map so teams move fast

When breakage happens, the pattern usually points to one cause. The fastest teams do not guess. They map damage to the likely hazard and change one variable at a time.

| Shipping hazard | Common symptom | Where it shows | Packaging lever that works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibration + rubbing | scuffs, label wear, later breaks | bottle shoulder and sidewall | dividers + snug fit + anti-slip layers |

| Edge drops / handling shock | broken necks, heel chips | top corners and pallet edges | corner boards + top cap + better drop performance |

| Compression overload | crushed cases, base cracks | bottom layers | no overhang + stronger board + column stacking |

| Shear during braking | leaning pallets, broken corners | pallet edges | anti-slip sheets + higher containment force |

| Humidity | soft boxes, collapsed stacks | warehouses, sea routes | moisture-resistant board + stretch hood |

Now the rest of this article goes deeper into each part of the solution. The goal is simple: fewer breaks without adding unnecessary cost.

If the pack-out is designed like a system, even lightweight bottles can ship safely.

Which cartons, dividers, and pallets minimize vibration and shock?

Small changes in cartons and dividers can cut breakage fast. Many brands focus on bottle strength, but transport failures often start with box strength and internal separation.

Use strong corrugated cases with tight internal fit, add dividers that prevent contact, and choose pallets that stay flat and square. The best designs reduce movement, not only add cushioning.

Cartons: strength, fit, and moisture behavior

Carton performance depends on board grade, design, and humidity. A box that tests strong in a dry lab can lose strength in a wet warehouse. So carton specs should match your lane:

- For long export routes, double-wall board often pays back.

- For short domestic routes, a well-designed single-wall case can be enough if unitizing is strong.

- A tight fit reduces internal impacts. Empty headspace inside the case is a breakage multiplier.

A simple rule works well: if bottles can “clink” in the closed case, the case needs redesign.

Dividers and inserts: stop contact and stop acceleration

Dividers do two jobs. They separate bottles and they slow impacts. Cell partitions are common and cost-effective. Molded pulp is stronger at cushioning and can reduce vibration transfer. Honeycomb and corrugated inserts can also add stiffness for stacking.

Divider selection should match the failure mode:

- If you see rubbing scuffs, use partitions that prevent side contact and reduce movement.

- If you see neck breaks, add top pads or neck support features.

- If you see heel chips, add bottom pads and reduce drop height inside the case.

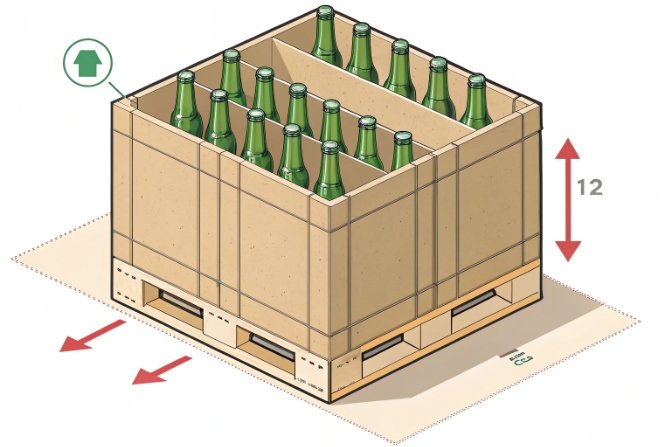

Pallets: flatness, stiffness, and overhang control

A strong case still fails on a weak pallet. Watch these pallet risks:

- Overhang reduces carton compression strength and crushes corners.

- Broken deck boards create point loads that crack heel areas in bottom-layer bottles.

- Flexible pallets amplify vibration and cause rocking.

Block pallets can offer better stability in some lanes. Stringer pallets can be fine if quality is controlled. The key is consistency and flatness.

| Component choice | Best for | Main benefit | Watch-out |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-wall case (strong grade) | short, dry lanes | low cost, good efficiency | loses strength in humidity |

| Double-wall case | export, humid lanes | high compression margin | more cost and weight |

| Corrugated cell dividers | most standard packs | prevents glass contact | must fit tight to avoid rattle |

| Molded pulp trays | premium and long lanes | cushioning + separation | size tooling and storage volume |

| Plastic crate (returnable) | closed-loop logistics | high protection, reuse | reverse logistics cost |

| Quality pallet (no overhang) | all lanes | protects carton corners | needs discipline at warehouse |

A practical implementation is to set a “pack-out standard” per lane. I have seen breakage drop when one brand stopped mixing pallet types and stopped allowing overhang. That change did not touch the bottle at all. It only stabilized the load.

When carton, divider, and pallet work together, vibration becomes less damaging because bottles do not hit each other and cases do not collapse.

Do corner boards, stretch or shrink, and anti-slip sheets help?

Unitizing looks simple until a truck brakes hard and the load shifts. Most pallet failures are not vertical. They are sideways shear and corner collapse.

Yes. Corner boards protect box edges, stretch or shrink containment prevents shear, and anti-slip sheets raise friction between layers. Together they keep compression strength and stop pallet lean.

Corner boards: protect compression strength where it matters

Carton corners carry most of the stacking load. When corners crush, cases collapse. Corner boards spread load and protect edges from strap and wrap pressure. They also help keep the load square.

Corner boards help most when:

- cases are tall and column-stacked,

- warehouses are humid,

- pallets face clamp trucks or tight handling.

Stretch wrap and shrink: containment force and lane matching

Wrap is not only “tight.” It is a controllable force. Too little force allows shifting. Too much force can crush cases. The goal is stable containment with minimal box damage.

Stretch wrap works well when applied with consistent pre-stretch and a defined wrap pattern. Shrink hood or shrink wrap can add excellent stability, especially for export lanes, because it reduces layer-to-layer movement.

A strong setup includes:

- a top cap sheet to bind the top layer,

- consistent wrap overlap,

- stable containment force targets,

- edge protection where wrap bites into corners.

Anti-slip sheets and tier sheets: friction is a breakage reducer

Anti-slip interlayers increase friction between layers. That reduces shear during braking and forklift turns. Tier sheets also spread load and protect cases from pallet deck defects.

For glass, anti-slip is often a low-cost win because it reduces micro-movement. Less micro-movement means less scuffing and fewer delayed cracks.

| Unitizing tool | What it improves | When it is most valuable | Common mistake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corner boards | corner crush resistance | high stacks, humid lanes | too short boards that miss the bottom layers |

| Top cap sheet | load tying and protection | any wrapped pallet | skipping it to save seconds |

| Stretch wrap | shear control | domestic lanes | random wrap patterns by operator |

| Shrink hood | strong unit stability | export and long storage | heat damage to weak cartons if poorly tuned |

| Anti-slip sheet | layer friction | braking, rough roads | using it without controlling moisture |

| Straps | handling robustness | clamp or long export | over-tension that crushes corners |

A stable pallet is a safety feature. It protects people and product. It also reduces claim rates. The best results come when unitizing is treated like a spec, not a warehouse habit.

How does bottle orientation and layer pattern matter?

Many teams copy a stacking pattern from another product and assume it is fine. Glass is less forgiving. Pattern choice can decide whether cartons crush or stay strong.

Orientation and layer pattern control load paths and movement. Column stacking usually protects carton compression strength. Interlock patterns can add stability but often reduce compression performance unless tier sheets and anti-slip are used.

Bottle orientation inside the case

Most glass bottles ship upright in cases. That supports predictable load paths through the carton and dividers. It also keeps closures from bearing side loads.

Inside the case, the key is symmetry and tightness:

- Bottles should sit centered in cells.

- Neck and shoulder clearance should be controlled, so they do not hit the box on drops.

- Bottom pads can protect heels during shock.

For some specialty packs, bottles ship horizontally. That can work, but it needs strong inserts because side loads rise and rubbing risk rises.

Layer pattern: column stack vs interlock

Column stacking aligns boxes directly over boxes. This preserves box compression strength. For glass, this often reduces bottom-layer failures. It also creates a clean load path down to the pallet.

Interlock patterns can improve pallet stability in some cases, but they interrupt the load path. That can reduce effective compression strength and crush corners. Many glass shippers use column stack plus anti-slip sheets to get the best of both worlds: strong compression and high friction.

Pallet edge rules: overhang and edge protection

No overhang is a strict rule for glass. Even small offsets expose corners to crush and reduce compression strength. Edge protection also matters because impacts happen at pallet edges first.

| Design choice | What it changes | Best use case | Risk if done wrong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Column stacking | strong vertical load path | high stacks, glass | needs anti-slip to resist shear |

| Interlock stacking | lateral stability | lighter loads, short stacks | can crush corners in heavy glass |

| Anti-slip between layers | reduces shear | any braking-heavy lane | loses value if wet and dirty |

| Tier sheets | spreads load | weak pallets or heavy cases | wrong sheet size causes edge exposure |

| Upright bottle orientation | stable load path | most wine and spirits | needs good divider fit |

| Horizontal bottle orientation | low height packs | gift packs and special designs | higher rubbing and side impact risk |

A simple way to choose is to match the pattern to the dominant hazard. If compression is the big risk, choose column stack. If shear is the big risk, add anti-slip and increase containment, not a weaker load path.

In practice, the safest configuration for glass is often column stack, no overhang, tier sheets, anti-slip, and a controlled wrap recipe.

What ISTA and ASTM tests simulate real shipping hazards?

Breakage reduction becomes real when the pack-out is proven in a test lab. A test also prevents internal debate. It turns opinions into data.

Choose ISTA or ASTM distribution simulation based on your shipping channel. Use ISTA 3A for parcel shipments, ISTA 3E for unitized pallet loads, and ASTM D4169 when you need a flexible schedule-based plan tied to distribution cycles.

Pick the test family that matches the lane

Shipping hazards depend on channel:

- Parcel delivery has high drops and rough handling.

- LTL and mixed freight has more impacts and stacking variability.

- Full truckload has long vibration exposure and braking shear.

- Export adds humidity, long storage, and port handling.

So one test does not fit all. The test plan should match the lane that creates the most claims.

Common ISTA choices for bottle shipments

ISTA procedures are widely used for general simulation:

- ISTA Procedure 3A for parcel delivery system shipments 1 is a common starting point when you ship single cases by parcel.

- ISTA Procedure 3E for similar packaged-products in unitized loads 2 is designed for palletized loads moving in full truckload-style distribution.

ISTA is useful when you want a recognized “pass” label for a given channel type.

Common ASTM choices for bottle shipments

ASTM gives you building blocks:

- ASTM D4169 performance testing of shipping containers and systems 3 is a schedule-based practice you can tune to your distribution cycle.

- ASTM D5276 drop test of loaded containers by free fall 4 is a common method to standardize drops on loaded cases.

- ASTM D642 compression testing of shipping containers 5 supports stacking and warehouse compression validation.

- ASTM D4728 random vibration testing of filled shipping units 6 helps quantify vibration risk with representative vibration inputs.

ASTM is useful when you want a plan that mirrors your real hazard sequence, with defined levels.

| Shipping scenario | Good starting procedure | What it stresses | What to watch in results |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTC parcel (single case) | ISTA 3A | drops + vibration | neck breaks, heel chips, divider failure |

| Palletized full truckload | ISTA 3E | vibration + compression + shock | pallet lean, corner crush, scuffing |

| Mixed freight / LTL | ASTM D4169 (selected cycle) | handling + stacking + vibration | carton collapse, product movement |

| Export with humidity | ISTA/ASTM + conditioning | moisture + compression loss | softened boxes, strap cut-in |

| Lightweight bottles | same test, tighter criteria | scuffs and delayed cracks | micro-damage patterns after test |

Define pass and fail in a way that matches business risk

A test without criteria is only a video. Pass and fail should include:

- zero broken bottles in the sample, or a defined maximum,

- no glass-to-glass contact marks,

- carton integrity limits (no corner collapse beyond a limit),

- stable pallet geometry (no lean beyond a limit),

- closure integrity if you ship filled product.

The best approach is to test the final pack-out, not a simplified lab version. Use real pallets, real wrap, real cartons, and the real bottle coating condition. That is the only way to predict claims.

Conclusion

Transport breakage drops when bottles never touch each other, pallets never shear, and cartons keep compression strength. Build one lane-specific pack-out, then validate it with ISTA or ASTM simulations.

Footnotes

-

Shows what ISTA 3A covers for parcel hazards like drops and vibration on individual packages. ↩︎ ↩

-

Summarizes ISTA 3E for unitized pallet loads in full-truckload distribution environments. ↩︎ ↩

-

Explains ASTM D4169’s schedule-based approach to simulate real distribution cycles and hazard sequences. ↩︎ ↩

-

Defines a consistent free-fall drop method for loaded cases, useful for comparing pack-out changes. ↩︎ ↩

-

Covers compression testing to validate stacking strength and reduce bottom-layer crush failures. ↩︎ ↩

-

Details random vibration testing concepts to evaluate how vibration drives rub damage and fatigue. ↩︎ ↩