Choosing a food jar looks simple until lids leak, labels wrinkle, or glass breaks in hot-fill. The right choice starts before any sauce hits the line.

You choose the right food jar by matching closure and liner to the recipe, jar shape to scooping or pouring, design to thermal process, and glass color to light sensitivity and brand.

In real projects, the jar is part of the product. It must protect flavor, survive filling and logistics, and still look good in the customer’s fridge or pantry months later. Let’s break the decisions into closures, shapes, heat treatment, and color.

Which closures—lug, twist, clip-top—ensure airtight, leak-proof seals?

A beautiful jar does not help if the cap fails and the product ferments, leaks, or rusts on the shelf.

Lug, twist-off, clip-top, and continuous-thread closures can all be airtight, but they must match the jar finish, product chemistry, and process method to hold vacuum and prevent leaks.

How main closure types actually seal

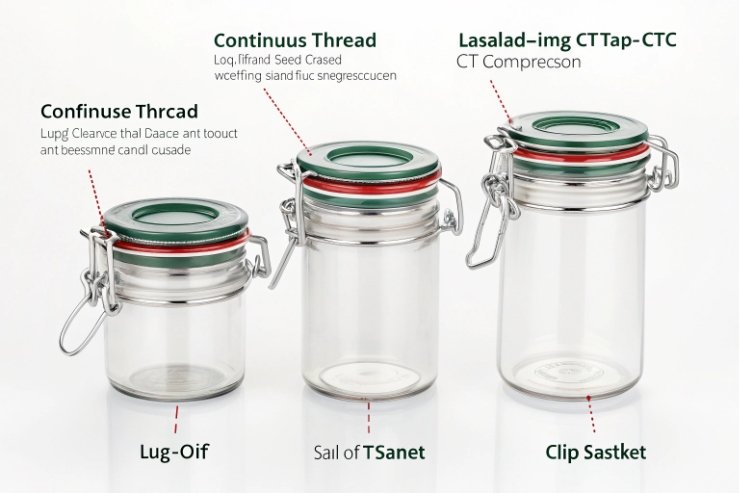

For most commercial food jars, three closure families keep showing up: lug (twist-off), continuous-thread (CT), and mechanical clip-top with gasket. Before choosing any of them, it helps to confirm jar neck finish and thread dimensions 1 so the cap and glass finish truly match.

Lug or twist-off lids sit on jars with matching “twist” finishes. The cap has interrupted lugs that grip under small glass ramps on the finish. During hot-fill or pasteurization, the product cools, a vacuum forms, and the lid pulls tight onto the sealing compound. This style is standard for jams, pickles, sauces, and many spreads, and the seal logic is well explained in metal lug closures 2. It is fast on automated lines and gives clear “button click” tamper evidence.

Continuous-thread closures screw all the way around. Think of classic mason-style jars and many dry-food jars. In food industry, CT closures often use liners like plastisol, pulp/poly, or F217 to create the seal on the glass land. A clear definition of how this differs from lug finishes is covered in continuous-thread closures 3. They work well for dry goods, nut butters, and ambient sauces that do not need high vacuum. With the right liner, they can also handle hot-fill.

Clip-top jars use a glass body with a separate glass or plastic lid, plus a silicone or rubber gasket and metal clips. When you push the clip down, the gasket compresses and creates an airtight seal. These jars feel very “home-made” and work well for short-shelf products, chilled items, and refills. They are less common on high-speed fully automated lines but very popular in premium segments and reusable systems.

For true canning (home or small-batch water-bath/pressure canning), two-piece lids are still common: a flat disc with sealing compound and a separate screw band. The disc seals to the glass under heat and vacuum; the band just holds it during processing.

| Closure type | Typical jar finish | Best for | Key strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lug / twist-off | Lug / twist finish | Jams, pickles, sauces, spreads | Strong vacuum seal, fast on lines |

| Continuous-thread | CT finish (e.g. 70-400) | Dry goods, nut butters, hot-fill jars | Simple, flexible liner options |

| Clip-top | Wire bail finish | Refills, gifts, short-shelf products | Reusable feel, strong brand story |

| Two-piece lid | Mason / CT canning | Water-bath or pressure canning | Proven vacuum canning performance |

Matching liners and closures to real recipes

The closure is not just metal or plastic. The liner or gasket inside does most of the sealing work. Acidic tomato sauces, hot chili, high-salt pickles, and oil-rich spreads all stress the liner differently.

Acidic products like pickles, salsa, and many fruit jams do well with food-grade compound liners in lug or disc lids. If your spec calls for that classic vacuum “pop,” it’s worth reviewing how plastisol liners work in jar closures 4. For long shelf life, oxygen-barrier compounds help slow oxidation. For very oily or high-salt products, we pay extra attention to liner resistance to swelling and corrosion.

Nut butters and chocolate spreads often use CT lids with F217 or pulp/poly liners. These liners give a good seal and handle oil on the rim. They also avoid strong plastic smell, which is important because these products sit close to the lid for months.

Clip-top jars depend on gasket quality. Silicone gaskets hold shape and seal better over repeated use and washing. Natural rubber feels traditional but may harden faster and has more odor risk with sensitive foods.

In our projects, the safest path is to choose jar finish and closure family first, then run real product tests with the planned liner or gasket. Only when the combination survives heat, storage, and transport without leaks or rust do we lock the spec.

What jar shapes suit sauces, spreads, and dry goods for scooping?

The wrong jar shape turns simple breakfast into a wrestling match with the spoon. Good shapes follow how people scoop, pour, and store.

Round, straight-sided, and wide-mouth jars work best for sauces and spreads, while tall or square jars suit pourable or dry goods. Scooping needs wide openings and simple internal geometry.

Match jar body and mouth to the way people use the product

For spreads like peanut butter, chocolate cream, tahini, or honey, wide-mouth jars are almost always best. Mouth diameters from about 63 mm upward let a spoon or knife reach the bottom and corners. Straight sides make it easier to scrape out the last 10% so customers do not feel waste.

Sauces sit between pouring and scooping. Smooth pasta sauces that people pour into a pan can use narrower necks, but the jar still needs a hand-friendly shape and enough access for cleaning if it is reusable. Chunky sauces or relishes, with visible pieces of vegetables or fruit, benefit from wider mouths so pieces do not block the opening.

Dry goods such as grains, nuts, sweets, or coffee beans behave differently. They pour more easily. Here, taller jars or square/rectangular jars can use shelf space more efficiently. Square jars pack tightly in cases and create clean label panels on each face. They also stack well in pantries.

For foodservice, jar shape also affects scooping with larger utensils. Straight-sided gallon or liter jars with wide mouths allow ladles and large spoons, and they stack neatly in fridges. Hand grip is important too. Gentle “waist” curves or shoulder grips make heavy jars safer to handle with wet hands.

| Product type | Ideal mouth | Body shape | User benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nut butters | Wide-mouth | Straight-sided round | Easy knife access and scraping |

| Chocolate spreads | Wide-mouth | Low, squat glass jar | Stable on table, premium feel |

| Chunky sauces | Medium to wide-mouth | Round or slight hex | Spoon access, less clogging |

| Smooth sauces | Regular / medium | Round, taller profile | Better pouring, neat portioning |

| Dry goods | Medium / wide | Square or rectangular | Space-efficient, strong label area |

Think about labeling, line performance, and home storage

Shape is not only for the consumer. It also must run well on filling, capping, labeling, and packing lines.

Straight-sided jars label more cleanly. Automated labelers like constant curvature and simple walls. Complex shoulders, deep embossing, or sharp tapers near the label area create wrinkles and bubbles, especially with paper labels. When a client wants heavy decoration, we often move embossing to the shoulder or heel and keep a “quiet zone” for the label.

On the line, jars should be stable on conveyors. A very tall, narrow jar with a tiny base may tip at high line speeds. A slightly wider base or lower center of gravity, even at the same volume, can reduce downtime and glass breakage.

At home, jar diameter decides if it fits on fridge doors or standard shelves. Very wide jars may look premium but push customers to move things around each time. Simple proportions that match common fridge and pantry spacing make the product easier to live with. That comfort turns into repeat purchases.

When we design a new jar, we often start from three simple questions: will the customer pour or scoop, how will they store it, and where will the label sit without trouble. The answers guide shape much more than pure “style” references.

Do hot-fill/retort needs drive ΔT and vacuum panel specs?

A jar that survives cold chain may crack in a retort. Thermal process decides how much stress the glass sees.

Yes. Hot-fill and retort conditions set the glass ΔT limits, wall profile, and vacuum panel design. The jar must handle heat, cooling, pressure, and vacuum without breaking or paneling too hard.

Understand your process before you choose a jar

Every food project should start with the thermal story. Is the product ambient, pasteurized, hot-filled, or retorted?

Ambient fill with no pasteurization puts the least stress on glass. Jars mostly see room temperature and mild cooling. Standard container glass is fine, as long as the closure seals and the product is stable by formulation.

Hot-fill means product enters the jar at around 80–95°C, sometimes higher, then the jar may be inverted and cooled. This creates internal pressure at first, then vacuum as the headspace contracts on cooling. The glass must withstand both the high product temperature and the ΔT between hot inside and cooler outside.

Retort or pressure canning brings the highest demands. Jars go into a retort at up to 121°C with pressurized steam or water, then they cool down in a controlled way. A straightforward overview of retort processing temperatures and pressure ranges 5 helps teams align packaging, QA, and process engineering on the same assumptions.

If we do not match jar design and glass recipe to this process, problems show up as heel checks (cracks at the bottom edge), shoulder cracks, or sudden breakage when jars come out of the retort or hot water.

What ΔT and vacuum design mean in practice

ΔT is the maximum temperature difference the glass can handle between inside and outside. Hot-fill jars are designed for higher ΔT than simple table jars. They often have thicker walls in critical zones and smoother transitions at the shoulder and heel. This spreads thermal and mechanical stress.

Vacuum panels are slight indents or panels in the jar body that can move in under vacuum. Without them, as the product cools, negative pressure may deform the lid excessively or put too much load on the shoulder. With panels, some of that force is absorbed by a small “breathing” of the side walls. On straight jars, we sometimes use subtle vertical ribs instead.

Retort-capable jars need extra safety margin. Glass distribution must be very tight. We avoid sharp embossing in stress areas. We also coordinate with the filling line on pre-heating and cooling stages, so spray patterns and water temperatures stay within modeled limits. Even the conveyor layout through the retort and cooler can matter.

One risk buyers sometimes underestimate is cooling shock. The FDA specifically warns that thermal shock during retort cooling can break glass containers 6 if cooling is too severe or uneven.

Here is how process choice influences jar spec:

| Process | Typical temperature range | Jar design focus |

|---|---|---|

| Ambient / cold-fill | 10–30°C | Standard glass, normal walls |

| Hot-fill | ~80–95°C | Higher ΔT glass, smooth shoulders, vacuum panels, tested closures |

| Pasteurization | 60–90°C | Similar to hot-fill, but check for longer time in heat |

| Retort | Up to 121°C + pressure | Heavy-duty glass, strict ΔT control, smooth geometry |

Once the process is fixed, the jar design needs to be tested under worst-case conditions with real product. Simulation helps, but real runs catch surprises like uneven heating, cold water spots, or unexpected vacuum levels. Only after that do we freeze the specification.

Which glass colors protect light-sensitive ingredients?

Light can fade herbs, oxidize oils, and dull bright sauces long before the “best before” date on the label.

Amber and dark green glass protect light-sensitive ingredients far better than clear flint. Coatings and tints add extra UV defense while supporting brand colors and shelf impact.

Match color to how sensitive the recipe is

Some foods hardly notice light. Others change fast. Oils, herbs, spices, teas, coffee, and many natural colorants are especially sensitive. UV and blue light can break down pigments and flavors, leading to taste loss, rancidity, or color changes.

Clear flint glass shows the product perfectly but gives the least UV protection. If the product sits only in cartons or shaded shelves, this may be enough. Many jams and pickles live happily in clear glass because their main risks are more about oxygen and heat than light.

Amber glass is the workhorse for light-sensitive foods. If your team needs a simple explanation for why, the science behind amber glass UV protection 7 is a useful reference. For herb oils, infused oils, and some probiotic or ferment products, amber jars can significantly slow degradation.

Dark green glass offers moderate to good light protection, more than flint but usually a bit less than amber in the UV bands. It also carries a strong natural and traditional signal. For some brands, green jars balance protection and look, especially for herbs, teas, and pickled vegetables.

Coated and painted glass can add even more control. A full-body opaque coating on a flint jar blocks most light regardless of base color, as long as the coating is continuous and uses suitable pigments. Frosted or matte coatings diffuse light but do not fully block UV, so they give a softer look rather than complete protection.

| Glass type | UV protection level | Best suited for |

|---|---|---|

| Clear flint | Low | Jams, pickles, short-shelf chilled products |

| Light tint | Low to medium | Everyday sauces where color display matters |

| Dark green | Medium to high | Herbs, teas, pickles with some light sensitivity |

| Amber | High | Oils, herb extracts, probiotics, sensitive colors |

| Opaque coated | Very high | Premium lines, strong natural or clean branding |

Use color to tell the brand story and support sustainability

Color is also part of marketing. Clear glass says “nothing to hide”. Customers see texture, fruit pieces, or layers. This works well for vibrant jams, pickled vegetables, and colorful sauces. When the recipe is stable enough, this transparency supports trust.

Amber and green link strongly to “natural”, “organic”, and “traditional” in many markets. They also allow higher mixed-color cullet use in the furnace, which supports higher recycled content. For brands with an eco story, using amber jars with clear claims about recycled content can connect packaging and message.

Coatings let you keep the technical benefits of amber or green while meeting a brand color palette. For example, an amber jar under a white or pastel coating still benefits from the inner color. This way, shelf life and design do not fight each other.

In many cases, we design two levels: a clear line for basic, fast-rotating SKUs and an amber or coated line for higher-value or more sensitive recipes. This gives a clear visual step-up and keeps the technical protection where it is most needed.

Conclusion

The right food jar is a careful match between recipe, process, closure, shape, and glass color, so the product stays safe, easy to use, and strong on the shelf.

Footnotes

-

Quick guide to finish/thread sizing so jar and cap match before tooling or purchase. ↩︎ ↩

-

How lug caps use sealing compound and vacuum to create hermetic seals on food jars. ↩︎ ↩

-

Clear definition of continuous-thread closures and why CT differs from lug finishes. ↩︎ ↩

-

Practical overview of plastisol liners and why they’re common for vacuum-sealed glass food jars. ↩︎ ↩

-

Explains hot-fill vs retort and typical retort temperatures and pressure for shelf-stable foods. ↩︎ ↩

-

FDA notes how thermal shock during retort cooling can break glass and why controlled cooling matters. ↩︎ ↩

-

Shows how amber glass blocks UV and helps protect light-sensitive products from oxidation and degradation. ↩︎ ↩